This is the fourth in a series of four blog posts concerning post-Civil War Virginia and the lives of freedpeople after Emancipation. The posts precede the Library of Virginia exhibition Remaking Virginia: Transformation through Emancipation opening 6 July 2015.

With the Civil War ended and slavery abolished, many African Americans believed that freedom should be much more than an absence of slavery. They believed it should include full rights and responsibilities of citizenship, including rights to personal liberty, property ownership, and participation in public life by voting and holding office. In the spring of 1865, African American men in Norfolk organized the Colored Monitor Union Club to demand full rights of citizenship, including the right to vote. “Give us the suffrage,” they asserted in an address published as Equal Suffrage: An Appeal from the Colored Citizens of Norfolk, Va., to the People of the United States (1865), “and you may rely upon us to secure justice for ourselves.” In Hampton, Richmond, and other communities, African American men organized political clubs for the same purpose. Most white Virginians opposed granting freedmen the right to vote.

By the end of 1865, Radical Republicans in Congress had become frustrated with the opposition of many white southerners to extending full rights of citizenship to African Americans. During the next three years Congress adopted a series of Reconstruction and civil rights laws imposing reforms on the Southern states. Early in 1867 Congress passed an act placing the Southern states under military rule and requiring them to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment and to write new constitutions before they could be readmitted to the Union.

Virginia became the First Military District, and its military commander called for a referendum on whether to have a convention to rewrite the constitution and an election to choose members. During the weeks preceding the election, African Americans held conventions across the state to organize politically and to nominate candidates for the convention. On 22 October 1867, African American men voted in Virginia for the first time. When they arrived at the polling place, their votes were tabulated on lists separate from white voters and in some or all of the counties they had to place their ballots in separate boxes.

Ballot Box used in 1867 election.

King George County Court Records, 1800-1909, Local Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia.

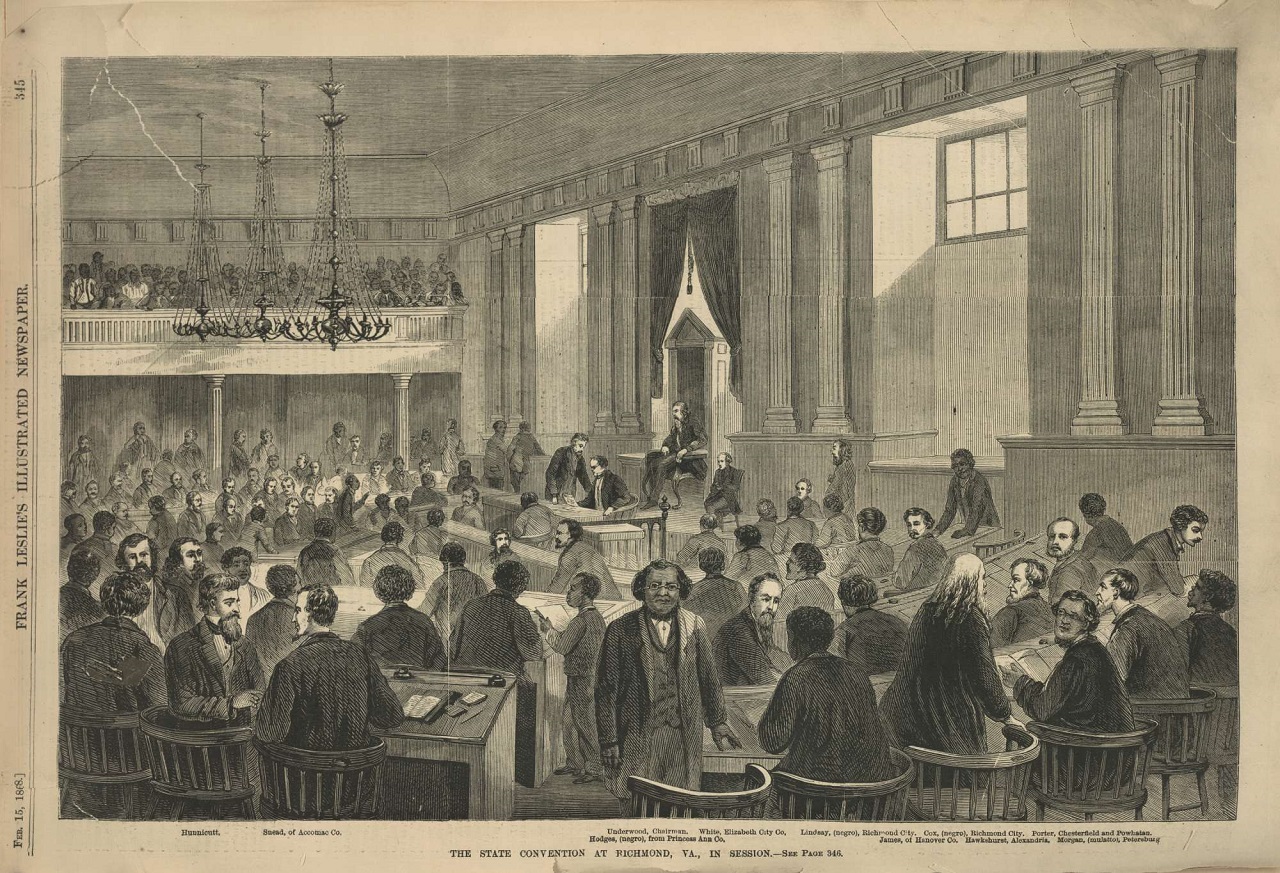

Twenty-four African Americans won election to the convention, becoming the first black Virginians to hold public office. Some had been free before the war, but many had become free as a consequence of the war. Among them was John Brown (ca. 1830–ca. 1900) who had lived in slavery in Southampton County and emerged as a leader of the freedpeople after the war. With his campaign slogan “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself” printed on the ballots he distributed to men who voted for him, he defeated two white candidates to win election to the convention.

The convention met in Richmond from 3 December 1867 to 17 April 1868, adopting a constitution that reformed local government, required the General Assembly to create a statewide system of free public schools for all children, and granted the vote to African American men. Some supporters of the Confederacy were initially disfranchised by the constitution, but voters rejected those disfranchisement clauses when the constitution was ratified on 6 July 1869.

Reconstruction under federal government supervision lasted in Virginia until January 1870, but reconstructing the Union and constructing a new Virginia were processes that lasted beyond the official end of military government. This long period was a time of difficult adjustments as well as significant accomplishments as Virginians of all backgrounds attempted to rebuild in the radically new conditions that the defeat of the Confederacy and the abolition of slavery produced.

Between the election of members to the Constitutional Convention in October 1867 and the end of the General Assembly session of 1889–1891, nearly a hundred African American men won election to the Convention, the House of Delegates, and the Senate of Virginia. Many white Virginians continued to oppose African American suffrage, and the General Assembly passed legislation in the 1870s and 1880s to limit the number of black voters. A new state constitution in 1902 authorized the General Assembly to further revise voting and registration laws, depriving most African Americans of the right to vote and to hold public office.

Election records documenting African American voting in Virginia can be found in state and local records at the Library of Virginia, including Secretary of the Commonwealth General Election Records (1867, 1869), Accession 50706, State Government Records Collection, and surviving poll books in some county records.

–Marianne E. Julienne, an editor of the Dictionary of Virginia Biography

–Brent Tarter, a founding editor of the Dictionary of Virginia Biography.

Header Image Citation

The State Convention at Richmond, Va., In Session, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, February 15, 1868, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.