Life for African Americans in Virginia following the end of the Civil War can be described as uncertain at best. As the social balance between white and black Virginians was virtually turned on its head, Virginia’s African American population expected to be governed by the same system of law and order as their white neighbors. Unfortunately, this was usually not the case, and stories of mob violence directed towards African Americans permeate the historical record immediately following Emancipation. These stories are being uncovered daily by the Library of Virginia’s African American Narrative project and made public by the Library’s new exhibit, Remaking Virginia: Transformation Through Emancipation. These acts often erupted out of allegations of crimes committed by African Americans and usually ended in an illegal execution of the alleged criminals, bypassing the standard presumption of “innocent until proven guilty.”

Two instances of such violence were recently discovered in the Library’s collection of Coroners’ Inquisitions. Coroners’ inquisitions are investigations into the deaths of individuals who died in a sudden, violent, unnatural or suspicious manner, or died without medical attendance. They are a revealing and sometimes gruesome source of historical information. In Accomack County, sometime in early April 1866, a coroner and his jury were sent to examine the body of an African American man found hanging from a tree. He was named James Holden, but little other information is given except that he “came to his death hanging by the neck by some person or persons unknown.” However, in the same collection is an inquisition held over the body of a Mrs. John Drummond, who was found bludgeoned with an axe during an attempted robbery a few days prior to the discovery of Holden’s body. The inquisition includes a deposition from an eyewitness who explicitly named John Holden as the murderer of Mrs. Drummond, and mentions that Holden had already “been arrested and confined in Pungoteague.” There is no mention of what happened in the time between his arrest and the discovery of his body. For that we must turn to the newspapers.

Click image to view full-size.

Accomack County (Va.) Circuit Court Records. Local Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

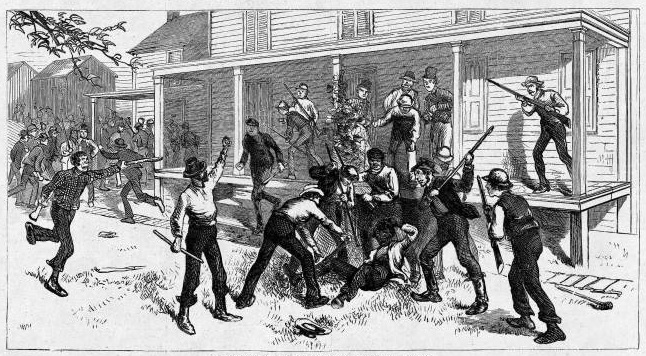

A story titled “Murder and Lynch Law In Accomac County” was published in the Staunton Spectator on 1 May 1866, roughly two weeks after the two Coroners’ Inquisitions. The story fills in the gaps, mentioning Mrs. Drummond’s brutal murder at the hands of “a negro” and the “Citizens of Pungoteague” who “went in search of the author of the fiendish act, and capturing him, at once hung him to the limb of a tree.”

Click image to view full-size.

Warren County (Va.) Circuit Court Records. Local Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

The Warren County Coroners’ Inquisitions contains a similar occurrence from three years later. An inquisition dated 20 August 1869 notes the discovery of two bodies belonging to African American males found “hung to a tree” in Front Royal. This time we are given some insight as to what happened in the actual inquisition. The coroner noted that the “jail of Warren County was forcibly entered by six men in disguise” who removed two prisoners, Charles Brown and Jacob Berryman. They were carried away and lynched by the disguised men. Little information is given regarding the arrest of Brown and Berryman so again we go to the press! The Staunton Spectator and Evening Star both mention the incident but the Alexandria Gazette gives us the most detailed account of what happened. According to the Gazette, Brown and Berryman were arrested for assaulting a young girl named Alice Thompson.

Little detail is given regarding the assault except that she was hit and choked by Brown after being pursued into some thick woods. Once word got around that two African American men had allegedly assaulted a young white woman, “the narration of this incident occasioned the most intense excitement” and “threats of lynching the criminals were so current in the neighborhood that the jail, for some days and nights, was guarded by a strong force of armed men.” This protection wouldn’t last long, and the Gazette notes that “those they had protected probably met an awful fate.”

These examples illustrate the fragile existence of newly freed African Americans in Virginia. Although in both cases individuals were accused of pretty heinous acts of violence, the community’s outrage overrode a judicial system that was established to protect the rights of the accused until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Furthermore, these narratives were constructed by the use of multiple sets of records housed in the Library. The Coroners’ Inquisitions only give us half of the story, while the newspapers help us as archivists and researchers to fill in the gaps and can point us in the direction of other materials that expose even more information. Pulled together, the multiple records help to tell the story of the realities of life for African Americans in the period following the Civil War.

–Chris Smith, Archival Assistant

Note: The author would like to recognize and thank Mary Dean Carter and Ed Jordan for their assistance with the development of this post.

The Library’s current exhibit Remaking Virginia: Transformation Through Emancipation is open to the public Monday through Saturday, 9:00am to 5:00pm until March 26th, 2016.