Given the current coronavirus health crisis, processing a small collection of Chesterfield County smallpox epidemic records from the 19th century seemed to be a timely project as there is much to be learned about people and communities in times of crisis. Chesterfield County experienced two smallpox outbreaks in the 1800s: one in 1829, which was of relatively short duration, and another lengthier and deadlier one seven years later, beginning in 1836 and winding down by spring 1837.

Rumors of smallpox cases were typically brought before a locality’s justices of the peace, who then determined the merit of the rumors and made decisions about next steps. On 7 March 1829, a group of justices met at Haley Cole’s tavern in Chesterfield and determined that an outbreak of smallpox in the area existed “to the manifest danger of the health and lives of the inhabitants of the said county.”

According to the meeting minutes, the justices approved the establishment of a makeshift hospital at the home of Mr. Frances Watkins. They appointed a physician and manager, and outlined their duties and expectations, including directing the physician to “keep an exact account of services rendered to hospital patients, charging the lowest rate of such services…if able (to) the master or mistress of any slave, or slaves.” They also made this plea to the public: “It is earnestly recommended to all heads of families and all the good people of this county at once to have recourse to universal vaccination as the most speedy & effectual mode of preventing the farther progress of this infectious and dangerous disease.” Ten days later, the justices estimated about 30 confirmed cases, but fortunately reported no deaths. By mid-April the outbreak had subsided, and they permitted the physician to close the hospital when the last patients were released.

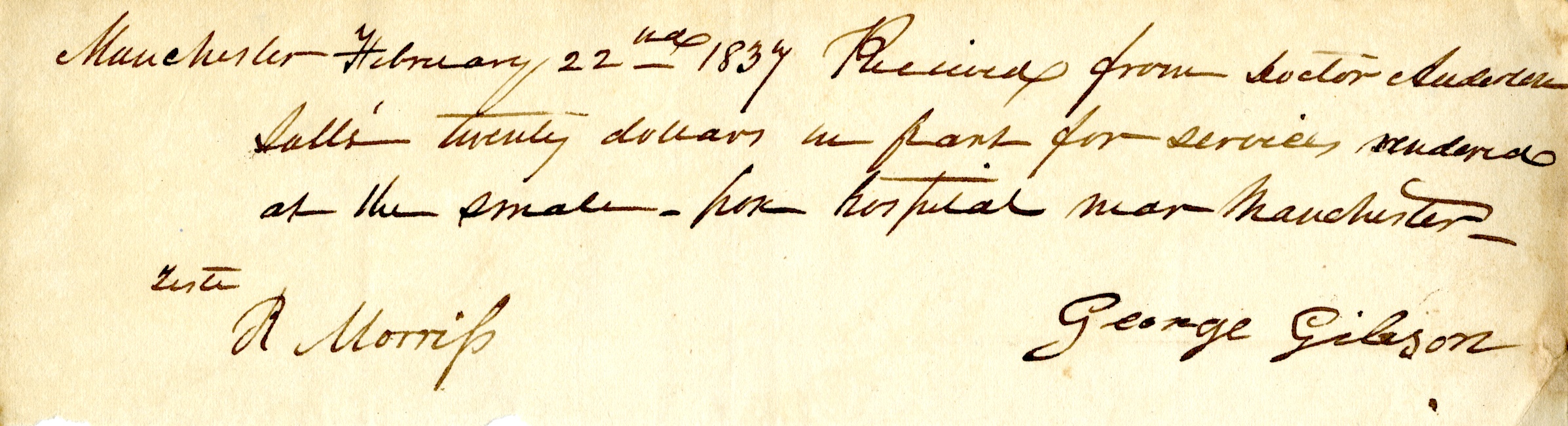

The next outbreak was lengthier. An order from March 1837 indicates that a smallpox outbreak began the previous summer, as it references “claims against the county in relation to the Small pox hospital established near the town of Manchester…of the 21st July 1836.” However, there is no documentation prior to November to corroborate this. Dr. Anderson Salle, the appointed physician, kept receipts and documented most debts and expenditures in detail. Invoices and receipts regarding supplies, food, use of horses and carts for transporting patients to the hospital, and other nursing and medical assistance date from 1 November 1836 through mid-April 1837.

-

Order entered 16 March 1837, referencing claims of a possible outbreak of smallpox in Chesterfield County at that time and establishing a hospital in Manchester.

-

November 1836 receipt of payment to R.R. Morgan for his services “conveying Person to the hospitles With the small pox and two days for horse hire.”

-

November 1836 receipt showing various supplies sold to the smallpox hospital for Chesterfield County.

At the close of the outbreak, county commissioners used many of Dr. Salle’s figures in their report of claims and accounts to be paid by the county. Aside from paying Dr. Salle, his manager, and suppliers of goods, the report also included five nurses to be paid, all of whom were free persons of color: Henry Jackson, George Gibson, Caty (or Katy) Cheatham, Kitty Green, and Lucretia Brown. Not surprisingly, they were all underpaid for the risks associated with the job, as the cost of a hospital stay for a free African American was roughly one dollar, and the men earned more per day than the women ($1.25 vs. $0.50). Lucretia had worked for 35 days before becoming ill herself and being hospitalized for 17 days. As a result, she only received 50 cents for her work. According to vouchers and receipts, it appears that Dr. Salle used some of his personal funds to provide a degree of relief to George, Henry, and Caty (Katy), perhaps because those three had shown such significant dedication by working at the hospital for over 100 days each.

Given the legal status of free African Americans during that period, it seemed possible that any of those five individuals may have petitioned the county for permission to remain in the Commonwealth at some point, and that other documents relating to their freedom might be available digitally in Virginia Untold. A cursory search for those five names (six if you include the Caty/Katy spelling variations) yielded one result. A “Katy Cheatham” living in Manchester petitioned the Chesterfield County Court in 1838, and in 1840 received permission to remain “by reason of her good character and many good qualities universally respected by her acquaintances; she has been of great service occasionally in this place, and its vicinity, in nursing the sick, especially during the time that the small pox last prevailed in this town and neighbourhood.” (Click here to read the transcript). Another quick search in Virginia Untold also yielded her potential “free negro registration” in June 1840, which provided additional information: “Katy Cheatham – stature 5 feet 2 ½ inches – color mulatto – age 40 years – a mole on the right side of the face & one near the mouth – emancipated by deed from Wm. Kerr.”

-

1837 commissioners’ report showing funds due to the county from individuals expected to pay for their enslaved people for “the support, nursing and medical attention furnished their slaves while confined in the Hospital.”

-

Page 1 of Dr. Salle’s report of patients admitted to the smallpox hospital in Manchester. This is perhaps the most informative document in the collection. It is a nearly 3-foot long handwritten list of all people admitted, by date of admission, whether enslaved, free, or white, number of days hospitalized, and death date if applicable.

-

Page 2 of Dr. Salle’s report of patients admitted to the smallpox hospital in Manchester.

The commissioners’ report in the smallpox collection also included a list for payments due the county from owners of enslaved people for “the support, nursing and medical attention furnished their slaves while confined in the Hospital.” This documented the names of the enslaved people, number of days hospitalized, and whether they survived (if there was no charge for coffin and grave). Since people who were considered “paupers” could not pay, and thus were not chargeable, they were not on the list. The commissioners acknowledged that Dr. Salle’s report was much more exhaustive, as it listed every person admitted to the hospital.

Dr. Salle’s report is perhaps the most informative document in the collection. It is a nearly 3-foot long handwritten list of all people admitted, organized by date of admission, including whether they were enslaved, free, or white, number of days hospitalized, and death date if applicable. First patient: “1836, Nov. 15th, George, a negro man hired by Wm. P. Strother, but belonging to old Mrs. Davidson…and died on the 24th of the same month.” Last patient: “April 6 [1837]-Mary Henley free woman of colour admitted and discharged April 21st.” As with Caty Cheatham, many of the names in this list could be further searchable in Virginia Untold, as well as in various deed books, order books, or tax books.

The smallpox epidemic appeared to have ended by summer 1837, but an observation by Dr. Salle prompted him to write the commissioners with a special request in October. He noticed that “when the small-pox hospital near this place was closed, the blankets, beds, & c. were left in the house and the doors locked.” However, the house had since been opened, either by curious persons, or those seeking to steal what had been left within. He cautioned that this “may be the means of the disease appearing again somewhere in the county… Does it not appear obviously proper that the house should undergo a thorough cleansing by white washing and scouring it & burning beds, etc.? Such is my view of the matter.”

He further stated that this should be done at the expense of the county, since the county had used the property with no payment to any owner. He also expected the county to pay workers well to do it, as “it is a job which very few can be found to undertake, and those who would must have triple pay.” The last item in the collection is thus the 13 November 1837 court order (recorded the following February) to do so, under the direction of Dr. Salle. The order noted that the county paid free African American and former smallpox nurse Henry Jackson ten dollars for this service.

The Chesterfield County Smallpox Epidemic Records were processed with other Chesterfield County Health and Medical Records as the Chesterfield County (Va.) Health and Medical Records, 1780-1904. Researchers may find other available collections of Smallpox Epidemic Records in Local Records collections by going to the advanced search page in Virginia Heritage for collections at the Library of Virginia with “smallpox” in the title, or with “smallpox” in the word/phrase field. Other health and medical collections in Local Records collections will continue to be processed in the future.

–Tracy Harter, Sr. Local Records Consulting Archivist