In the fall semester of 2019, which seems like years ago these days, I was lucky enough to wrap up my MLIS program with an internship through The University of Alabama. UA linked up with WGBH and AAPB (American Archives of Public Broadcasting) to create a unique digitization prospect.

My job here at the LVA consists of digitizing static material. This includes paintings, blueprints, broadsides, bibles, private papers, special collection items, and maps, to name a few. When the opportunity occurred to participate in digitizing moving images, let’s just say I was very interested. I was paired up with our local public broadcast station, VPM (Virginia’s home for Public Media), to assist them in digitizing some of their content.

Coming into this program I thought I had a good grasp on digitization, but moving image is a different beast. After a week of immersion training in Tuscaloosa with the fine folks at WGBH & AAPB, Rebecca Fraimow, Miranda Villesvik and Casey Davis Kaufman, along with Audiovisual Archivist and Educator Jackie Jay, we were sent on our way.

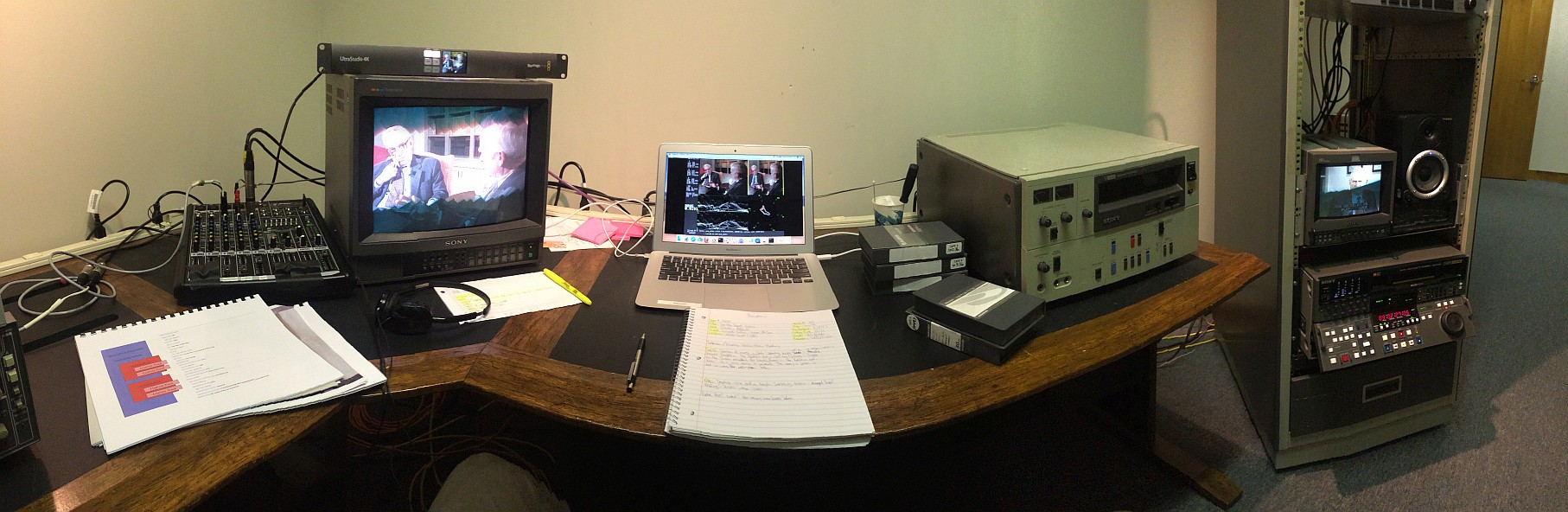

We had several requirements that AAPB requested of us, the bulk of which was to digitize 30-60 hours of broadcast tapes at VPM. The workstation we used is a combination of a DigiBeta deck to play back the tapes, a laptop and a capture card along with two monitors and a sound mixing board. We used Vrecord capture video and turn it into a digital file. This required us to watch the tapes in real time and record metadata to be ingested into the AAPB AMS (Archival Management System), ensuring future accessibility and retrieval. I jotted down copious notes as the tapes were playing then transferred the metadata to spreadsheets for ingest. We were tasked with ingesting the metadata into the AMS. This requires us to format a spreadsheet to specific requirements and take the necessary steps to create a special collection in the AMS. I ran MD5 checksums on all the files, both master and proxy. This is a digital fingerprint that ensures files have not been tampered with during shipment. When AAPB and VPM receive the files, they will run the checksums again, comparing it with the ones I provided.

VPM decided on the content for our collection. It mainly focused on Virginia politics, policy and public affairs. For the Record and From Our Archives made up the bulk of the tapes. These were interviews focusing on different local politicians and notable people. Additionally, the station requested a dozen or so individual episodes and miniseries to be digitized. Among these was a four-part miniseries recorded in the early 1990’s about Virginia’s land usage, titled Highest and Best. It focused on suburban sprawl, land density, and the cyclical motion of people moving back to the city from the suburbs. This concept resonates still to this day and it was interesting to see their take on it almost 30 years ago. In total, I was able to digitize 57 tapes adding up to 36 hours of content to the AAPB.

The digitization process was relativity smooth going. I did have to pull apart the DigiBeta deck to manually clean the heads and rollers because it had gotten dirty enough to distort the program I had been capturing. This was both exciting and terrifying. Luckily, I found a great tutorial online that took me through step by step to rectify the problem. Afterwards I realized that I could have used a head cleaning tape instead of pulling the deck apart. But I was able to get it back together and working so, there you go. It’s all about the process.

Digitization is very slow going, it takes time to watch the tapes, record metadata and make sure there are no discrepancies in the playback. This was my main takeaway of the program. There are many things that can go wrong during the multistep digitization process. The need to back up all the material that is digitized is tantamount. Jackie Jay stressed this in training, backup your backups. I experienced this first hand in the last few months. I’m currently dealing with a hard drive that is giving me problems. It is a lot of work that can potentially be lost without that second failsafe. That being said, this tedious practice needs to be implemented sooner than later. When I initially started the internship, I didn’t understand how quickly media playback decks are becoming extinct. There is a shelf life for the tapes and in the right conditions they can last awhile. These machines are not being made anymore, finding one that works is becoming increasingly difficult. I am walking away from this experience focused on preservation and access, with the understanding of the limited time we have to capture aging technology.

I want to say thanks to the people at WGBH and AAPB, Rebecca Fraimow, Miranda Villesvik and Casey Davis Kaufman and Jackie Jay. These four human beings have a wealth of amazing knowledge between them. They were very helpful with this whole process. Thanks to VPM and UA for the opportunity, I won’t forget it.

-Ben Steck, Digital & Video Imaging Specialist