The “Runaway Slaves” Records, 1791-1863, available at Virginia Untold: the African American Narrative, include reports, accounts, correspondence, court records, and receipts concerning expenses incurred by localities related to the capture and sale of people attempting to escape enslavement. These records contain the stories of enslaved people who risked everything, not least of all their lives, to emancipate themselves. They also reveal a lesser-known history, namely how local and state governments financially benefitted from the sale of enslaved people.

The human trafficking economy known as the slave trade relied largely on private financial transactions. Individuals sold human beings to each other as one might sell a used car to another person via Craigslist today. Wholesale concerns, such as those of Moses Austin & Company, Franklin & Armfield, and Silas Omohundro, auctioned larger groups of enslaved men and women to individuals or businesses from their auction houses or store fronts. However, the overall system of slavery generated other avenues of money-making.

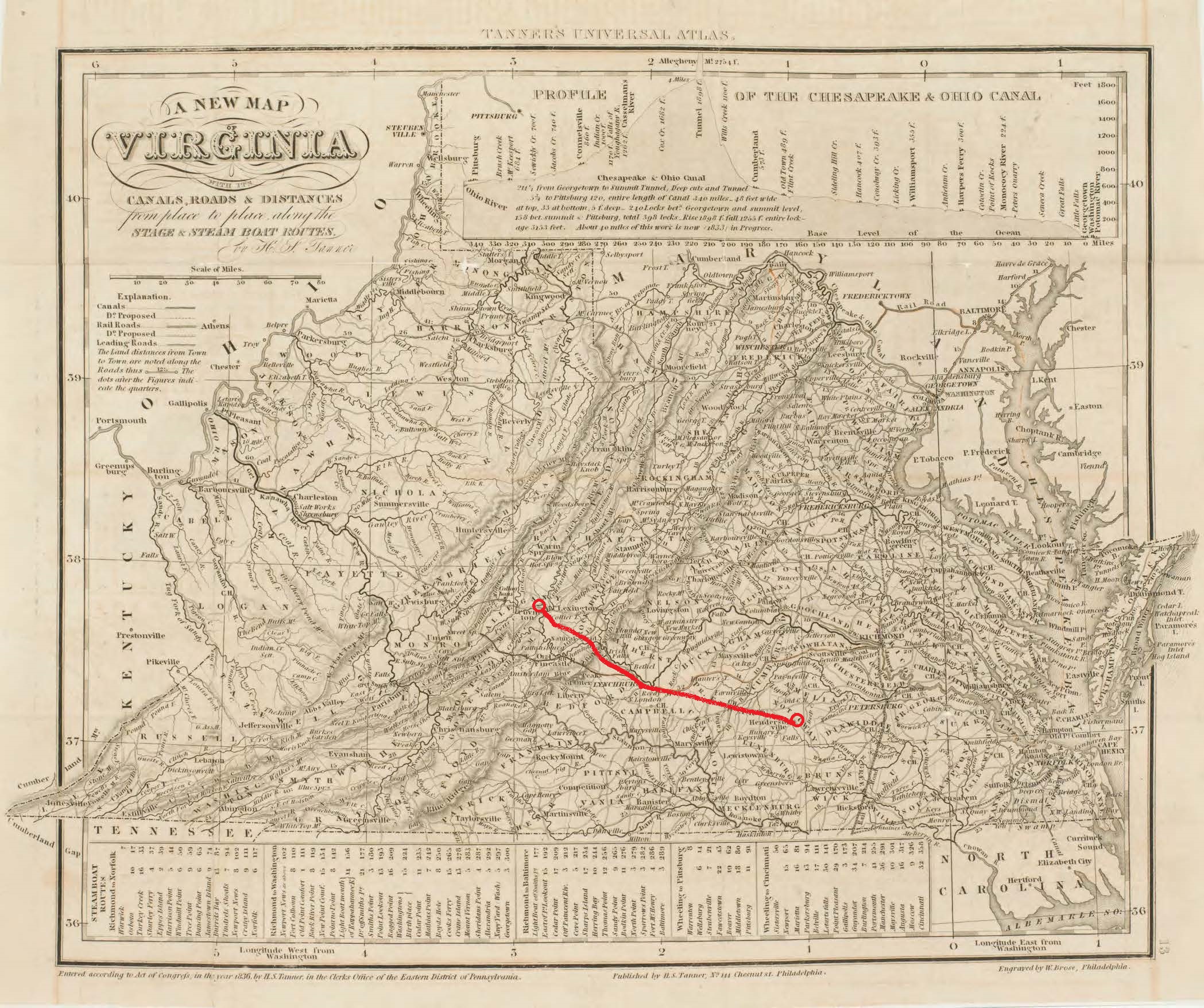

In 1842, an enslaved man in Nottoway County named Joe no longer wanted to live in bondage. He chose to emancipate himself from his enslaver, John Finney, and headed northwest through Virginia for freedom in Ohio or Pennsylvania. Following today’s U.S. 60, the journey would cover over 160 miles and take 55 hours on foot. Other than the clothes he wore, Joe took only a couple pairs of pants, a pair of pincers, and a small knife. Joe’s journey was surely demanding, and not only due to the physical toll of travelling on foot through difficult terrain with very little food and sleep. The fear of being captured either by his enslaver or by local “slave patrols” must have constantly haunted him. If recaptured and returned to his enslaver, Joe would face severe punishment, perhaps dozens of lashes on his bare back or an iron collar around his neck.

Joe made his way across the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Shenandoah Valley and reached the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. As he began his crossing of the Appalachians, Joe was captured in Alleghany County and committed to the county jail on 30 July 1842. Local authorities questioned Joe. They wanted to know his name, where he came from, and the name of his enslaver—all of which Joe provided.

As required by Virginia law, the Alleghany County jailor posted ads about Joe in a local newspaper, the Western Whig, and a statewide newspaper, the Richmond Enquirer, for six weeks. The advertisements provided a detailed description of Joe—his estimated age, skin tone, clothing, items found on him, his manner of speech—so that Joe’s enslaver would be made aware and claim his “property.” If Joe’s enslaver did not claim him within four months after the last ad was published, the Alleghany County sheriff could sell Joe at an auction to the highest bidder. Joe’s enslaver, John Finney, never came to Alleghany County to claim him. After spending nearly a year in the county jail, the Alleghany County sheriff sold Joe in front of the county courthouse on 15 May 1843 to Andrew Dawson for $170. In 2021, that equates to nearly $6,000.

After the sale, as required by law, the jailor filed a report with the county court. In it, he listed the expenses the county incurred from Joe’s incarceration and sale. These expenses were paid from the $170 the county made from the sale of Joe. Sheriff Sampson Sawyer charged $8.50 for conducting the auction; the jailor, James T. Baker, charged $93.15 for Joe’s food and clothing while he was incarcerated; the county clerk, Andrew Judge, charged $3.00 for copying and certifying the jailor’s report. What became of the remaining $66.35? According to Virginia law, after expenses, local officials sent any funds remaining from the sale of enslaved people recaptured while seeking freedom to the Auditor of Public Accounts, who placed the money in a trust known as the Literary Fund. The Virginia state government created the trust in 1811 and designated that the money be used to build schools and educate poor white children.

What does the “Runaway Slaves” Records collection tell us? First, contrary to contemporary (and some current) assertions, enslaved people were not content with being held in servitude against their will. They wanted freedom and took great risks to attain it. Second, local and state governments participated in and profited from human trafficking. “Slave auctions” were not only conducted by private individuals or businesses. Public officials regularly auctioned off enslaved people in front of every city and county courthouse in the commonwealth. Moreover, the money from the sale of enslaved Black individuals and people of color seeking their freedom, like Joe, went to white local government officials who captured, imprisoned, and sold them to the highest bidder. Any additional money from the sale of enslaved people funded the education of poor white children.

The purpose of Virginia Untold is to shed light on these and other unsettling truths that have been hidden in the records of the commonwealth for far too long.