Visiting John and Lucinda Smith at their home in Belton, South Carolina, could be a little complicated if one were traveling from out of town. That was the case when Lucinda’s brother, William E. Morris, was planning his trip from Dinwiddie County, Virginia, in September 1864. His brother-in-law, John Smith, mailed William detailed instructions on how to proceed. After changing trains in Columbia, William should arrive at the Belton depot in the evening with plenty of time to make the 4 ½ mile walk to “Calhoun” before dark. He could ask anyone and they could “put you in the road” to Calhoun, the letter read. However, William was especially instructed, to “notice the following”:

William when you get to Belton do not call my name to any body [sic], but just enquire the way to Calhoun. Be sure to do this. And as you come to Calhoun or after you get to our little town don’t call my name but just enquire where the teacher lives and when you get to my house I will tell you my reason for doing this.

Teaching has always been deemed an important and honorable profession, and in the South during the Civil War, educators were exempt from Confederate military service. That was the case with Mr. John E. S. Smith. Smith, who was possibly from Kentucky (or South Carolina), married Lucinda Morris of Dinwiddie County, Virginia, in December 1859. Born in Mecklenburg County, Virginia, Morris was only 15 when she married the 31-year-old school teacher.

Not surprisingly, Smith’s background was a little more problematical than he explained to his young wife. The 1860 census indicates that a five-year-old Lewis C. Smith, also from Kentucky (or South Carolina) was a member of their household. Lewis was in all likelihood a child from the husband’s previous marriage, but we are uncertain how he explained the child to his wife.

In December 1860, the couple had their first and only child together, Mary Alice Smith. In August 1861, Smith moved the family to South Carolina to take a post as a teacher. Sometime after, Lucinda Smith learned that her husband’s real name was not Smith, but was in fact Stephens (or Stevens). Not only that, but Lucinda learned that her husband had been married before, was still married, and had “several children then living.” Even with this, she continued to live with him for a time, “discharging the duties of a wife” until one day, “under the pretense of seeking business in an other [sic] part of the state in the neighborhood where his first wife lived” he left, she felt, for good. In December 1864, she “being thus abandoned returned to Virginia & her former family.”

December 1864 pass, issued by Elijah Webb, clerk of the court of common pleas for Anderson District, South Carolina, vouching for ``Lucinda Stephens`` to get through Confederate lines to ``visit relatives`` in Virginia. She had no intention of returning from her visit.

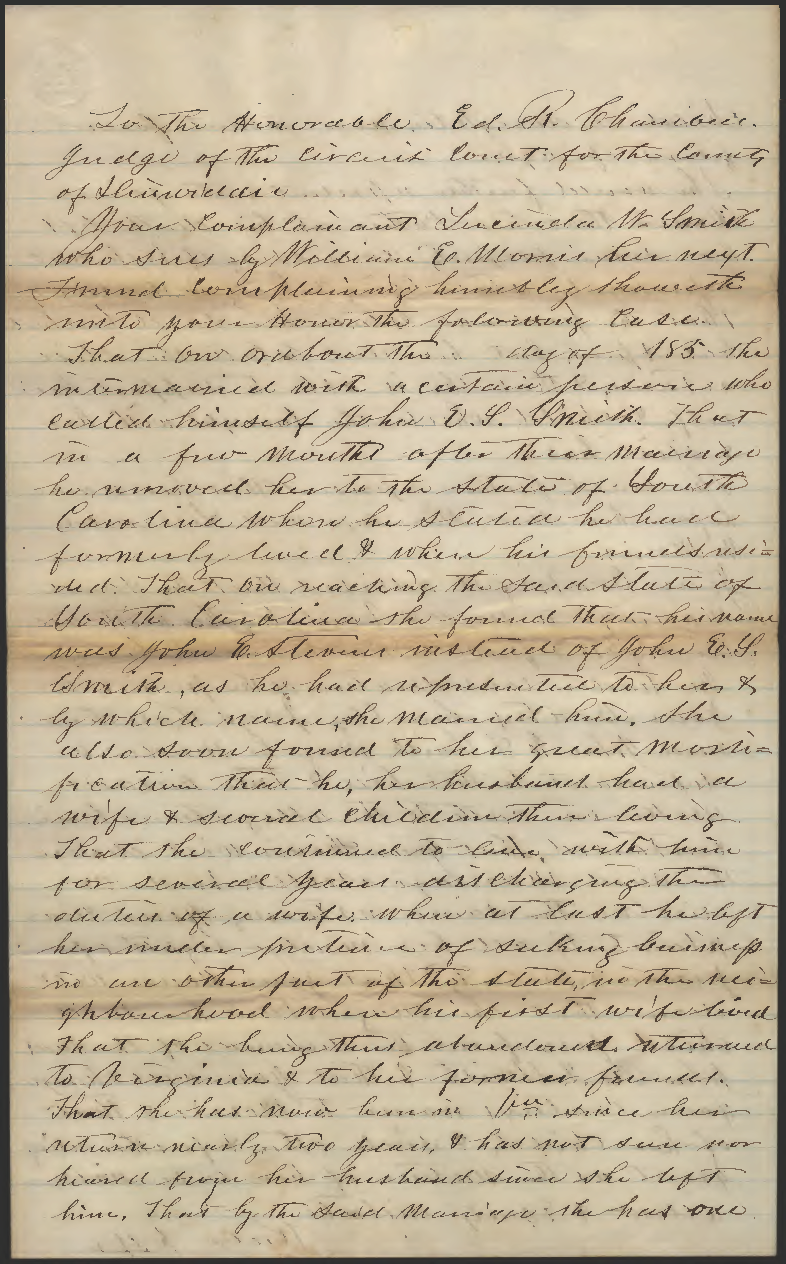

From the divorce suit filed by Lucinda W. Smith against John E. S. Smith (Dinwiddie County Chancery, 1866-006).

But wait, it gets worse. When Lucinda Morris’s father, John C. Morris, died in 1854 he had left her “some property consisting of both real & person estate lying & being in” Dinwiddie County. Her husband had spent much ($456.00) of her inheritance but she still had the real estate property, with which she believed she would be “able to support herself & child which she brought with her & still has.”

Once Lucinda left for Virginia, things began to unravel for John Smith. When a Southside Railroad train stopped at the Junction (the intersection with the Richmond and Danville Railroad in Nottoway County) in December 1864 a “military guard” requested that Dinwiddie Courthouse attorney Isaac Keeler see a prisoner, who turned out to be Smith. According to Keeler’s deposition, Smith “had a pass to travel exempt from military duty as a school teacher” which was issued by the clerk of court from Anderson District South Carolina. The name on the pass was for John E. Stephens. Lucinda, who was there, insisted that his name was Smith. In time, however, he confessed to Keeler that his name was in fact Stephens. He indicated that he had returned to their home in Belton and saw that Lucinda was gone, was traveling after her, and had overtaken her at the Junction. “When she declined to return with him upon the grounds that he had another wife, he stated that he had a former wife, but they had not lived together in so long that he thought he had a right to get married again, that he had one child by his former marriage he kept with him, that his first wife left him because she said she did not wish to live with him.” Keeler noted that the military guard had taken a few items from Smith, including “a gold watch chain and some other jewelry,” which they “delivered to the plaintiff.”

In September 1866, the “illegal marriage” was declared “null & void” and she resumed her life under her original (maiden) name, Lucinda W. Morris. It is difficult (if not impossible) to determine what became of John E. S. Smith (or John E. S. Stephens, or John E. Stephens, or John E. S. Stevens, etc.) or Lewis C. Smith (or Lewis C. Stephens, or Lewis C. Stevens, etc.).

Not so difficult to follow, however, are Lucinda W. Morris and her daughter Mary Alice Smith, who retained the fictitious name of her father. In January 1870, 24-year-old Lucinda Morris married 33-year-old Confederate veteran and wheelwright/coach maker Thomas R. Hitchcock, and over the course of their lives they had two children, who would be half-sisters to older Mary Alice. Records indicate that Lucinda served as the postmaster for the Goodwynsville post office from at least 1888-1891 and that by the time that she died in April 1917 she had enough of an estate that it had to be sorted out in another Dinwiddie County chancery suit. Her husband died two weeks after her and Mary Alice Smith Thompson died in 1920.

The complete divorce suit between Lucinda W. Smith and John E. S. Smith (Dinwiddie County Chancery 1866-006) and the Heirs of Lucinda Morris Hitchcock vs. Heirs of Lucinda Morris Hitchcock (Dinwiddie County Chancery, 1929-006) can be viewed online at the Chancery Records Index.