Author’s Note: The spellings of names evolved over time. In order to be consistent, names were spelled as they appeared in government records.1

On Tuesday, 4 October 1921, the Newport News Daily Press, the Virginian-Pilot, and The Norfolk Landmark reported the death of 22-year-old Greek immigrant George Andrews. George Andrews and his friend/employee, Kyriakos Tsoularakis, had agreed to transport two Japanese sailors from Hampton to Pine Beach (Sewall’s Point) to rejoin a Japanese ship that was flying the English flag at sea. According to Tsoularakis, around 4:30 p.m., while Tsoularakis was steering the boat, Andrews was shot and thrown overboard by one of the men, perhaps because Andrews was known to carry large sums of money. The two Japanese men then shot wildly and jumped into the water themselves. Although others heard the cries for help, Tsoularakis was the only eye witness.

Tsoularakis returned to Hampton around 6:00 p.m. and reported the incident. The authorities and Tsoularakis attempted to find Andrews’s body and a ship with a Japanese crew that night, but a storm forced them to return to shore before achieving either objective.

Upon returning to land, Tsoularakis was jailed because the police believed that he knew more about the situation than he admitted, and he had $230 in damp bills hidden in his dry clothing. The boat was searched, and while a fully loaded revolver and hammer were found, there was no blood. There were suspicions that bootlegging may have also been a factor given that it was a problem in the area.2

The Murder Investigation

Later newspaper reports describe how federal, state, and local authorities, as well as the Greek community, investigated the case and uncovered many more details. It was quickly apparent that they were dealing not with a single homicide, but with a triple murder.3

Several days before their deaths, on 3 October, the two Japanese men, Hireichi Hironomi and T. Azuma, who “were hard up for money one of them having been said to have pawned his clothing in Norfolk several days” before4 were “seen in West Queen Street and also in the yard of the home of George A. Lake, on Hampton creek.”5 Hironomi and Azuma had arrived at the Virginia Hotel in Hampton at 11:00 a.m., left, and returned again at 3:00 p.m. Apparently, they had been looking for George Andrews, although Tsoularakis claimed that Andrews did not know them. John Nikas—George Andrews’s brother-in-law—sat with them while they waited that afternoon. Azuma communicated via written English, which he said that he learned in school in Japan. Hironomi slept.6

According to the Daily Press, “the lead man [Azuma] had worn brown clothes and a pair of shoes with black bottoms and tan tops.” He was “a powerfully built young man, with strong arms and limbs, and among the people who have heard of him, was known as an expert in athletics.” The other Japanese man—Hireichi Hironomi—“was much taller” and “wore a blue suit of clothes.”7

On that same day, 3 October, Tsoularakis, George Andrews, Tsoularakis’ friend/employer, and a third man by the name of John Schootis set out at 9:30 a.m., searching, unsuccessfully, for whiskey aboard the ships in the harbor. Andrews took the lead in this mission; he boarded the ships one by one, staying no more than five to ten minutes on each. All three men returned to Hampton by 3:30 p.m. As they were docking the boat, Andrews fell into the water.8

Azuma and Hironomi were waiting at the Virginia Hotel for George Andrews when he and Tsoularakis returned to the hotel. (John Schootis opted to go to Newport News instead.) John Nikas was present as well and remembered that Andrews’ pockets were full of wet money, presumably from his fall in the water. There was a discussion over Andrews selling Azuma and Hironomi thirteen cans of whiskey, although Nikas later claimed that there was no whiskey. Around 4:00 p.m., Tsoularakis, Andrews, Azuma, and Hironomi all left the hotel.

When Tsoularakis and Andrews purchased gasoline and oil late that afternoon, they were originally believed to be the only ones in the boat, but Tsoularakis later revealed that Azuma and Hironomi were in the boat’s cabin at the time. W. B. Nelms, who was employed by Texas Oil Company and from whom the gasoline and oil were purchased, remembered that they left at 5:05 p.m., slightly after closing time. At some point, Tsoularakis received $100 and then $130 from Andrews for selling whiskey, which accounts for why Tsoularakis had so much wet money in his pockets.

Lawrence W. Wallace testified that Andrews was steering the boat and that Tsoularakis appeared to be arguing with him, although Tsoularakis claimed that he was the one steering. The dispute may have concerned a married woman named Ruth who was first associated with Andrews and then with Tsoularakis.

Ultimately, Andrews and Azuma—both of whom had pistols— someone ended up in the water, followed by Hironomi, who had a hammer, but dropped it before going overboard according to Tsoularakis though he claimed to have not heard any arguments. Others nearby heard around 5:00 p.m. but did not see anything. Upon returning to Hampton, Tsoularakis told John Nikas about the accident, and he recommended reporting it to the police. In what was perhaps a separate encounter, restauranteur James Stassinos also encouraged Tsoularakis to notify the police.9

On the afternoon of Thursday, 6 October, George Andrews’s body was found “in the water near the black bouy [sic] and a few hundred yards” from where the boat was when he went overboard10 and returned to land at the Hampton Shipbuilding Company by Capt. J. M. Phillips.11 Andrews had been shot in the right side of his chest and hit in the head, although drowning was the ultimate cause of death. The coroner also found $500, (although it was believed that he had $1,200 on him at the time) as well as a gold watch.12 As noted by the reporter, “If Tsoularakis had any misgivings he failed to exhibit the slightest emotion or fear under the trying circumstances.” “He was returned to the cell in the Hampton jail protesting his innocence all the way back.”13 On Sunday, 9 October in a funeral officiated by a Greek priest, Andrews was buried in Oakland Cemetery.14

On the same day, Azuma’s pocketbook was found near Hampton Institute. Given that it was “hidden under one of the section of board walks near the boat house,” it was suspected that Azuma had been robbed after he was killed, and the pocketbook had been hidden. This discovery convinced authorities that instead of Andrews having been murdered, by the two Japanese men who then escaped, that in fact all three men had been murdered in a triple homicide.15

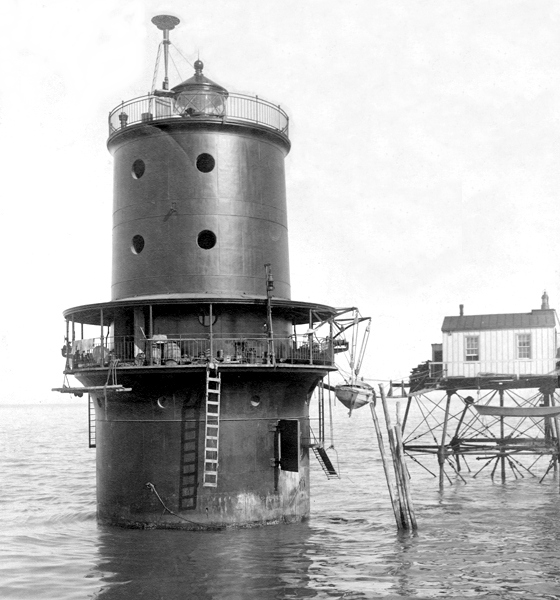

Azuma’s body was not found until 10:30 a.m. the following day near Thimble Lighthouse—three miles from the accident—by Capt. J. T. Twiford, who kept the station. The coroner found no “marks of violence, and no papers of any sort, through which identification could be made,” although there was a paper with Japanese writing in one of Azuma’s pockets. Azuma was identified by members of the Japanese community in Norfolk16 and was to be buried in the county cemetery because he was “without funds and relatives in this section” and barely known in the community.17 The reporter declared that Tsoularakis “showed absolutely no emotion” upon hearing the news and that the “officers were unable to shake Fsoularakis [Tsoularakis] in his story of the tragedy.”18

The body of Hireichi Hironomi was not recovered until 9 October, when it was found in a fishing net in Cape Charles.19 His body was examined by coroner W. F. D. Williams and physician Carlisle L. Nottingham of Northampton County, and they determined that he “had been stabbed severely under the left arm,” which was enough to cause death. No water was found in his lungs, which eliminated drowning as a cause of death. Given that Tsoularakis stated that only Azuma was involved in the argument, the finding was unexpected. Investigators found it curious that Azuma and Hironomi were found so far from where the accident supposedly occurred, and they speculated that their bodies may have been “carried out to the main channel and dumped into the water.” They may have even been killed before Andrews.20 No one claimed Hironomi’s remains and he was buried in Northampton County.21

The coroner’s inquisition continued on Monday, 10 October, and once again, Tsoularakis was asked to describe the accident. This time, he “asked for an interpreter because he can speak better Greek than English. M. P. Licolpotas served in that capacity.” He denied knowledge of a knife.22 A decision could not be reached at the conclusion of the inquisition on Wednesday, 12 October, so the case was heard in police court the next day.23 Once again, no decision was reached, and Tsoularakis was held without bail. According to the Daily Press, Tsoularakis “was visibly disappointed…when the officers took him back to the county jail on the direct charge of first degree murder to hold him until the December session of the Circuit Court. He told Deputy Sheriff Thomas S. Curtis that it would be his death to stay in jail.”24

On 18 February 1922 Tsoularakis was acquitted of the death of Azuma25 after twenty minutes of deliberation. John Schootis, Tsoularakis’s friend who observed the proceedings, was jailed on charges of contempt of court because he “gave vent to his feeling by cheering and springing to his feet.” The Daily Press reported that the courthouse was probably filled with “the largest crowd, which has been at a trial here in several years…Greek residents from all sections of the peninsula, including Norfolk and Newport News.”26

The Daily Press also reported that “Tsoularakis was “still charged with the responsibility for the death of H. Hironomi and George Andrews, the other occupants of the launch, but the impression…was that the cases will be disposed of by a nolle prosequi on the part of the state”, meaning that the charges would be dropped. Since no further records or coverage has been found, this might have been what occurred.

Our Investigation

On 12 February 1922, the Virginian-Pilot and The Norfolk Landmark had reported that “An international bootlegging combine in which the United States, Japan and Greece figure will be unfolded next week when K. Tsoukalarkis [Tsoularakis], Greek, is placed on trial in the Elizabeth City County Circuit Court in Hampton on a charge of triple murder, according to officers interested in the case.” The reality of the trial was far less captivating. But describing each Japanese man as “a man of mystery” is accurate, and this story illuminates how difficult researching recent immigrants can be.27

Because so little information is available about Azuma and Hironomi, they are almost impossible to research. The authorities searched the room that the two men shared in Norfolk, and yet Azuma’s first name is never determined. Initially, his first initial in Latin-script was believed to be A, but after his pocketbook was discovered, T was thought to be correct. Hireichi Hironomi’s surname was initially transliterated as Hiromori and then evolved to Hiromoni, Hiromono, Hironomo, Hirinimo, Honoromia, and finally Hironomi. Tsouklarakis stated that they were sailors on a Japanese ship flying the British flag, but newspapers reported that Azuma worked for a ship’s chandler (a retailer specializing in nautical supplies), and that the two men were known by the Japanese community in Norfolk, where they resided. Hironomi had a tattoo of a United States flag, that may be an indication that he wished to remain in the United States, but it could also just be symbolic of his time in the U.S. It is particularly intriguing given that tattoos were banned in Japan between 1868 and 1948.28 Azuma and Hironomi do not appear to be included in the 1920 U.S. census nor in the 1920 Norfolk city directory, and any associates were either not close enough to or had the means to ensure a proper burial given that the county covered the costs.

Tsoularakis fares slightly better. Although newspaper articles from 1921 give different transliterations for his name as well, specifically Fsoularakis. The case file for his trial identifies him as “K. Tsouklarakis.” Newspapers spelled his first name in a variety of ways: Kyriakas, Kyrisarki, Kyrakaris, Kysarasis, Hyrisikara, Kyrikaris, and finally Karasis. His story reveals how important it is to search every possible record. During his deposition for George Andrews’s inquest, Tsoularakis revealed: “I have been 14 more or less in U.S. all the time in N.N. & Hampton Roads. All the time. Fireman on Eng ship Nicea [?] 1907. to time of coming to U.S. age 27, unmarried.”29

Despite this information, his name does not appear in the 1920 Newport News city directory nor the U.S. census. It is possible that he later became a crew member of ships traveling into New York because there is an individual by the name of Kyriakos Tsoularakis who was born in the mid-1890s found on crew lists for several decades following this incident.30

George Andrews was the easiest to research. The records included in the coroner’s inquest include letterhead indicating that George Andrews was the proprietor of Andrews’ Billiard Parlor, which provided “pocket billiards, cigars, tobaccos and soft drinks” and was located at 3412 Washington Avenue in Newport News. His death certificate reveals that he was born in Candia, Crete, in 1897, to Nicolaos Katselakis (or Andrews) and Annia Orfandki, both of whom were also born in Candia, Crete.31 Unlike the other three men, he appears in multiple records. A World War I draft registration card reveals that ca. 1917, he was living in Hopewell, Virginia, and his parents and two sisters (ages 15 and 17) were dependent upon his work as a barber.

That record indicates that he also went by the surnames Katselakis and Andrailakes and was born 28 December 1895 in Crete.32 A census record from 1920 reveals that at 23 years old, he was living at 3412 Washington Avenue in Newport New, having been born in Greece to Greek parents. He immigrated in 1913 and had started the naturalization process.33 A city directory from the same year indicates that he was a barber at the 3412 Washington Avenue location, so it appears that he became the proprietor of the billiard parlor after working as a barber.34

City of Hampton/Elizabeth City County, Coroner’s Inquisitions, 1921-1925, Box 7, Barcode 7431371, Coroner’s Inquest for T. Azuma, Testimony of John Nikas, 8 December 1921.

Why is there so little information on these four men? In the early 20th century, it was common for members of immigrant communities to be left out of city directories, particularly individuals who did not own businesses. Records often overlook those without wealth and miss those who are transient. Those who engaged in bootlegging, as some suspected these men to be, might prefer to remain in the shadows as much as possible. A lack of uniformity in the spelling of names makes it difficult to determine if the correct person has been identified in records. The Greek and Japanese languages do not use the Latin alphabet, so spellings using the Latin alphabet may not be uniform. There was also a language barrier, given that one of the Japanese men did not know English, another could only write it, and Tsoularakis requested an interpreter for his testimony to make communication easier. There may have been a lack of interest given attitudes towards immigrants at the time.

The concept of immigration quotas had developed by 1921. These quotas were often based on how many immigrants from particular countries were in the U.S. at the time the census was taken. Western Europeans were the most likely to immigrate to the U.S. early on, so their larger numbers resulted in a higher quotas. Immigration from other countries—such as Greece—started later, so their numbers were more likely to be smaller. It was also the era of “Yellow Peril,” which was a fear that Japanese (and other Asian) immigrants would take over the West Coast. Although “Yellow Peril” was not as strong in Virginia, Azuma and Hironomi are referred to by the racial epithet “Jap” in newspaper articles.35

Ultimately, we will never know what transpired in the boat as it sailed between Hampton and Sewall’s Point. Only Tsoularakis had any idea how the boat’s other three passengers ended up in Hampton Creek, and even he may not have known the entire story. Tsoularakis was acquitted, but the case remains a mystery, as do all who were involved with it.

Header Citation Image

Thimble Shoal Lighthouse and remains of previous screwpile lighthouse. Photograph courtesy U.S. Coast Guard

Footnotes

[1] Virginia, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death Certificate No. 21762 for T. Azuma, 9 October 1921; Virginia, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death Certificate No. 22735 for Hireichi Hironomi, 10 October 1921; City of Hampton/Elizabeth City County, Coroner’s Inquisitions, 1921-1925, Box 7, Barcode 7431371, Coroner’s Inquest for T. Azuma, Testimony of John Nikas, 8 December 1921; City of Hampton/Elizabeth City County, Coroner’s Inquisitions, 1921-1925, Box 7, Barcode 7431371, Coroner’s Inquest for George Andrews, Testimony of John Schootis, 8 December 1921; Search of AncestryInstitution for Kyriakos Tsoularakis, born 1895 ±2, https://www.ancestryinstitution.com/search/?name=Kyriakos+_Tsoularakis+&birth=1895&birth_x=2-0-0, accessed 23 April 2022.

[2] “Japs Kill Greek, Story of Friend,” Virginian-Pilot and the Norfolk Landmark (Norfolk, VA), 4 October 1921, 1; “Boatman Tells Story of Shooting By Jap Seamen And Is Held As Witness,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 4 October 1921, pp. 1, 10.

[3] “Triple Murder May Be Proven When Story Of Boatman Is Traced Out,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 5 October 1921, p. 1.

[4] “Hope To Find Second Jap’s Body To Solve Hampton Murder Quiz,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 8 October 1921, pp. 1, 7.

[5] “Two Missing Japs May Be Connected In Triple Murder,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 6 October 1921, p. 1.

[6] “Hope To Find Second Jap’s Body To Solve Hampton Murder Quiz,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 8 October 1921, pp. 1, 7; City of Hampton/Elizabeth City County, Coroner’s Inquisitions, 1921-1925, Box 7, Barcode 7431371, Coroner’s Inquest for T. Azuma, 8 December 1921; “Triple Murder May Be Proven When Story Of Boatman Is Traced Out,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 5 October 1921, p. 1; City of Hampton/Elizabeth City County, Coroner’s Inquisitions, 1921-1925, Box 7, Barcode 7431371, Coroner’s Inquest for George Andrews, 8 December 1921.

[7] “Hope To Find Second Jap’s Body To Solve Hampton Murder Quiz,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 8 October 1921, pp. 1, 7.

[8] City of Hampton/Elizabeth City County, Coroner’s Inquisitions, 1921-1925, Box 7, Barcode 7431371, Coroner’s Inquest for George Andrews, 8 December 1921; “Inquest Over Bodies Of Boat Tragedy Victims Continued By Coroner,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 11 October 1921, p. 1

[9] “Triple Murder May Be Proven When Story Of Boatman Is Traced Out,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 5 October 1921, p. 1; City of Hampton/Elizabeth City County, Coroner’s Inquisitions, 1921-1925, Box 7, Barcode 7431371, Coroner’s Inquest for George Andrews, 8 December 1921; “Inquest Over Bodies Of Boat Tragedy Victims Continued By Coroner,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 11 October 1921, p. 1; “Coroner’s Jury Is Unable To Place Blame For Death Of Three In Boat Mystery,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 13 October 1921, p. 1; “Two Missing Japs May Be Connected In Triple Murder,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 6 October 1921, p. 1; “Hope To Find Second Jap’s Body To Solve Hampton Murder Quiz,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 8 October 1921, pp. 1, 7; City of Hampton/Elizabeth City County, Coroner’s Inquisitions, 1921-1925, Box 7, Barcode 7431371, Coroner’s Inquest for T. Azuma, 8 December 1921; “Fsoularakis Held For The Grand Jury On Murder Charge,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 14 October 1921, p. 1; “Greek Not Guilty Of Murdering Jap Jury Quickly Finds,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 19 February 1922, p. 1; “Boatman Tells Story of Shooting By Jap Seamen And Is Held As Witness,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 4 October 1921, pp. 1, 10.

[10] “Find Body of Greek Bumboater in Roads,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 7 October 1921, p. 13.

[11] “Andrews’ Body Found Near Spot Where His Partner Said He Died,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 7 October 1921, pp. 1, 2.

[12] “Andrews’ Body Found Near Spot Where His Partner Said He Died,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 7 October 1921, pp. 1, 2; “Find Body of Greek Bumboater in Roads,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 7 October 1921, p. 13.

[13] “Andrews’ Body Found Near Spot Where His Partner Said He Died,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 7 October 1921, pp. 1, 2.

[14] “Inquest Over Bodies Of Boat Tragedy Victims Continued By Coroner,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 11 October 1921, p. 1.

[15] “Find Body of Greek Bumboater in Roads,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 7 October 1921, p. 13; “Andrews’ Body Found Near Spot Where His Partner Said He Died,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 7 October 1921, pp. 1, 2.

[16] “Hope To Find Second Jap’s Body To Solve Hampton Murder Quiz,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 8 October 1921, pp. 1, 7.

[17] “Jap Found in Bay at Cape May Be Last One,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 10 October 1921, p. 3.

[18] “Hope To Find Second Jap’s Body To Solve Hampton Murder Quiz,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 8 October 1921, pp. 1, 7.

[19] “Jap Found in Bay at Cape May Be Last One,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 10 October 1921, p. 3; “Body of Second Jap Found Has Big Wound Under Arm,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 11 October 1921, p. 3.

[20] “Body of Second Jap Found Has Big Wound Under Arm,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 11 October 1921, p. 3.

[21] “Inquest Over Bodies Of Boat Tragedy Victims Continued By Coroner,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 11 October 1921, p. 1.

[22] “Inquest Over Bodies Of Boat Tragedy Victims Continued By Coroner,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 11 October 1921, p. 1.

[23] “Coroner’s Jury Is Unable To Place Blame For Death Of Three In Boat Mystery,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 13 October 1921, p. 1.

[24] “Fsoularakis Held For The Grand Jury On Murder Charge,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 14 October 1921, p. 1.

[25] “Tried for 3 Murders, Touklarasis Freed,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 19 February 1921, p. 10.

[26] “Greek Not Guilty Of Murdering Jap Jury Quickly Finds,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), 19 February 1922, p. 1.

[27] “Triple Murder Charged To Greek In Booze Fight,” Virginian-Pilot and The Norfolk Landmark, 12 February 1922, p. 11.

[28] Hikari Hida, “Discreetly, the Young in Japan Chip Away at a Taboo on Tattoos,” The New York Times (New York, NY), 23 April 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/23/world/asia/japan-tattoo.html.

[29] City of Hampton/Elizabeth City County, Coroner’s Inquisitions, 1921-1925, Box 7, Barcode 7431371, Coroner’s Inquest for George Andrews, 8 December 1921.

[30] Search of AncestryInstitution for Kyriakos Tsoularakis, born 1895 ±2, https://www.ancestryinstitution.com/search/?name=Kyriakos+_Tsoularakis+&birth=1895&birth_x=2-0-0, accessed 23 April 2022.

[31] Virginia, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death Certificate No. 21763 for George Andrews, 4 October 1921

[32] Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 [database on-line] (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005), Registration for George Katselakis or Andrailakis (alias Andrews), ca. 1917.

[33] Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line] (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010), Images reproduced by FamilySearch, Entry for L. George Andrews, Ward 4, Newport News, Virginia, Supervisor’s District 347, Enumeration District 112.

[34] Newport News, Kecoughtan, Hampton, Phoebus and Old Point, Va. Directory 1920, Vol. 24 (Richmond, VA: Hill Directory Co., Inc., 1920), 106.

[35] An Act To limit the immigration of aliens into the United States, Public Law 5, U.S. Statutes at Large 42 (1921): 5-6; United States, Bureau of the Census, Social Science Research Council, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789-1945; a Supplement to the Statistical Abstract of the United States (Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1949), 33-34; Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America: A History (New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 2015), 124.