In October 1842, Cora Ann Elizabeth Carter and her husband William Watt Hubbard boarded the steamboat Patrick Henry en route for New York. Earlier that morning, Carter had approached a gentleman asking him the best way to get to New York. Carter told the man that she was a free woman and that she had bought her husband. When the steamboat captain, Zebulon Mitchell, asked for Hubbard’s free papers, Hubbard looked to his wife, Carter, who produced a slip of paper indicating Hubbard’s free status. The note claimed that Carter, a free woman, had purchased her husband for $750 from his enslaver, Richard Stoakes. According to the note, Hubbard was a free man.

Carter explained to Mitchell that she had purchased her husband in July 1841. Mitchell questioned her: the note was dated July 1842. Carter reasoned that the incorrect date must have been the result of some mistake at the courthouse. Mitchell was not convinced. He planned to detain the couple and then carry them back to Richmond. He pressed Carter to confess, telling her that she might as well tell the truth. Carter then revealed that the note was a forgery. She had never paid for her husband’s freedom. He was still an enslaved man.

Captain Mitchell turned the boat around. Once it arrived back in Richmond, he called for William B. Page, who further questioned Carter. When confronted by Page, Carter shared a different story. She had not purchased Hubbard. This man called Hubbard had “ruined” her. The day prior, Page had seen Carter at the Mayor’s Office. He claimed that Carter had been “trying to get a paper from the mayor stating that she was the person mentioned in her free papers, for the purpose of leaving the papers at the Railroad depot.” According to Page, she was trying to get to Cincinnati. She had no money to pay for her passage but a female friend who was supposed to accompany her was to pay her fare.

Captain Zebulon Mitchell's deposition detailing his conversation with Cora Ann Carter onboard the steamboat.

Commonwealth versus Cora Ann Elizabeth Carter, 1843, (unprocessed). City of Richmond Circuit Court Records. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

Almost a year later, this case went to trial in the Richmond City Hustings Court. In December 1843, Carter was charged with “feloniously enticing advising and persuading William Watt Hubbard a slave the property of Richard Stoakes to abscond from his owner… and in then and there feloniously procuring furnishing and delivering for said slave… a certain writing.” Four individuals provided depositions in Carter’s case. Three were white men (Zebulon Mitchell, Thomas Lyall, and William B. Page) and the last was Hubbard, who simply stated that he was in fact an enslaved man and that he had received the paper produced in court from a man named James Banks.

Carter was charged according to an Act of Assembly passed in March 1834 which stated, “That if any free person shall entice, advise or persuade any slave to abscond from his or her owner or possessor, or shall procure, furnish or deliver to, or for any slave any register, pass, or other writing whatsoever, or any money, clothes or provisions, with intent in so doing to aid such slave to abscond…shall be deemed guilty of a felony, and on conviction, shall be sentenced to imprisonment in the public jail and penitentiary house for a period not less than two nor more than five years.”1 Carter received the full sentencing: five years’ imprisonment in the penitentiary.

But there is another crucial player in this story: the man who forged Hubbard’s fake pass. James Banks, a free Black man living in Richmond, was apparently known in the city as someone who could write very well. Two different men testified as much. Thomas Harris claimed that he had seen Banks write often and that the paper produced in court “resembles the handwriting of the prisoner very much.” Hubbard had also known about Banks’ skills and claimed to have known the man for “a long time.” When Hubbard approached Banks with his idea for a forged pass, Banks corrected it and wrote him a new one. Hubbard gave the corrected pass to his wife, Carter, who had it in her possession when the couple boarded the steamboat.

Thomas Harris' statement was recorded along with several others in a deposition for Banks' case.

Commonwealth versus James Banks, 1843, (unprocessed). City of Richmond Circuit Court Records. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

Banks was given the same sentence as Carter: five years’ imprisonment in the penitentiary. The court charged Banks with a different crime: “making, forging, and counterfeiting a certain writing.” His indictment included the verbatim language from the note Banks forged and the note itself was included as evidence in his court case papers.

The note forged by Banks was included as evidence in the court case documents. Dated 15 July 1842, the note is ``signed`` by Richard Stoakes, Hubbard's enslaver, and two other public officials.

Commonwealth versus James Banks, 1843, (unprocessed). City of Richmond Circuit Court Records. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

Unfortunately for us, many of the antebellum records from the Virginia State Penitentiary located in Richmond were lost during the Civil War, which means we cannot confirm that Carter or Banks were imprisoned there. Construction on the original penitentiary building began in 1797, and it opened in 1800. Its location (on land bordered by modern-day South Belvidere, Spring, and Byrd Streets) was considered a remote place at the time. The original building was replaced in the 1920’s, but the penitentiary continued to be situated at the same location until it finally closed in December 1990.2 In spite of the record loss and the building’s absence on the landscape, there are actually quite a few other extant record sets located at the Library and beyond which enable us to piece together the experience of prisoners during this time. For example, the House Journals which are available online for free via HathiTrust include correspondence and reports about the State Penitentiary.

The House Journals for many years include the Annual Report of the Board of Directors of the State Penitentiary. The 1844 report noted that from October 1843 to September 1844 the penitentiary received twenty-four white men, one white woman, eight colored men and one colored woman. Could Banks and Carter have been among the “colored” convicts? The report also included individuals who had died, been pardoned, or discharged resulting in a remaining sixty-five colored men and five colored women. Section five of the report relates the breakdown of charges and sentences. Just one convict had been charged with “aiding slave to abscond” and six charged with “forgery.” This would account for both Carter and Banks’ crimes. In addition, the report includes convict ages, places of birth, illness, death, and employment (while imprisoned).3 Further down, the report includes a list of free men of color received into the penitentiary, but James Banks’ name is not among them. There was no list for free women of color in the 1844 report, and none listed the following year for either sex.

In 1843, the House Journal describes improvements considered for heightening the walls of the Penitentiary, increasing output on the manufacturing industries created at the Penitentiary, and employing more guards, among other things. According to a letter from State Penitentiary Board of Directors President Robert G. Scott, in the past year (1843) “a spirit of insubordination and rebellion has manifested itself in the prison…”4 One can only wonder if this would’ve meant harsher penalties for Carter and Banks in the years to follow. As researchers in the twenty-first century, we can only speculate, but further reading in the House Journals continues to paint a picture of life for those who were imprisoned in the State Penitentiary during antebellum years.

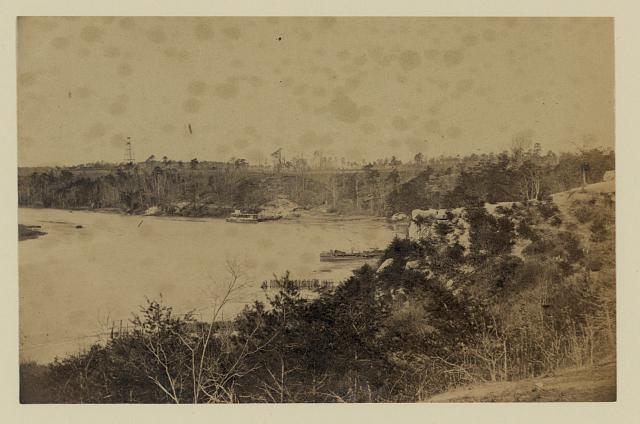

This photograph of the State Penitentiary may have been taken in April 1865.

Credit: National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/524529

What happened to William Watt Hubbard, Carter’s husband? Well, thanks to our friends at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture (VMHC) we know at least part of the story that we couldn’t otherwise glean from the loose records. The Richmond City sergeant kept a register book documenting city crimes and prisoners in the city jail. The register for 1841-1846 survives. On 13 October 1843, the sergeant recorded that William Watt Hubbard had been committed to jail. Hubbard spent nearly three months in jail until he was discharged back to his enslaver Richard Stoakes in January 1844. The entries in this register book match names of convicted individuals that appear in both loose documents of Commonwealth Causes and jail reports from Richmond City court records. At some point these register books ended up at what was the Virginia Historical Society, now the VMHC. We recently worked with VMHC’s staff to transfer them to the Library of Virginia to accompany the loose Richmond City records, which will soon be digitized as a part of Virginia Untold.

We wonder why Carter related two different stories when approached by Captain Mitchell and William B. Page aboard the steamboat. Recent scholarship has highlighted the importance of women’s roles in the fugitive narrative for enslaved people.5 Historically, the literature has focused on enslaved men and their ability to flee bondage more readily because they were not as tied to family. However, books such as Karen Cook Bell’s Running from Bondage focus on understanding the role of Black females in “building a culture and a politics of resistance to slavery.”6 Cora Ann Carter was not enslaved. We don’t know the circumstances around her free status. But we do know that her world was deeply intertwined with those who were enslaved. Like Cook has suggested, her story offers a lens to better understand women’s challenges to structures of power.7 If we interpret the documents to suggest that Carter was in fact shepherding her husband to safety, this means she risked her own freedom for the life of another in the hopes that they might share freedom together. If Carter was in fact fleeing her husband, it proves that she was crafty enough to devise a scheme that would procure her freedom from her husband. Enslaved and free women took bold and intentional steps to alter their fates.

Many questions remain, but as one scholar recently suggested, we don’t necessarily need to know all the details in order to share the story.8 Additional records fill in some, but not all gaps. Entries in the minute books for Richmond City in the 1840s indicate that Carter had lost her free register and was issued a duplicate in May 1843, only months before she would take her husband onboard the Patrick Henry.9 Perhaps this was the very instance to which deponent William B. Page was referring when he mentioned seeing Carter at the Mayor’s Office. One day we might know more. Until then, we tell what we can of each story and keep searching for the missing pieces.

These court cases are a part of the Richmond (City) Ended Causes, 1840-1860. These records are currently closed for processing, scanning, indexing, and transcription, a project made possible through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program. An announcement will be made when these records are added to the Virginia Untold project.

Footnotes

- Acts of Assembly (Richmond: Thomas Ritchie, 1834); Jane Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia, (Fauquier: Afro-American Historical Association, 1995), 109.

- Dale M. Brumfield, Virginia State Penitentiary: A Notorious History, (Charleston: The History Press, 2017) 22, 236-237.

- Virginia. General Assembly. House of Delegates. Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Richmond: Commonwealth of Virginia, 1844-1845. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433014925634&view=1up&seq=486&skin=2021&q1=penitentiary (pp. 486-503)

- Virginia. General Assembly. House of Delegates. Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Richmond: Commonwealth of Virginia, 1843-1844. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433014925626&view=1up&seq=423&q1=penitentiary (p. 423)

- In addition to Bell’s work, referenced below, see also work by Stephanie Camp, Cheryl LaRoche, and Jennifer Morgan.

- Karen Cook Bell, Running From Bondage: Enslaved Women and their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 161.

- Karen Cook Bell, Running From Bondage: Enslaved Women and their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 160-168.

- At her book talk hosted at the Library of Virginia on 14 April 2022, Kristin Greene shared this line in reference to the story of Mary Lumpkin featured in her recent publication, The Devil’s Half Acre.

- Richmond City Minute Book, 1842-1844, p. 319.

Citations

Bell, Karen Cook. Running From Bondage: Enslaved Women and their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Brumfield, Dale M. Virginia State Penitentiary: A Notorious History. (Charleston: The History Press, 2017).

Commonwealth versus Cora Ann Elizabeth Carter, 1843, [unprocessed]. City of Richmond Circuit Court Records. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

Commonwealth versus James Banks, 1843, [unprocessed]. City of Richmond Circuit Court Records. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

Guild, June Purcell. Black Laws of Virginia. (Fauquier: Afro-American Historical Association, 1995).

Minute Book, 1842-1844, City of Richmond Circuit Court Records, Barcode #1109091. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

Register of City Sergeant, 1841-1846, City Administration Records, City of Richmond Circuit Court Records. Local Government Records Collection. #781682. The Library of Virginia.

Virginia. General Assembly. House of Delegates. Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Richmond: Commonwealth of Virginia, 1843-1844.

Virginia. General Assembly. House of Delegates. Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Richmond: Commonwealth of Virginia, 1844-1845.