When I arrived as a Virginia Humanities Fellow at the Library of Virginia in September 2021, I did so with the intent to research the white, male artists in Richmond during and after the Civil War, who used their work to support the mythology of the Lost Cause. Despite how much research and effort ex-Confederate promoters devoted to the development of this problematic ideology, little is known about how the visual arts (besides monuments) were appropriated for the grand scheme.1 Since entering graduate school twenty years ago, I have been researching the lives and production of white, male artists almost exclusively. This is no accident as the teaching of history and art history at predominantly white institutions has historically centered white people. At the Library of Virginia, I had what I considered to be a great research project, which involved learning about these artists, tracing their connections with each other and with ex-Confederate groups and ideologies, and looking at the ways their art was used and described. This, I thought, would connect their work with their sympathies and reveal their politics, ultimately showing how deeply artwork was implicated in promoting the white supremacist notions of the Lost Cause.

It may not be surprising that resources about these men are abundant. Photocopies of hundreds of pages of John Adams Elder’s correspondence are in the manuscripts room at LVA. Artists files, with related clippings, newspaper articles, and secondary research is also present. The correspondence of Ezekiel Moses, original sketches by William Ludwell Sheppard (fig. 1), a scrapbook of William James Hubard’s, and many more resources are readily available. Even more documentation is available in local and regional collections. In fact I was overwhelmed with information. These types of resources have been preserved with intention. Antiquarian societies, private individuals, and institutional collections, including that of the Library of Virginia, have privileged and collected the work of these artists at the risk of not remembering, honoring, and collecting African American history across generations.

While I was in Richmond, I visited the exhibition “Unsay their Names” at the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia. Showcasing the photographs of Derek Kannemeyer, the exhibition featured large color photographs taken in 2020 and 2021 that documented the protests and eventual removal of some of the Confederate Monuments in Richmond (fig. 2). The belated realization in some white circles that these monuments are contested racial sites meant to elevate white people while demeaning and intimidating African Americans, has been bitterly evident to the Black community since their inception.

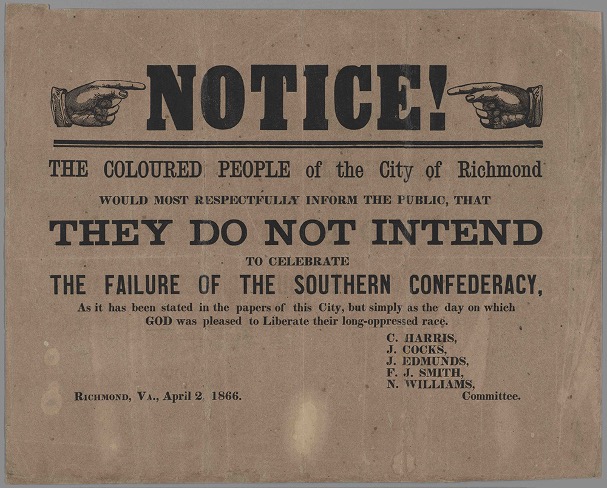

With the help of Kannemeyer’s plea to “Unsay their Names”, the racial reckoning that has taken place in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as my discussions with friends, colleagues, and other scholars, I slowly came to realize that my work, like much of the scholarship on the Lost Cause was unnecessarily centered on the white experience. Rather than working to expose the white supremacist ideologies of the white artists, I began to view the artistic remnants of post-Civil War Richmond squarely within the context of African American emancipation, advancement, and resistance (fig. 3).

African Americans worked to realize an Emancipationist vision of Civil War memory that David Blight describes as having been abandoned by white Americans for the sake of national reconciliation.2 Black freedom and the enactment of citizenship took a variety of artistic and cultural forms, including resistance to white supremacy. The collective energy of African American cultural enactment in the wake of emancipation is the narrative that I decided to tell instead of the unsurprising white artists’ story. Rather than viewing Confederate monuments as promotional of the Lost Cause, might we consider them as a white response to the public pronouncements of citizenship by newly freed people? The Lost Cause artists I spent so much time researching actually operated in response to Black citizenship and its perceived threat.

Many are familiar with the history of events in Richmond from antebellum enslavement, through the war, Reconstruction, elaborate Lost Cause enactments, and finally Jim Crow. The ways in which the arts (especially as produced and utilized by freed people) are integral to this story is perhaps less familiar. Within these histories, I believe that the artistic landscape of the Civil War and Reconstruction years in Richmond reveals much about the efforts of freedmen to enact and pursue citizenship. W. E. B. Du Bois lucidly articulated his protests against the culture of white supremacy, writing in 1903 that he wanted to “reveal fully the other side to the world.”3 Newly freed people were defying generations of racial oppression, and they were celebrating. Arts and culture were applied in a variety of ways to both define and advance citizenship for newly freed people.4

Exactly one year after the burning of Richmond by its own Confederate troops, African Americans staged an Emancipation Day parade that eclipsed anything that the white community was doing publicly at the time (fig. 4). Black Richmonders continued to celebrate Emancipation Day well into the twentieth century. Capitol Square in Richmond had been off-limits to African Americans during the antebellum period. In freedom, Blacks began to gather there, even hosting a July 4th celebration on the grounds in 1866, which involved festooning the Capitol and the Washington Monument with a liberty banner, American flags, and evergreen.5 African Americans were forging a new identity in Southern freedom, enacting their emancipation by voting, holding office, and ultimately resisting white supremacy across a variety of forums. White Richmonders were aghast. I believe that much of the white artistic landscape of the Lost Cause and its attendant racial oppression came in response to these celebrations.

African American resistance is often discussed as an afterthought in Lost Cause scholarship. It is time to turn the tables and consider Black efforts first, as a form of self-empowerment, not simply a response to white actions, the latter which centers the white Confederates. Rather than being reactive, as Joan Johnson has described, “blacks often stressed their American citizenship and contribution to the nation, rather than responding to the precepts of the Lost Cause.”6 Black cultural endeavors across the post-war generations attempted to do this in a variety of media, and according to Blight, by 1909 Black commemorative activity had “emerged everywhere.”7 In Richmond, this culminated in the “National Negro Exhibition” of 1915. It is this type of cultural activity that I now seek to describe and elevate. The white Lost Cause artists should be seen as a footnote to this material.

Beyond celebrating their freedom, elevating portraits of their heroes, and attempting to write inclusive histories, African Americans also offered active opposition to decades of glorification of Confederates in public works of art. Black assembly members and their allies resisted such displays as long as they were in office. As Megan Townes and Claire Radcliffe have demonstrated in a previous UnCommonwealth post, in 1871 the African American state senator Frank Moss opposed the state’s proposition to acquire a portrait of Robert E. Lee by John Adams Elder to hang in the Capitol. As the Richmond Times Dispatch reported, Moss objected on the grounds that “Gen. Lee had fought to keep him in slavery…he couldn’t vote to put his picture on these walls.”

Nevertheless, the state senate passed a vote approving the portrait’s purchase. In 1875, then serving in the House of Delegates, Moss again led efforts to oppose state appropriations for the Thomas J. Jackson sculpture to be placed on the capitol grounds. Again he was outnumbered and an astounding $10,000 was earmarked to move the sculpture to Richmond from England and to make a pedestal for it. Of course, the significance of the white legislators’ efforts to erect Lost Cause monuments was not lost on the Black community. In 1890, the Richmond Planet called Mercier’s Lee statue “a glorification of the lost cause.”8 On December 4, 1909, the newspaper referred to the placement of statues of Davis and Lee in Washington, D. C. as “a fulfillment of all of the radical, moss-back Negro-haters of the Southland.”

African Americans viewed the monuments within the context of the oppression of slavery. On the occasion of the unveiling of Mercier’s sculpture, the Richmond Planet proclaimed that there were undoubtedly men and women in the audience who “had heard the jargon of the auctioneer repeated over their defenceless heads.” A writer for the New York Age noted on the occasion that Lee “was a traitor, and gave his magnificent abilities to the infamous task of disrupting the Union and to perpetuating the system of slavery.”9 From the beginning, African Americans opposed these monuments.

They also organized and celebrated. They promoted monuments of Black heroes, elevating portraits of Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, and others. It is these histories that need to be teased out and told. In them, an incredible American story of citizenship can be found.

Rachel Stephens, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Art History, Department of Art and Art History

The University of Alabama

Footnotes

[1] On the Lost Cause in history and monument, see, for example, David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard, 2001); Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, The Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865-1913 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988); Caroline E. Janney, Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies’ Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012); Cynthia Mills and Pamela H. Simpson, Monuments to the Lost Cause: Women, Art, and the Landscapes of Southern Memory (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2003); and Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997),

[2] The fifty-year advancement of the reconciliationist vision is the subject of Blight’s book, Race and Reunion.

[3] W. E. B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1903), 262.

[4] Blight refers to W. E. B. Du Bois’s, “artful challenge to the hegemony of Lost Cause ideology.” Writing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, DuBois was certainly challenging the white supremacy of the period, but freed people had been doing this all along. Blight, Race and Reunion, 251.

[5] Richmond Dispatch, July 6, 1866. Kathleen Ann Clark, “Celebrating Freedom: Emancipation Day Celebrations and African American Memory in the Early Reconstruction South” in Where these Memories Grow: History, Memory, and Southern Identity, edited by W. Fitzhugh Brundage (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000): 107-132. See also Elsa Barkley Brown and Gregg D. Kimball, “Mapping the Terrain of Black Richmond,” Journal of Urban History 21, no. 3 (March 1995): 296-346.

[6] Joan Marie Johnson, “’Drill into us…the Rebel Tradition’: The Contest over Southern Identity in Black and White Women’s Clubs, South Carolina, 1898-1930,” Journal of Southern History 66, no. 3 (Aug. 2000), 531. There is certainly scholarship that has elevated these Black histories, in addition to Johnson’s work, see Kathleen Ann Clark, Defining Moments: African American Commemoration & Political Culture in the South, 1863-1913 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2005) and William H. Wiggins, O Freedom! Afro-American Emancipation Celebrations (University of Tennessee Press, 1990).

[7] Blight, Race and Reunion, 369.

[8] Richmond Planet, May 10, 1890, 1.

[9] Reprinted in Richmond Planet, June 7, 1890, volume 7, page 2.