During the summer of 1776, members of Virginia’s last Revolutionary Convention adopted the Virginia Declaration of Rights. Among the principles of representative government and fundamental freedoms that it laid out was a clause that “all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of Religion, according to the dictates of conscience.” Since the colony’s establishment in 1607, the Church of England had been the only sanctioned church in Virginia and was supported by tithes that colonists were required to pay. The parishes and vestries were part of local government in the colony and were responsible for a variety of religious and civil functions, such as the care of orphans and poor residents and levying parish taxes. Dissenting denominations, including Presbyterians and Baptists, struggled for decades to achieve some measure of religious toleration. Members and clergy faced harassment, violence, fines, and even imprisonment. When Virginia’s General Assembly sat for the first time in October 1776, petitions began arriving from groups of dissenters in support of religious freedom requesting relief from religious taxation and an end to laws supporting the Anglican Church.

Evangelical denominations grew rapidly in Virginia during the 18th century and minsters often addressed large crowds outdoors. Ministers who did not obtain required licenses to preach were sometimes threatened, beaten, or jailed.

Engraving in A. S. Billingsley, LIFE OF GEORGE WHITEFIELD (1889).

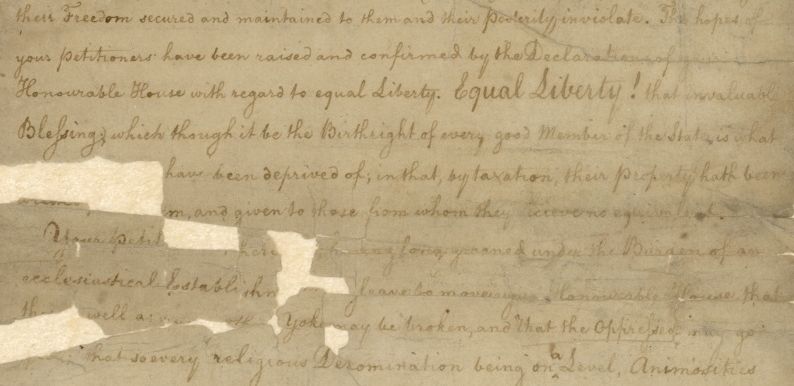

One such petition from “Dissenters from the Ecclesiastical Establishment, in the Common-wealth” arrived on October 16, 1776, and was “subscribed by near 10,000 Freemen.” Baptists in Virginia had organized a widespread petition drive calling for an end to all government interference in the practice of religion. “Having long groaned under the Burden of an ecclesiastical Establishment,” the signers demanded the separation of church and state so that “the Oppressed may go free” and every religious denomination would be on an equal level. Government should have no role in religious matters unless it was in support of “their just Rights and equal Priveliges.” Many copies of the petition circulated throughout Virginia and were signed primarily by Baptists, but also by members of other denominations. It was distributed by ministers in counties of the Shenandoah Valley, northern and central Virginia, and along the North Carolina border. Each page of signatures on the many copies of the petition were eventually fastened together in a long roll for presentation to the General Assembly.

The first page of the petition received on October 16, 1776, which included more than one hundred separate pages of signatures sewn together.

Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776–1865, Record Group 78, Box 366, Folder 13, Library of Virginia.

In response to the many petitions submitted in 1776, including the so-called “Ten Thousand Names Petition,” the General Assembly passed a law to exempt dissenting congregations “from contributing to the support and maintenance of the church as by law established.” Virginians no longer had to pay taxes to support the established church in Virginia, which was renamed the Protestant Episcopal Church after the Revolutionary War. But it took another decade of continuing pressure from dissenting Virginians for the Act for Establishing Religious Freedom, proposed by Thomas Jefferson in 1779, to be adopted into state law in 1786. This act had a profound influence on the language of the first amendment to the U.S. Constitution and on the meaning of religious freedom around the world.

Virginia’s 1786 Act for Establishing Religious Freedom was one of the most revolutionary pieces of legislation in American history. It made religious beliefs and practices private matters with which the state government could not interfere, and prohibited the exclusion of a person from holding public office as a result of their religious beliefs.

Records of the General Assembly, Enrolled Bills, Record Group 78, Library of Virginia.

The petition is available online through the Library of Virginia’s catalog. A transcription of the names on the 1776 petition has been published in volumes 35−38 of the Magazine of Virginia Genealogy.

Learn more about petitions for religious freedom in our In the Gallery video with Library of Virginia historian (retired) Brent Tarter.

The “Ten Thousand Names Petition” and other legislative petitions are in the Library’s current exhibition, Your Humble Petitioner, on display in the gallery until November 19, 2022. For more information, visit the exhibition website.