In 1987, the Richmond Times-Dispatch contemplated the future of local libraries thirty-eight years ahead, in the far-flung year of 2025. “There will still be books on the shelves,” the reporter assured readers, but there would also be “books stored on lazer disks…read from video display terminals.”1 The article was correct that there are still books on the shelves, lots of them, as well as the fact that we have electronic books – though they might not have been as popular if you had to read them from a terminal in the library.

News articles about libraries follow predictable patterns. One cliché is the article asking if libraries are becoming obsolete, and another is one seemingly surprised that libraries “have more than just books” to offer the public.2 Both of these articles fall for the same fallacy, that libraries are a place for books, when in fact libraries are a place for information. For this reason, they are often early adopters of new technologies that provide access to information in new ways.

For many centuries, books and documents have been the primary vehicle to share information and for this reason many libraries continue to offer books, but they have never been the exclusive method. Information can be visual and auditory in addition to written, and increasingly all these forms can be digital as well as physical.

Next year, the Library of Virginia will celebrate its two-hundredth anniversary. Through those years it has seen a great many technological advances that have changed how information is preserved and accessed. As a library and an archive, the staff not only have to keep informed regarding both past and present forms of media, but have to prepare for future ones as well.

At the start of any new organization, it can be a challenge to gain access to the current technologies, let alone the cutting-edge ones. For decades, the library fought battles to acquire enough space and shelving just to house its collection in a building free of rodents, mold, and asbestos.3 In 1940, the Virginia State Library (as the Library of Virginia was known at the time) moved from the current Oliver Hill Building to a building in Capitol Square between 11th and Governor Streets (now the Patrick Henry Executive Office Building). Its new home provided the latest advances in fire-proofing and spaces to take advantage of technologies not in existence when the former building was built, including a “micro photography lab” that could be used to create microfilm.4 By the time it moved again, in 1997 to the current building, those technologies were becoming outdated as well.

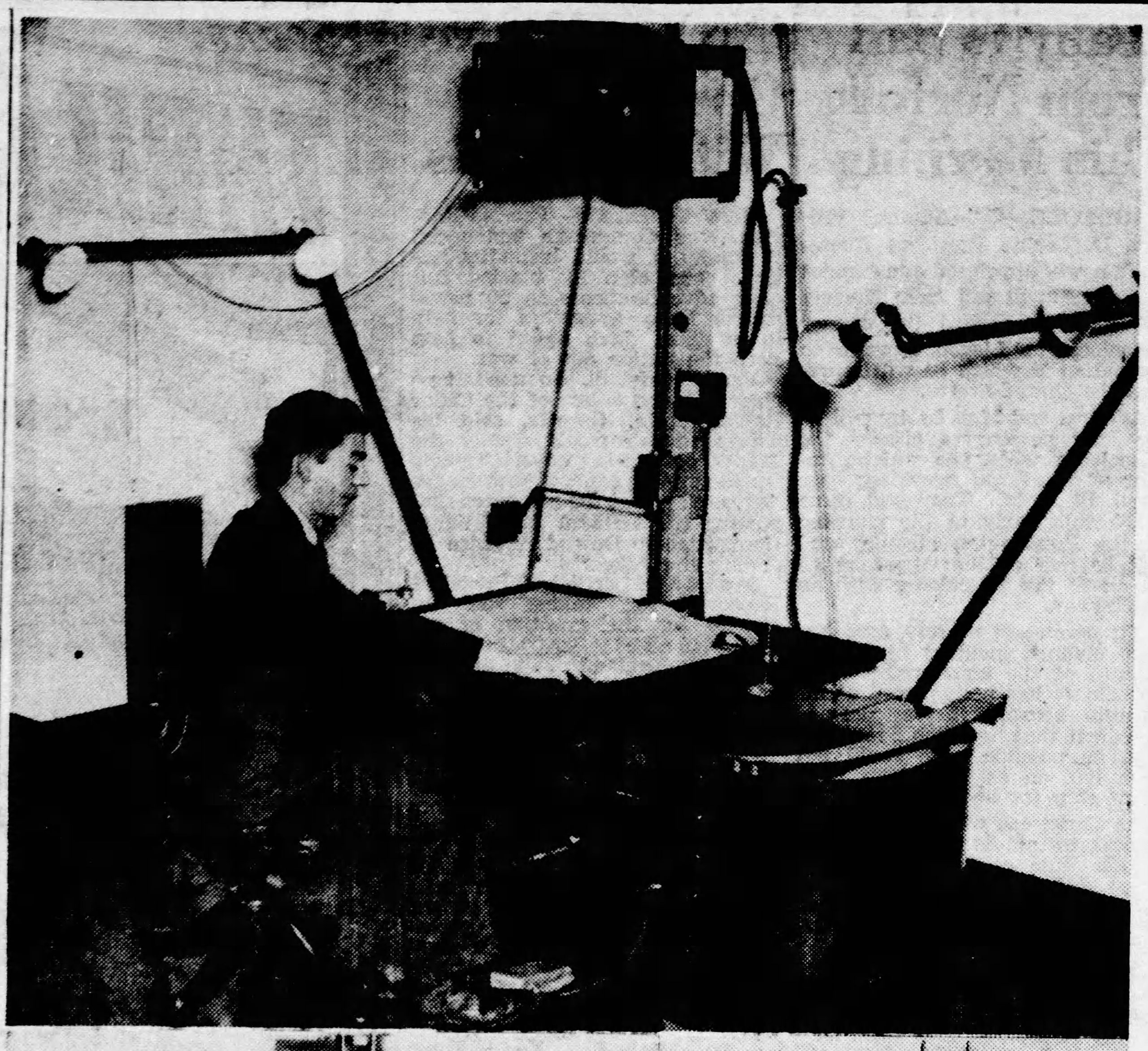

A precursor in many ways to digital scanning, microfilm (microphotographic images of documents on film viewed via a magnifying device) allows for a more portable and sustainable copy of the original item. Microfilm is no longer being produced at the same rate as in the past, but it is still used daily in many institutions around the globe, including LVA, though the machines we use to view it have become smaller and smaller.

RICHMOND TIMES-DISPATCH, 24 November 1996.

Both photography and videography were invented after the formal organization of the library in 1823, but as audio-visual information began to be an important aspect of everyday life (and therefore, the historical record) it quickly became part of the library’s collections as well. The first dedicated “picture librarian” was hired in 1959 to oversee what is now our visual studies department.5 In the 1970s, the state library maintained a lending library of over 2,000 16mm-film reels; now we have a YouTube channel.6

As computer processing and digital technologies have progressed, both the types of information storage devices that have to be preserved, and the ways we can interact with information preserved on them, have proliferated. Archivists at LVA and other institutions in recent years have had to learn how to both preserve and present information that is “born-digital,” such as the gubernatorial records of the Kaine and Northam administrations. But these challenges have also provided new ways to look at the historical information.

Embracing new technologies is not always smooth-sailing. The creation of a downtown power station in the 1920s meant to bring electricity to many state buildings wreaked havoc on both artifacts and archivists alike as it vibrated the entire library building.7 A 1945 Richmond Times-Dispatch article praises the state library for hosting instructive classes on the “Barrow method,” a now discredited technological leap in preservation that called for laminating documents. Preserving not only the materials themselves, but the records of our past practices and mistakes, makes certain we will be better prepared for the next 200 years.8

Join us online on Tuesday, December 20th as the Common Ground Virginia History Book Group discusses The Age of Astonishment: John Morris in the Miracle Century—From the Civil War to the Cold War by Bill Morris. The author traces how the technological advances of 1864 to 1955, the years of his grandfather John Morris’s life, shaped both the history of this country and the lives of its citizens.

Footnotes

- “The Library of the Future.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 22 March 1987.

- Griffin, Alison. “Libraries Are No Longer Just a Place for Books.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 16 February 1975.

- Robertson, Gary. “Library to Close Chapter.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 24 November 1996.

- “State Library Priceless Documents To Microfilm for Permanent Records.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 23 December 1940.

- Duke, Maurice. “Librarian Looks Back on Three Decades.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 20 July 1975.

- Duke, Maurice. “State Library’s Film Collection Serves Entire Commonwealth.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 23 February 1975.

- “State Library Building Suffers Palsy Attack; May Take Action.” The News Leader (Richmond, VA), 30 April 1924.

- “Latin-American Archivists Study State Library Methods.” Richmond TImes-Dispatch, 22 November 1945.

Resources

Born in 1863, John Morris lived through an “Age of Astonishment” defined by rapid technological and social change. Below are biographies of eight Southerners, also born in 1863, who left their mark on Morris’s world.

Simon Flexner (1863–1946)

Physician and scientist, born in Kentucky

- Flexner, James Thomas. An American Saga: the Story of Helen Thomas and Simon Flexner. Boston: Little, Brown, 1984.

- Simon Flexner (National Academy of Sciences)

John Luther “Casey” Jones (1863–1900)

Railroad engineer and folk hero, born in Kentucky

- Casey Jones (Mississippi Blues Trail)

Adella Hunt Logan (1863–1915)

Educator and activist, born in Georgia

- Alexander, Adele Logan. Princess of the Hither Isles: A Black Suffragist’s Story from the Jim Crow South. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

- Adella Logan Hunt (New Georgia Encyclopedia)

Helen Dortch Longstreet (1863–1962)

Newspaper editor, librarian, and activist, born in Georgia

- Helen Dortch Longstreet (Georgia Women of Achievement)

John Mitchell, Jr. (1863–1929)

Newspaper editor, politician, and activist, born in Virginia

- Alexander, Ann Field. Race Man: The Rise and Fall of the “Fighting Editor,” John Mitchell, Jr. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002.

- John Jr. Mitchell (Encyclopedia Virginia)

Mason Patrick (1863–1942)

Chief of the U.S. Air Service, born in West Virginia

- White, Robert P. Mason Patrick and the Fight for Air Service Independence. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001.

- Major General Mason M. Patrick (US Air Force)

Amélie Rives (1863–1945)

Author, born in Virginia

- Censer, Jane Turner. The Princess of Albemarle: Amélie Rives, Author and Celebrity at the Fin de Siècle. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2022.

Lucey, Donna M. Archie and Amélie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age. New York: Harmony Books, 2006. - Amélie Louise Rives Chanler Troubetzkoy (Dictionary of Virginia Biography)

Mary Church Terrell (1863–1954)

Educator and activist, born in Tennessee

- Cooper, Brittney C. Beyond Respectability : the Intellectual Thought of Race Women. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

- Quigley, Joan. Just Another Southern Town : Mary Church Terrell and the Struggle for Racial Justice in the Nation’s Capital. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Mary Church Terrell (VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project)