Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of blog posts regarding Virginia female newspaper editors by our Transforming the Future of Libraries and Archives Intern for 2023, Elena Cario. Elena is majoring in English at Christopher Newport University. She is working with the Library’s Virginia Newspaper Program. Keep an eye out for the next installments in the coming months.

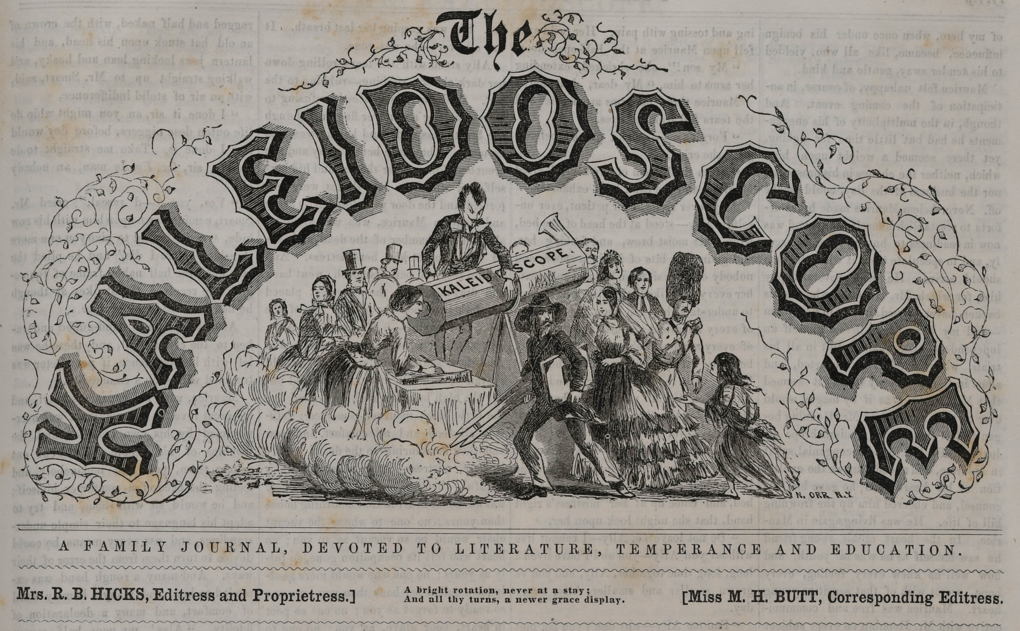

Using the power of her pen, Mrs. Rebecca Broadnax Hicks, editor of the Petersburg newspaper, the Kaleidoscope, spoke boldly about gender discrimination and progressive ideas for women decades before it was popular to do so. The Kaleidoscope ran from January 17, 1855 until early 1857, during which time Hicks faced much backlash from male editors while raising awareness about gender inequality, education, temperance, and literature.

Literature was a major part of the Kaleidoscope, and Hicks herself authored serialized novels she published in the paper in 1855 and 1856. Even before the birth of the Kaleidoscope, Hicks had already published two novels, The Lady Killer in 1851 and The Milliner and the Millionaire in 1853. She also published poems, short stories, essays, and biographies by both men and women in the literature section of the Kaleidoscope.

Hicks’s periodical also voiced her progressive thoughts about gender equality and how women should go about obtaining the rights they deserve. “[Rebecca] deeply resented the concept that women were the intellectual inferiors of men,” explains Barbara Browder’s Our Remarkable Kinswoman, an unpublished manuscript in the Dictionary of Virginia Biography research files at the Library of Virginia. Browder goes on to say that Hicks wanted “to be recognized as having an intellectual capacity at least equal to that of most men.”1

Hicks wrote insightfully about discrimination in its varied forms, with discussions of general women’s rights, female education, and the rights of domestic women. She began sharing her ideas in the fourth edition of the Kaleidoscope under the heading “Woman’s Rights – A Chapter for the Women of Virginia, with a word now and then for the Men” and she did not stop until the paper’s conclusion in 1857. “That the sole object of a woman’s life is not fashion, dress, establishments, and matrimony,” wrote Hicks, “I sincerely hope the nineteenth century will triumphantly prove.”

While promoting equality, Hicks emphasized the idea that women should not act in a more masculine way to gain the respect and rights they innately deserved. “There is a womanly way to prove our great mission upon earth,” she wrote in the February 7, 1855 issue, “which these masculine women will never discover. So as long as we are women, we must act as such. We can never make men of ourselves; and it is our duty to endeavor to attain unto the perfect stature of Heaven’s last best gift, Women.” Hicks used the biblical story of Adam and Eve to emphasize her point that women must “please the men, before we can ever hope to conquer them.” She claimed that Eve could never have forced Adam to eat the apple, but she asked him “[in] such a womanly bewitching manner that Adam could not find it in his loving heart to refuse.”

Many of her male counterparts believed that Hicks’s husband, Dr. Benjamin Hicks, did not support his wife’s position as “editress” of the Kaleidoscope. To dispel the rumors, Dr. Hicks wrote a “special notice” that his wife included as a regular entry in the paper. Emphasizing that he did in fact support his wife as editor, Dr. Hicks explained “that she never could have occupied it without his consent,” and “if those who profess to be his friends would remember that nobody can be a friend of him who is not a friend to his wife.” The special notice appeared in every issue from May 2, 1855 until July 11, 1855.

Hicks’s role as an editor was an important part of her identity, and she hoped to empower other women through her words. “Hicks understood that her unusual occupation as an editor provided a public forum for expressing opinions unavailable any other way,” Jonathan Daniel Wells explains in his work Women Writers and Journalists in the Nineteenth-Century South, “and she referred to her status as a journalist often. In Hicks, the political power and intellectual freedom of editorship was the vital platform for denouncing gender discrimination.”2 Rebecca Broadnax Hicks did not take her voice for granted, but that is not to say she did not experience sexism as editor of the Kaleidoscope.

Despite her husband’s defense, Hicks still experienced adversity from fellow publishers. She was not invited to an editorial convention hosted in Richmond in November of 1855. Soon after, in the 44th issue of the Kaleidoscope, Hicks “criticized the ‘awful conclave’ for its secrecy and for leaving her out, claiming that perhaps the editors should be classed with the same fraternity of ‘Free Masonry, Odd-Fellowship, and Know-Nothingism.’”3

Recognizing today that Hicks’s words were not those of dreams but of future change, is inspirational. Women did not get the right to vote until 1920, 65 years after her first column on women’s rights and 63 years after the Kaleidoscope was discontinued. By boldly questioning gender equality – unusual for a woman of her time – Rebecca Hicks brought society’s discrimination against women to light and contributed to the growing women’s rights movement, despite the fact that Hicks herself was not a direct participant in that movement.

The Library of Virginia could not have learned so much about Rebecca Hicks without the graciousness of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture. They generously allowed the LVA to borrow the only known originals of the Kaleidoscope, which will soon be added to Virginia Chronicle, the LVA’s digital newspaper database.

Hicks did not see her ideas become a reality as she passed away shortly after the Civil War in 1870, but her legacy lives on in the Kaleidoscope.

Footnotes

[1] Barbara B. Browder, “’Our Remarkable Kinswoman,’” unpublished typescript manuscript (1988), copy in Dictionary of Virginia Biography research files, Library of Virginia, 43.

[2] Jonathan Daniel Wells, “Antebellum Women Editors and Journalists,” Women Writers and Journalists in the Nineteenth-Century South, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, 2013, 116.

[3] Wells, 116.