In today’s society, we are all familiar with the concept of multifactor authentication to enhance security and to protect against fraud. Historically, this was also an important issue, but these individuals didn’t have facial recognition software, fingerprint scanners, or authorization codes. However, they still had to transact business and ensure that their documents were legitimate. There were several different techniques used to authenticate documents, many of which are still in use today. In the Archives Reference Department, we help researchers find records that document their ancestors and uncover a more complete story of their lives.

When researchers come to the Library of Virginia to view deeds, wills, and other court records, in most instances they are looking at the recorded copy. This copy was transcribed from the original document by the court clerk into the official record book that was held at the courthouse. When individuals showed up at the courthouse with a document to be recorded, however, there were steps taken to authenticate or prove that the document was legitimate. Not all these loose records survive; in some cases they were returned to the individual after being recorded, but some were kept by the court clerk.

On most of these documents there will be two separate dates. The first date in the body of the document is the date that the document was initially written. The second date, usually at the bottom or on the back, is the date that it was proved or authenticated in court and recorded. The Library of Virginia even has some collections of local records that were not successfully authenticated, those being described as unrecorded deeds or unproven/partially proven documents.

When you look at historical records, there are several ways that documents could be authenticated.

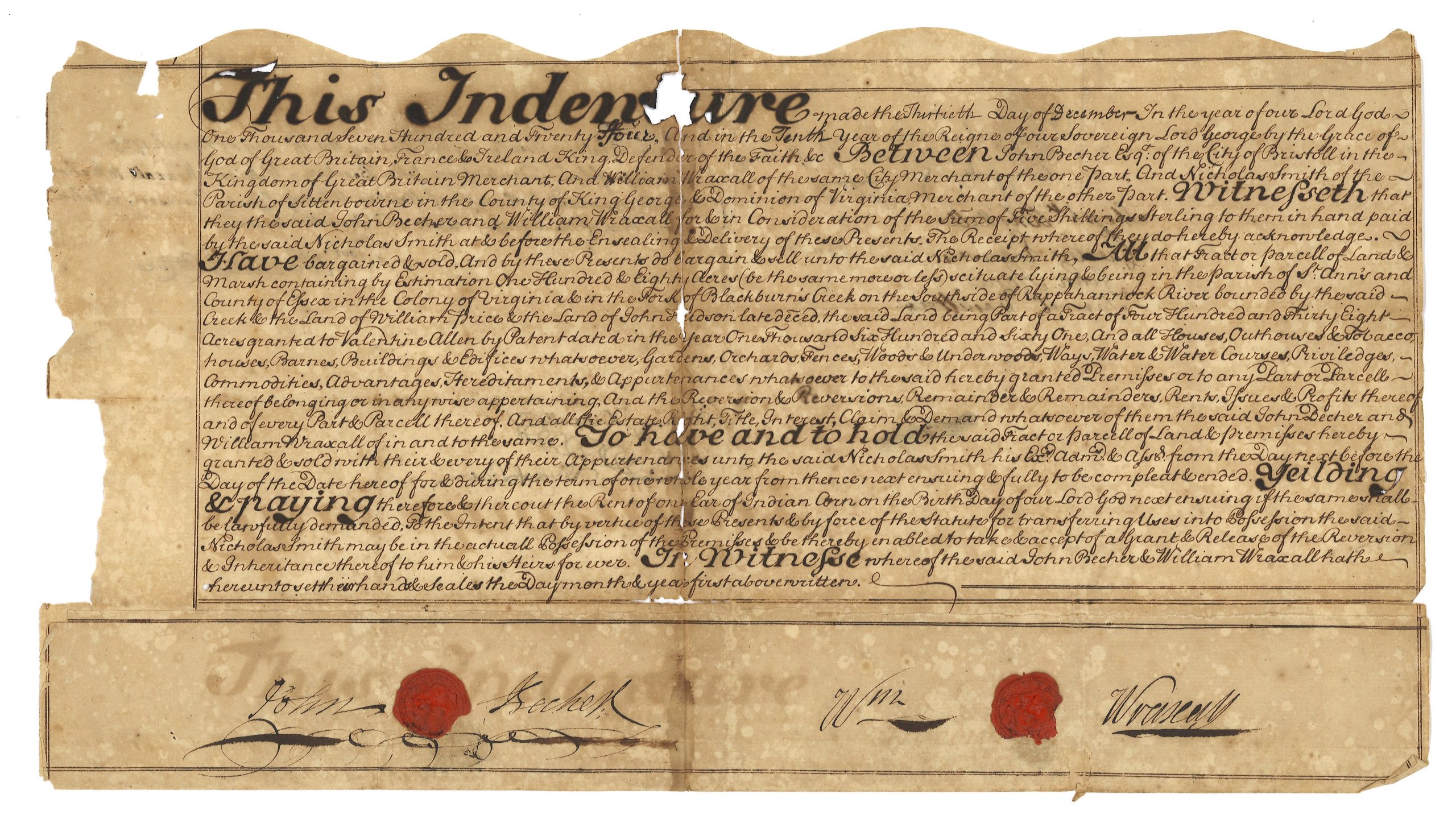

- Signatures – Both people in the past and current researchers often compare signatures with other documents that they know belong to an individual to determine if the document relates to the same person. In some cases, it could be someone else with the same name, or possibly a forgery. (Figures 2, 5, 6)

- Marks – Many people were illiterate during this period, so if they could not write their name, they made “their mark” on the legal document. In some cases, this is just an “x” but many individuals created a unique mark. (Figure 1)

- Witnesses – The testimony of witnesses is still important today; in the 18th century, witnesses could attest to the validity of a document by familiarity with the handwriting of the individual or being present when the document was initially drawn up and signed. In fact, many of the loose documents in the Library of Virginia’s collection that are “partially proved” were set aside while waiting on additional listed witnesses to come to court and authenticate the document such as Example four below. (Figures 3,4,5,6)

- Seals – The presence of official wax seals is an easy way to determine if the loose record is an original document. (Figures 3,5,6,)

- Indentures – This is the most interesting process of historical document authentication. Technically, an indenture can be any type of contract between individuals, although it has become synonymous with indentured servitude in the colonial period. In many cases there were two identical copies of a document written on one piece of paper and then cut apart in a unique “indented” pattern. If necessary at a later time, the two pieces could be put back together in order to prove it was the same original document. (Figures 2,4,5,6)

These documents are a fascinating look at how individuals historically authenticated documents in order to execute contracts and conduct business in the 18th century.