Fall is in the air and Pumpkin Spice is everywhere (that includes my coffee). It’s October, the month of Halloween! I loved Halloween as a child. For many years I chose to be a witch for Halloween. Why? They were scary, green, got to wear black every day, and quite possibly owned a few flying monkeys. . .

Now, as an adult I love a good haunting story. I love learning the folklore formed from local history. One such witchy story hails from the former Lower Norfolk County, later becoming Princess Anne County, now Virginia Beach. The witchcraft case of Grace Sherwood is the most famous in Virginia history.

We have all heard of the Salem Witch trials where hearings and prosecutions of around 200 people accused of witchcraft caused hysteria amongst the Puritans in colonial Massachusetts between 1692 and 1693. Less recognized are the Virginia witches.

English Parliament passed “An Acte against Conjuration Witchcrafte and dealing with evill and wicked Spirits” in 1604. It was this act that the Virginia colonial government used to prosecute those accused of withcraft. Part of the law reads,

be it further enacted by the authoritie aforesaide, That if any pson or persons, after the saide Feaste of Saint Michaell the Archangell next cominge, shall use practise or exercise any Invocation or Conjuration of any evill and wicked Spirit, or shall consult covenant with entertaine employ feede or rewarde any evill and wicked Spirit to or for any Intent or purpose; or take up any dead man woman or child out of his her or theire grave, or any other place where the dead bodie resteth, or the skin bone or any other parte of any dead person, to be imployed or used in any manner of Witchcrafte Sorcerie Charme or Inchantment;1

The first recorded case of a person accused of witchcraft in colonial Virginia based on this law was that of Joan Wright of Surry County in September of 1626. The case was heard by the Council and General Court of Virginia in Jamestown. Accusations ranged from cursed livestock, foul crops, heavy rainfall, spelled butter churns, accurate predictions of deaths of persons she knew, and a newborn’s death. Wright never disputed the charges and gave affirmation that some of the charges were indeed true. When told of her charges she said, “God forgive them.” Unfortunately, court records do not discuss how the hearing concluded. There are no surviving records of a sentencing. The case seemed to have never resolved and Joan Wright was possibly acquitted of the crime.2

In the case of Grace Sherwood of Pungo in Princess Anne County, growing hysteria was never an issue. The early Virginia courts seemed to try to discourge witchcraft charges, as they were bothersome and time consuming. Many times, the courts fined people for slander, rather than deal with a drawn-out examination and trial.

Little is known about Grace Sherwood prior to 1698, with the exception that she was considered a healer and midwife. She had three children with her husband. In September of that year, Grace’s husband, James Sherwood, sued their neighbors, John and Jane Gisburne and Anthony and Elizabeth Barnes, for slander. The Gisbournes claimed that Grace Sherwood had bewitched their pigs and their cotton, while the Barnes claimed that she rode Mrs. Barnes during the night and “went out the keyhole or crack of the door like a black cat.” The cases were dismissed.3

Grace Sherwood places assault charges on Luke Hill and his wife, Elizabeth.

In September of 1701 Grace Sherwood’s husband James died. Grace would never remarry. Her problems with her neighbors seemed to escalate after her husband’s death. By December of 1705, Grace Sherwood sued her neighbors Luke and Elizabeth Hill for assault. She won the case and received twenty pounds.

As if in retaliation, Luke Hill went back to court in January of 1706 and charged Grace Sherwood of witchcraft.4 It seems that these charges would set the stage of how the Princess Anne court would play out the Witchcraft Act of 1604.

As of February, the court decided that a jury of women would decide Sherwood’s innocence. The women stated that they found two witch marks on her body and the court ordered her to be jailed, however, the case never went to trial.5

Donation Farm Manor House; Princess Anne County; Associated with Grace Sherwood Who Was Ducked in Adjacent Waters, 1920.

Portsmouth Olde Towne photograph collection, part of the Portsmouth Public Library photograph collection.

That same year, on April 15th, the Colonial Council in Williamsburg, received word of Luke Hill’s petition of suspecting Grace Sherwood of witchcraft. The Princess Anne court petitioned the council to provide a recommendation on how to proceed with the judgment, at the same time, trying to appeal the case to the higher court. At the recommendation of Stevens Thomson, the Attorney General, the Princess Anne County court was told that they provided too general of an accusation and that the county court “ought to have made a Fuller Examination” and pursuant to the law, remanded her to the general prison of the colony.6 The council inevitably returned the case back to the lower court.

By 2 May 1706, the Princess Anne court reported the opinion of the council and decided to search the premises of Grace Sherwood’s home “for all Images & such like things as may any way strengthen the suspicion.”7 The evidence against Sherwood was presented in June of 1706 and at that time decided that she would be ducked (meaning she would be thrown into the water while her hands and feet were bound) by her own consent8. The court held off the ducking initially because “the weather being very rainy & bad soe yt possibly might endanger her health.”9 Sherwood consented to her punishment.

Bad weather day for a Ducking.

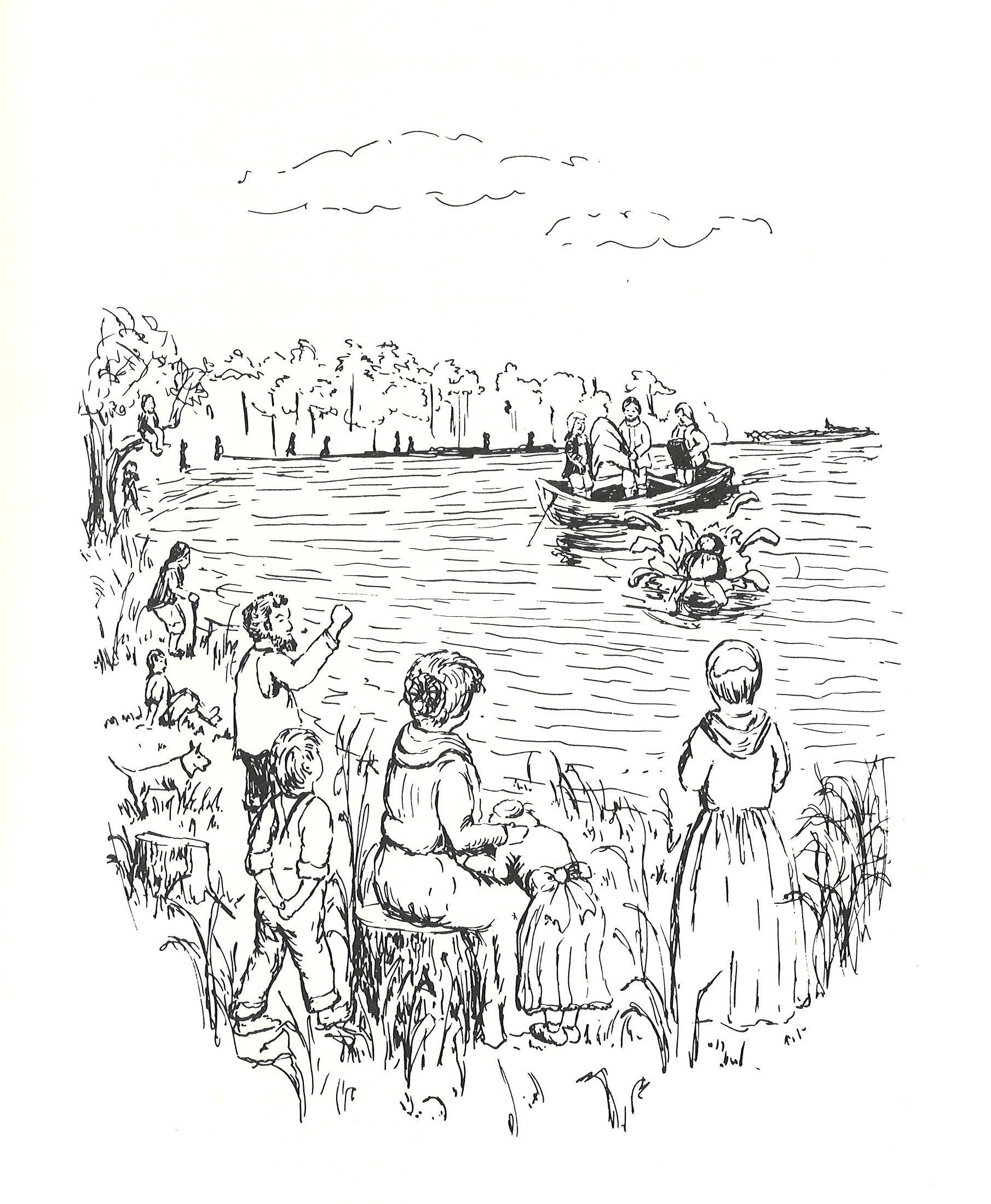

On the day of 10 July 1706, she was ducked on a branch of the Lynnhaven River near John Harper’s plantation. Interestingly, the court made note that they “always having care for her life to preserve her from drowning” and that other women would be on hand to search her body a second time for more witch marks. As it turns out, Sherwood floated. Her hands were said to have gotten free from their bindings and she was able to swim. She was searched again by a team of women, then remanded to the county jail to await another trial.10 The site at which she was thrown in the water is now named “Witchduck Point.”

No record of a second trial seems to exist. Court records show that Sherwood went before the county court in 1708 to pay a debt, leading one to believe that she had been freed from jail prior to that. By 1714, Sherwood petitioned for her landholdings be returned to her.11 Grace Sherwood died in or around 1740, as her will was probated that same year.12

Because so much is not truly known about Grace Sherwood and her life, tales have been woven throughout the years. One such popular children’s book was written in 1973 by Louise Venable Kyle, entitled The Witch of Pungo. The book written as a children’s short story with illustrations, recounts Sherwood’s sentencing through the eyes of two children.13

In an effort to clear Grace Sherwood’s name many individuals have researched her case. One such researcher, Belinda Nash, has studied Sherwood’s case extensively. At her urging, Virginia Governor Tim Kaine agreed to informally pardon Grace Sherwood after 300 years in July of 2006. The ceremony took place at Ferry Plantation House, where local re-enactors dress in costume to interpret and teach the historic significance of the event to the public. The letter of pardon sent by Governor Kaine was read to the public by the Mayor of Virginia Beach, Meyera Oberndorf.14

A statue of Grace Sherwood was unveiled on the lawn of the Bayside Hospital in Virginia Beach in April of 2007. The pedestal recognizes Grace Sherwood as “one of our first healers.”15 The Virginia Department of Historic Resources placed a marker K-276 at Witchduck Point citing the Testing of Grace Sherwood in 2002. The place of her watery test and the adjacent land are named Witch Duck Bay and Witch Duck Point.16

Was she really a witch or was Grace Sherwood a target for scorn in the community? Many are of the latter assumption that her gender, her role as a healer, and her independence as a widow may have stoked jealousy amongst those who chose to slander her. To quote former Governor Tim Kaine, “with 300 years of hindsight, we all certainly can agree that trial by water is an injustice” and “women’s equality is constitutionally protected today, and women have the freedom to pursue their hopes and dreams.” I’m sure Grace Sherwood’s dream was to live a simple quiet life after her great ordeal, which as far as we know, she did.

As for me, I still occasionally dream of being that scary black clad, green tinged, flying monkey handler, known as a witch.

Footnotes

[1] Encyclopedia Virginia, ““An Acte against Conjuration Witchcrafte and dealing with evill and wicked Spirits”(1604), https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/an-acte-against-conjuration-witchcrafte-and-dealing-with-evill-and-wicked-spirits-1604/

[2] H. R. McIlwane, ed., Minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia 1622–1632, 1670–1676 (Richmond: Library of Virginia, 1924), 111–112. Encyclopedia Virginia, “General Court Hears Case on Witchcraft” (1626), https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/general-court-hears-case-on-witchcraft-1626/

[3] Princess Anne County, Order Book 1, 1691-1714, Reel 38, p. 178.

[4] Ibid., p. 426.

[5] Ibid., p. 428-429; p. 431.

[6] Virginia Colonial Papers, Proceedings of the Council, 1706 Apr. 15, Miscellaneous Reel 610, Accession 36138, 1p.

[7] Princess Anne County, Order Book 1, 1691-1714, Reel 38, p. 439.

[8] Ducked meaning: Accuser’s hands and feet are bound and then thrown into a body of water to see if the accuser would float.

[9] Princess Anne County, Order Book 1, 1691-1714, Reel 38, p. 445.

[10] Ibid., p.445.

[11] Virginia Land Office Patents No. 10, 1710-1719, Reel 10, p. 179, Grace Sherwood, Princess Anne County, 145 acres.

[12] Princess Anne County, Deed Book 5, 1735-1740, Reel 5, p. 301, Will of Grace Sherwood, probated, 1 October 1740.

[13] Kyle, Louisa Venable., and Jan Dool. The Witch of Pungo, and Other Historical Stories of the Early Colonies. Virginia Beach, Va: Four O’Clock Farms Pub. Co., 1973. Print.

[14] Governor Timothy M. Kaine, Constituent Correspondence, 2001-2010 (bulk 2006-2009). Accession 44678, Box 23, Barcode 1204023, Letter, Tim Kaine to Belinda Nash, 10 July 2006. Located by Roger Christman and sent via email.

[15] Nash, Belinda . “The Witch of Pungo.” Grace Sherwood-The Witch of Pungo. January 25, 2009. www.carolshouse.com.

[16] Adams, Kathy, “What’s in a name? Virginia Beach’s Witchduck Road”. The Virginian-Pilot, 1 June 2009.