The Library of Virginia started accessioning business records in 1911. State Librarian Henry Read McIlwaine recognized the importance of such records. “From this source by itself it would be possible for a competent worker in such material to reconstruct accurately the business methods obtaining in Virginia … in fact, to set forth the whole economic condition of the people.”1 This blog post takes the reader through the process of identifying and contextualizing a 19th century ledger.

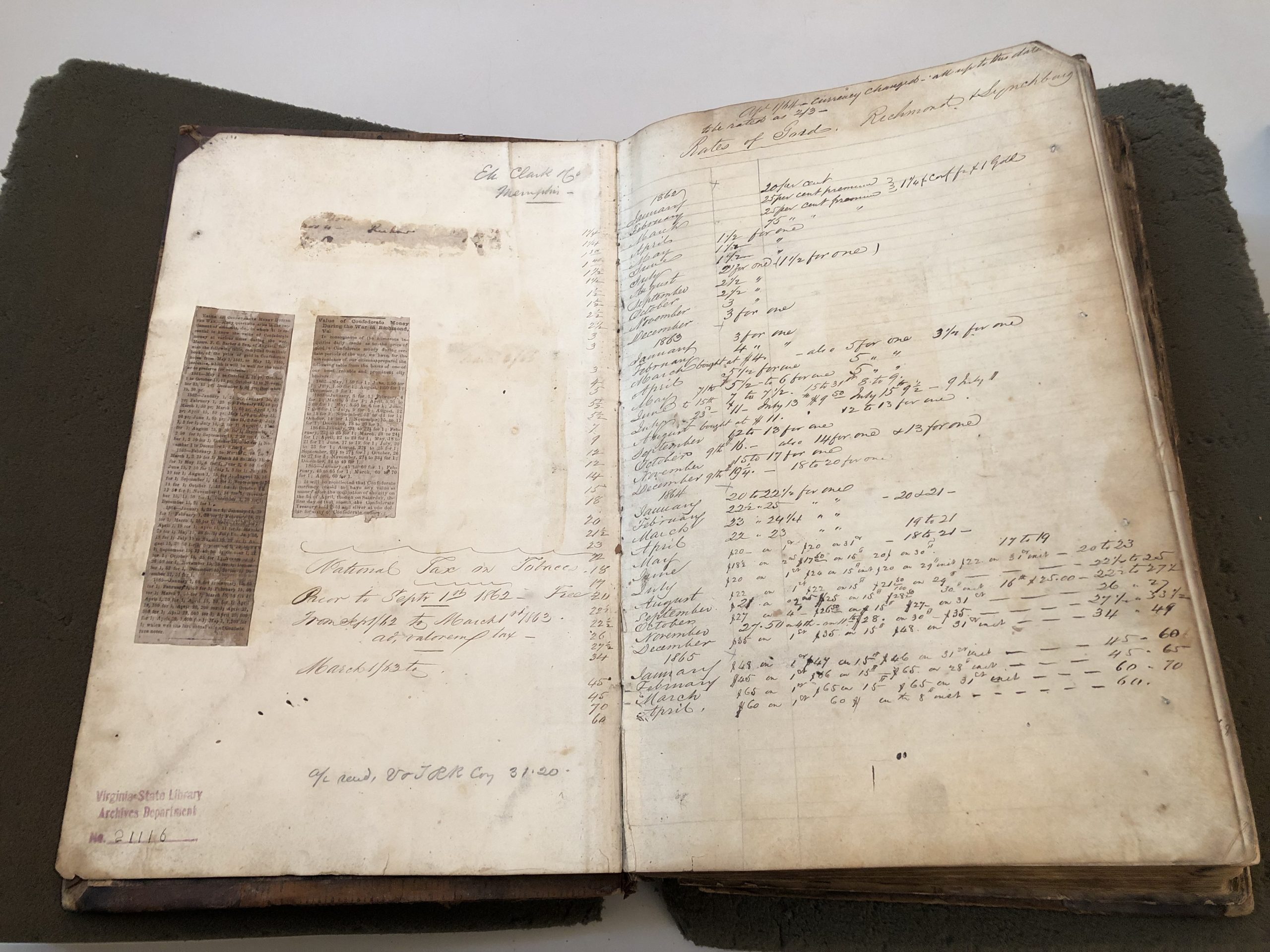

The Library purchased the ledger in question from the Around-the-Corner Book Shop in Lynchburg on September 9, 1936. The binding is broken and deteriorating, but the 700 pages are intact. The accession analysis notes that it contains “routine business entries” of “an unidentified merchant, Lynchburg, Virginia.”2 The entries cover two periods. The first is from August 1832 to January 1837. The second is from January 1865 to December 1867. The catalog record notes that it includes “monthly accounts for customers’ purchase of dry goods, groceries, liquor, hardware, and other sundry goods. Also notes charges on notes, bonds, and interest.”3

A close reading of the ledger reveals that it belonged to not one merchant but several, and includes not only business records, but also personal financial records. Checking advertisements in the Lynchburg newspapers, which are available and searchable on VirginiaChronicle.com, was the ideal place to start the search for the owners of the ledger.

The entries from 1832 to 1837 are from the firm of L. & R.B. Norvell. Lorenzo Norvell (1801-1880) and Reuben B. Norvell (1809-1884) established their business following the death of their brother George R. Norvell (1796-1828). Previously, George and Lorenzo were partners in the firm of G.R. & L. Norvell.4 When George died in 1828, he specified in his will that Lorenzo and Reuben were to operate the original business (G.R. & L. Norvell) for four years, after which they were to pay each of George’s legatees their portion of his estate.5 Four years later, after those stipulations were met, the firm officially became L. & R.B. Norvell, with the first ledger entry beginning in August 1832, four years after George’s death.

The entries frequently include transactions with John Caskie (1790-1867), a successful tobacco merchant and one of the most influential men in Virginia, who had married the Norvells’ sister Martha Jane Norvell (1797-1844).6

The transactions begin as Lorenzo and Reuben Norvell settle their brother’s estate. One of the transactions records Reuben’s purchase of “Maria and her two children” for $500 from the estate. The sale was routine for the Norvells, but anything but for Maria. Frederic Bancroft, in Slave Trading in the Old South (1931), describes the depravity of the auction block. “When young women were on the block the auctioneer often indulged in broad humor or suggestions that would have been considered indecent on almost any other public occasion.” 7

The Norvells had no apparent qualms about the slave trade. Lorenzo relocated to Baltimore in 1836 and advertised the sale of his 500-acre farm and “thirteen valuable slaves, six men, three women, and four likely boys; among them are both house servants and field hands of the most valuable descriptions.”8 Enslaved people from Lynchburg were often purchased by traders from Mobile and New Orleans. Lorenzo returned to Lynchburg and became cashier of the Lynchburg National Bank. When he died in 1880, the man who sold off men, women and children like livestock was eulogized as “a man of great dignity and force of character, of unblemished integrity, strong in his feelings, and unbounded in his principles of rectitude and honor.”9

The entries from 1865 to 1867 are from the firm of A.B. Rucker. For a quarter century before the Civil War, Ambrose B. Rucker (1813-1872) was a wholesale grocer, commission merchant, auctioneer, and a fixture in Lynchburg society. He was a founding member of the Court Street Methodist Church, a fundraiser for the relief of the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1855, and one of the founders of Spring Hill Cemetery.10 Entries in the ledger include the sale of plots in the cemetery. LVA also holds a letter of Rucker’s dated January 9, 1861, in which he reflects on the approach of the war. “The weather now is extremely bad – muddy streets and many dark clouds – with the political state of the country looking more and more threatening than ever – The expression of old preacher Robinson is particularly applicable just now – ‘the Devil turned loose’ – still hoping that some bright spot will appear soon on our political horizon.” 11

Rucker likely availed himself of the unused portion of the Norvells’ ledger due to paper shortages in the final months of the Civil War but, shortages aside, he made a fortune in commerce and financial speculation. He did business with Tardy & Williams, a Richmond firm that sold goods brought in through the Union blockade. He also kept a close eye on the price of gold.

Following the war, Rucker was faced with the task of collecting debts from customers who had a deficit of gold, silver and greenbacks, and a surplus of Confederate currency and bonds. The latter two remained in circulation for months after the fall of Richmond and the surrender of Lee. One of the entries records the account of the firm of Moss, Day and Bowman, whose debt amounted to $18,282.89 in Confederate currency or $4,051.37 in gold.

Placed in proper context, the ledger sets forth the cruel business methods and harsh economic conditions in Virginia from the Antebellum Era to Reconstruction. The ledger is accessible to the public in the Library’s Archives Research Room.

Footnotes

[1] Conley L. Edwards III, Gwendolyn D. Clark and Jennifer D. McDaid. A Guide to the Business records in the Virginia State Library and Archives. Richmond: Virginia State Library and Archives, 1994. vii.

[2] L. & R.B. Norvell and A.B. Rucker Companies (Lynchburg, Va.) Ledger, 1832-1867, Accession #21116, Library of Virginia, Accession Analysis #21116.

[3] L. & R.B. Norvell and A.B. Rucker Companies (Lynchburg, Va.) Ledger, 1832-1867, Accession #21116, Library of Virginia https://lva.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01LVA_INST/altrmk/alma990004945370205756

[4] Jeffersonian Republican, August 8, 1828

[5] Lynchburg, Will Book A, 1809-1831, Reel 18, p. 297-298, Will of George R. Norvell, proved August 4, 1828, Library of Virginia

[6] Lyon Gardiner Tyler, ed. Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography, Vol. IV. NY: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1915. 141

[7] Frederic Bancroft. Slave Trading in the Old South. Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1996. 112

[8] Political Arena, September 30, 1836.

[9] Staunton Spectator, March 23, 1880.

[10] Christian, W. Asbury. Lynchburg and Its People. Lynchburg, J. P. Bell company, printers, 1900. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/00004023/.

[11] Ambrose B. Rucker letter, January 9, 1861, Accession #51076, Library of Virginia https://lva.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01LVA_INST/altrmk/alma990016927900205756

Header Image Citation

Ledger Entry, Rates of Exchange. Click to View Full Image.