The first set of records from the Virginia Revolutionary Conventions, 1774-1776 collection are now available on the Library of Virginia’s Digital Collections Discovery site. The collection contains the records of five state conventions that met prior to the creation of a new state government in 1776. The first convention was held at the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg on May 30, 1774. Twenty-five members of the House of Burgesses gathered to protest the closing of the port of Boston by British authorities as a punishment for the Boston Tea Party in 1773. The convention met in open defiance of Lord Dunmore, the royal governor, who had earlier dissolved the House of Burgesses. The members expressed their support for Boston and called for the creation of a Continental Congress. The conventions continued to serve as an alternative government in Virginia through July 1776.

The records in the collection consist of petitions, journals, minutes, reports, correspondence, and resolutions. They illuminate Virginia’s efforts at self-governance during the first year of the Revolutionary War. The first set of records available online involve the convention’s election of delegates to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. They provide insight into their efforts to create and maintain an army to fight the British. They also demonstrated the convention’s effort to create an economy independent of Great Britain.

A few documents in the collection share how the convention’s decision to oppose Britain was not supported by all Virginians. A group of citizens in Princess Anne County sent a letter to the convention in which they declared their oath of loyalty to King George III. They were outraged that a group of “factious men … have violently and under various pretenses have usurped … the power of government.” The citizens swore to defend the dignity and crown of King George III against the traitorous efforts of the convention. The letter ends with a warning to the convention not to send troops into Princess Anne County for “we will defend the passes into our County and neighborhood to the last drop of our blood.”

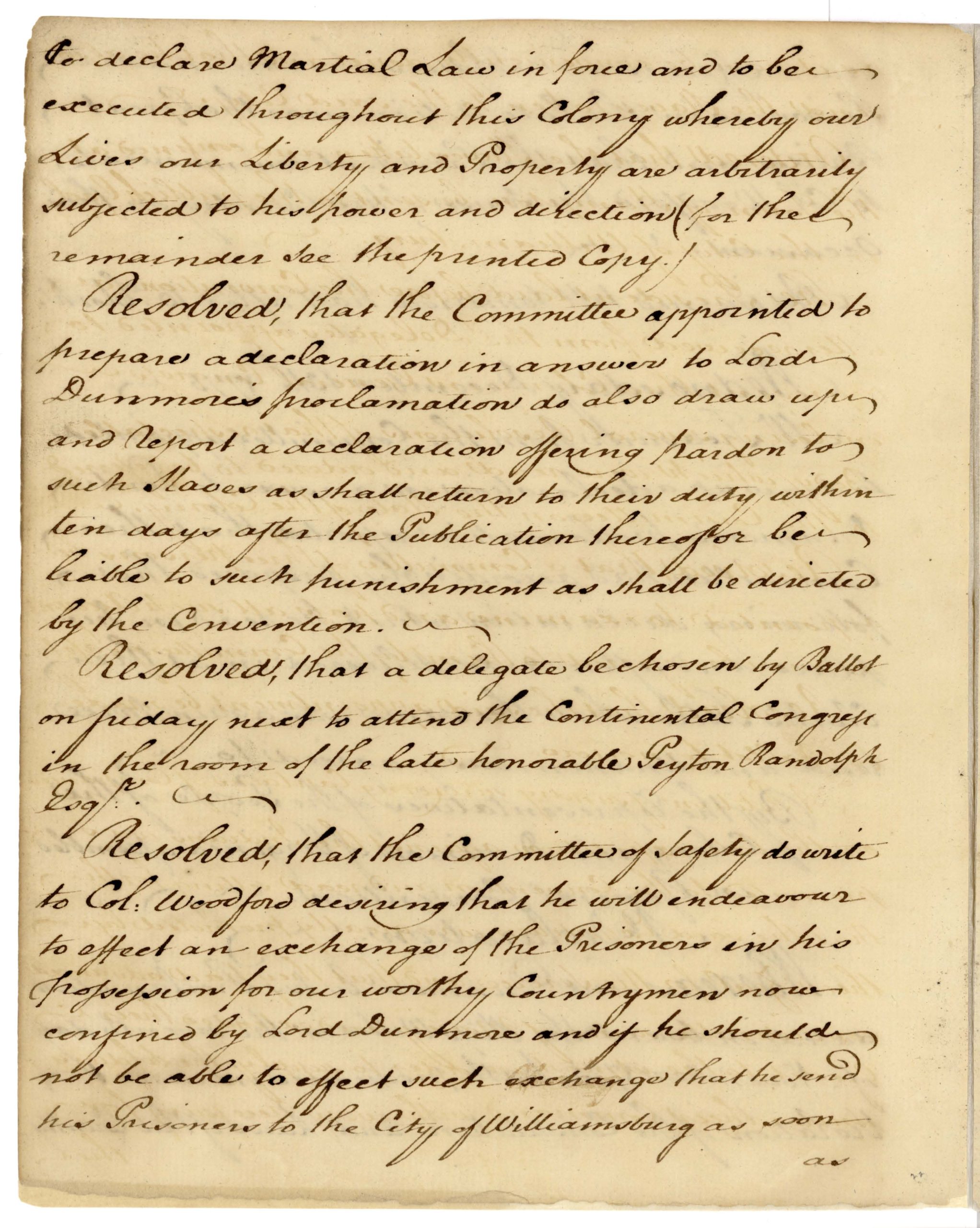

The records include the convention’s fierce criticism of Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation declaring martial law in the colony and offering freedom to indentured servants and enslaved people if they agreed to join the British army. The convention denounced what they deemed to be a threat to “our Lives, our Liberty and Property.” Dunmore’s Proclamation provoked the convention’s condemnation by not only raising the possibility of emancipating thousands of enslaved Black Virginians, but also arming them to fight against their enslavers. White Virginians had a long-held fear of an armed Black insurrection. Dunmore’s Proclamation stoked those fears. Due to their extreme anxiety over such an outcome, the rebelling colonists incorporated it into their list of grievances in the 1776 Virginia Constitution written by Thomas Jefferson. The convention accused Great Britain of “prompting our negroes to rise in arms against us.”

The convention’s perception of Dunmore’s Proclamation as a threat to “our Lives, our Liberty and Property” reveals additional unpleasant truths that have long been ignored. The word “our” was not inclusive but exclusive. The convention made it clear in their response that they believed that Dunmore’s Proclamation threatened the liberty of white Virginians. Liberty was not, in their view, meant for enslaved Black Virginians. Enslavement of Black Virginians was necessary to ensure the safety of white Virginians. And the use of the term “Property” reinforced the legal status of enslaved Black Virginians in the mid-eighteenth century. They were not human beings but possessions on the same level as cattle.

A report found in the convention records shares how five enslaved men in Accomack County, influenced by Dunmore’s Proclamation, pursued the liberty the convention claimed they should not have. They stole a ship in the middle of night and sailed to join Dunmore’s army and gain their freedom. Unfortunately, they were captured by colonial troops and placed in jail. One enslaved man was returned to his enslaver. The other four were sentenced to serve on the public works to build defenses against the British.

The convention ordered the enslavers of the four men to be paid annually out of public funds for the services of their “property.” A convention created to attain liberty denied five Black men their liberty.

Prior to scanning, the Virginia Revolutionary Conventions, 1774-1776 records were conserved to remove damaging cellulose acetate lamination that was causing the documents to degrade. Additional documents in the collection are currently being conserved. Once completed, images of the documents will be added to the digital collection.

The conservation work was generously supported by the following: Americana Corner, Ann McCauley Askew, Elizabeth Askew, Deborah Clayton and David McFaden, E. B. Duff Charitable Lead Annuity Trust, Friends of the Virginia State Archives, Genealogical Research Institute of Virginia, Georga S. Williams, Dr. Linda K. Miller, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, Order of Descendants of the Colonial Cavaliers, The Jamestowne Society, The Roller-Bottimore Foundation, The Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia, Virginia Law Foundation, Joyce and Bill Wooldridge, and many other individual donors.

If you would like to support this important preservation effort, you can make a gift online at www.lva.virginia.gov/donate or contact Elaine McFadden at elaine.mcfadden@lva.virginia.gov or 804.692.3592 to learn more about how you can help.