March 20th marks the centennial of Governor Elbert Lee Trinkle signing the Racial Integrity Act (RIA) into law. In simplistic terms, the RIA required every Virginian to identify their ethnicity on documentation that had to be approved by the Commonwealth of Virginia’s State Registrar.1 The legislation also defined who could be considered white and explicitly prohibited marriages between those white citizens and any other races.2 In order to understand how and why the RIA was passed in Virginia, we must investigate the political power and influence of John Powell, Earnest Sevier Cox, Dr. Walter Ashby Plecker, and the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America.

John Powell

John Powell, a classical pianist, composer, and self-declared expert on racial differences, was born on September 6, 1882, in Richmond, Virginia.3 His early career centered on composing, performing his compositions in the United States and Europe, and investigating and identifying American music.4 However, in the 1920s, Powell began to focus on the formation of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America with Earnest Sevier Cox and Dr. Walter Ashby Plecker.

Earnest Sevier Cox

Earnest Sevier Cox, a strong proponent of racial segregation and racial purity in Virginia, was born on January 24, 1880, near Knoxville, Tennessee.5 He received his bachelor of science from Roane College in 1899 and eventually attended the University of Chicago, where his racial beliefs evolved.6 Cox believed that Black people were inferior to white people and that the two races could not coexist in Virginia or the United States.7 In addition to studying racial relations in the United States, Cox took a five-year overseas trip to Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Singapore, the Philippines, Central and South America.8

After his travels, Cox moved to Richmond in January 1920 to sell real estate.9 In Richmond, Cox met John Powell, who held the same racial ideology as he did. Powell and Cox would work together to establish the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America. A third individual, however, used his position as a state official to further Cox and Powell’s racial ideals.

Dr. Walter Ashby Plecker

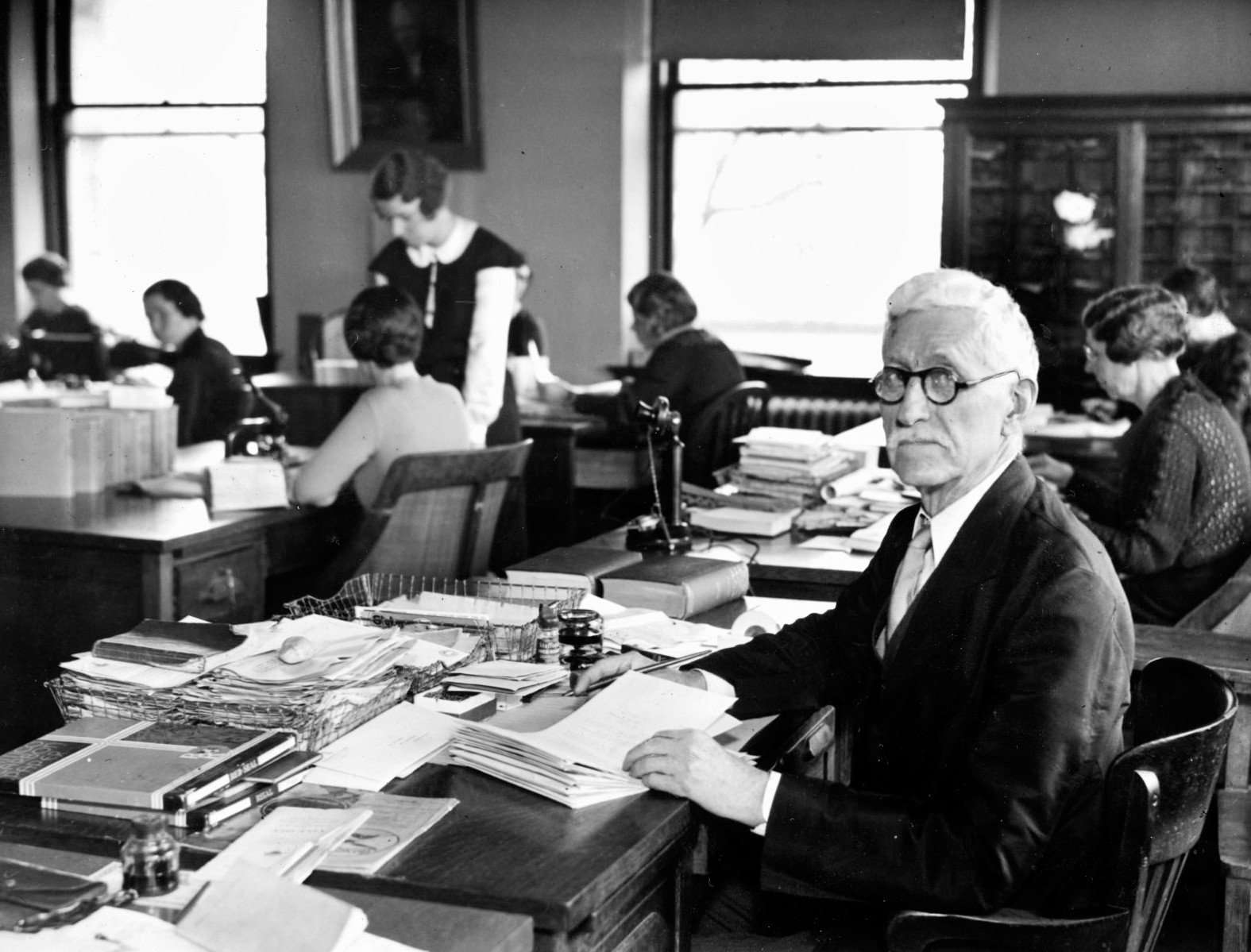

Dr. Walter Ashby Plecker of Augusta County was born on April 2, 1861. 10 After graduating from the University of Maryland Medical School in 1885, Plecker worked as a country doctor in western Virginia with a focus on maternal health, educating midwives, and decreasing the mortality of babies.11 He introduced the application of silver nitrate “to the eyes of newborns, a procedure that helped reduce incidences of syphilitic blindness.”12 On June 12, 1912, the Virginia legislature established the Bureau of Vital Statistics and appointed Plecker to be its first director and registrar. He would hold this position for thirty-four years until 1946.13 While his early medical accomplishments were explementary, his work for racial integrity and purity has forever tarnished his legacy in Virginia.

The Establishment of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America

The establishment of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America inaugurated a period in Virginia’s history where the pseudoscience of eugenics was used to categorize the citizens of the commonwealth, justify forced sterilizations, and push through legislation like the Racial Integrity Act. The term eugenics was coined by British naturalist and mathematician Francis Galton in 1883.14 In Galton’s opinion, eugenics was the “the study of the agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations, either physically or mentally.”15 Once the eugenics movement reached the United States, American advocates believed eugenics was the science “of the improvement of the human race by better breeding.”16 With these ideas and principles widely known, John Powell and Earnest S. Cox organized the Post No. 1 of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America (Anglo-Saxon Clubs) in Richmond in September of 1922.17 The mission of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs was “the preservation and maintenance of Anglo-Saxon ideals and civilization in America. In order to accomplish this purpose they pledged themselves to ‘strengthening the Anglo-Saxon instincts, traditions and principles…’”18 Additionally, Powell proclaimed that the Clubs were “now standing pledged to a work which means the salvation of the white race, the preservation of the blood integrity of the Anglo-Saxon race.”19 As historian J. Douglas Smith, author of Managing White Supremacy: Race, Politics, and Citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia, writes, “The Anglo-Saxon Clubs did not merely manipulate the racial fears and prejudices of whites but rather tapped into the assumptions that undergirded the entire foundation of white supremacy and championed segregation as a system of racial hierarchy and control.”20

To gain membership, potential members had to be “all native-born, white male American citizens, over the age of eighteen years, temperate habits and good moral character, who are qualified to vote or who will pledge themselves to qualify at the earliest opportunity.”21 The membership of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs typically came from the elite class of Virginia.22 The organization had chapters throughout the commonwealth as well as local colleges and universities. In 1923, one year after the formation of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America, The News Leader reported that the organization had over 400 members.23 By 1925, the organization had reached its peak and claimed to have “thirty-one posts in Virginia and three posts in the North including the University of Pennsylvania, Columbia University, and Staten Island.” 24

After the formation of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs, both Cox and Powell approached Dr. Plecker, now director and registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics, to become a member of their organization to lobby the General Assembly for the passage of legislation. As soon as Plecker became a member of the organization, he drafted the first version of the Racial Integrity Act.25 When the proposed legislation was written, Cox, Powell, and Plecker used the local Virginia newspapers to convince the wider public that the racial issues in Virginia needed to be addressed. Similarly, Cox and Powell traveled throughout Virginia giving speeches to anyone who would listen about the importance of racial separation and the need for the Racial Integrity Act.

Additionally, Powell utilized his musical performances to raise awareness for his racist cause. Relying on his “rare charm and magnetic personality,” he performed recitals of his Anglo-Saxonist folk-music and would finish by giving his audience speeches on the benefits of racial integrity.26 Powell would also encourage the formation of a woman-only organization similar to the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America, the Racial Integrity Women’s Club, which Powell would visit to stress the need for racial purity.27

The proposed Racial Integrity Act was introduced to the General Assembly as Senate Bill No. 219 on February 1, 1924, and followed by House Bill No. 311 on February 15, 1924.28 The Senate passed the proposed Racial Integrity Act on February 27, followed by the House on March 8.29 After many revisions, the final Racial Integrity Act stipulated:

“That the State registrar of vital statistics may as soon as practicable after the taking effect of this act, prepare a form whereon the racial composition of any individual, as Caucasian, Negro, Mongolian, American Indian, Asiatic Indian, Malay, or any mixture thereof, or any other non-Caucasic strains, and if there be any mixture, then the racial composition of the parents and other ancestors, in so far as ascertainable, so as to show in what generation such mixture occurred, may be certified by such individual, which form shall be known as a registration certificate.”30

From this opening section of the RIA, the General Assembly enacted legislation that would strictly categorize the commonwealth’s citizenry and explicitly define who was white. Page four of the Health Bulletin: The New Virginia Law to Preserve Racial Integrity, communicated that “the term ‘white person’ shall apply only to the person who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian…”31 For prominent Virginia families that traced their familial lineage through an Indigenous person or Pocahontas, the bulletin articulated, “… persons who have one-sixteenth or less blood of American Indian and have no other non-Caucasic blood shall be deemed to be white persons.”32 Therefore any person of any other ethnicity was classified as “colored.”

If any person was found guilty of providing false information regarding their ethnicity, that person would be charged with a felony and sentenced to one year in the state penitentiary.33 Following the signing of the Racial Integrity legislation into law, the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America expressed thanks to Governor Trinkle for his support. For Indigenous people living in Virginia, the Racial Integrity Act began a paper genocide that eliminated them from Virginia’s written records and continues to have a legacy lasting.

The author would like to thank Sophia Ciatti for contributions to this blog post.

Join us tonight, March 20th at 6pm, for a discussion on Virginia’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act, its impact on Virginia’s Indigenous communities and its long-lasting legacies. Dr. Gregory Smithers, professor of American history at Virginia Commonwealth University, will moderate the discussion with First Assistant Chief Wayne Adkins of the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, Chief Lynette Allston of the Nottoway Indian Tribe of Virginia, Assistant Chief Louise “Lou” Wratchford of the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe and Chief Robert Gray of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe. This talk is free and open to the public. Registration is required. Seating in the Lecture Hall is available on a first come, first served basis.

Footnotes

[1] “Virginia Health Bulletin: The New Virginia Law to Preserve Racial Integrity, March 1924,” 3.

[2] Brendan Wolfe, “Racial Integrity Laws (1924-1930),” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities. Last modified February 06, 2023, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/racial-integrity-laws-1924-1930/.

[3] “Forsaken: A Digital Bibliography,” in “Chapter 24: First Lady,” https://www.virginiamemory.com/online-exhibitions/exhibits/show/forsaken/firstlady.

[4] David Z. Kushner, “John Powell: His Racial and Cultural Ideologies,” 6. For more information on John Powell, see Richard B. Sherman’s article “‘The Last Stand’: The Fight for Racial Integrity in Virginia in the 1920s.”

[5] Douglas Smith, “Earnest Sevier Cox (1880-1966),” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities. Last modified June 22, 2022, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/cox-earnest-sevier-1880-1966/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Tori Talbot, “Walter Ashby Plecker (1861-1947),” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities. Last modified April 12, 2023, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/plecker-walter-ashby-1861-1947/.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Richard Sherman, “’The Last Stand’: The Fight for Racial Integrity in Virginia in the 1920s.” The Journal of Southern History, 54, no. 1 (Feb 1988): 71.

[14] Garland E. Allen, “The Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor, 1910-1940: An Essay in Institutional History.” Osiris 2 (1986): 225.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid, 225.

[17] Mika Endo, “Redefining Race: Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924 and American Indian Identification,” PhD diss., (George Mason University, 2022), 62.

[18] Ibid., 70.

[19] Blue Ridge Guide, April 17, 1924.

[20] J. Douglas Smith, Managing White Supremacy: Race, Politics, and Citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, 2002), 77.

[21] “Anglo-Saxon Clubs of American Application” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities., https://encyclopediavirginia.org/1569hpr-fc364d167b6fb1a/

[22]Ibid. 77.

[23] The News Leader, June 5, 1923.

[24] Endo, “Redefining Race,” 75.

[25] Ibid, 69-70.

[26] Altavista Journal, September 9, 1926. Wittney Skigen, “‘Not Negro Tunes at All?’ John Powell, Music, and White Supremacy in Virginia.” President’s Commission on the University in the Age of Segregation. University of Virginia, 2018. https://segregation.virginia.edu/not-negro-tunes-at-all-john-powell-music-and-white-supremacy-in-virginia-pavs-4500-student-paper-spring-2018/#_edn1.

[27] Virginia Union Farmer, September 30, 1927.

[28] Wolfe, “Racial Integrity Laws.”

[29] Ibid.

[30] “Virginia Health Bulletin: The New Virginia Law To Preserve Racial Integrity, March 1924,” 3, https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/dbva/items/show/226.

[31] “Virginia Health Bulletin,” 4.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.