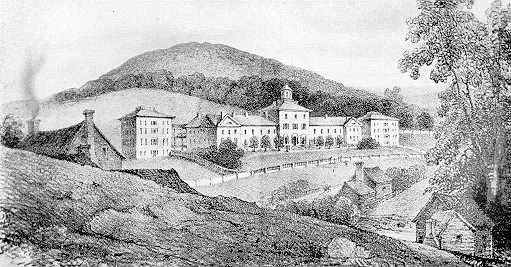

In 1883, the year when Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson solved the case of the Speckled Band, an equally baffling real-life killing drew another noted team of detectives to the Western Lunatic Asylum (later renamed the Western State Hospital) in Staunton, Virginia.

On the morning of 24 February 1883, just after receiving their regular liquid medications, seven male patients lost consciousness. Four died almost immediately, two died in the next three days, and one recovered. An eighth patient vomited and experienced other ill effects, but recovered in a few days. A coroner’s inquest concluded that the victims’ cups of medicine must have been poisoned while sitting in an unlocked hall cabinet the previous evening. Other patients, taking the same medicine which had not been left in the cabinet, had no problems. Dr. W.W.S. Butler, head pharmacist at the asylum, testified that no poisons were missing from the dispensary. Autopsies were performed, and University of Virginia chemistry professor John W. Mallet used the latest forensic techniques to analyze three of the victims’ stomachs and their contents. Mallet concluded that the poison used was aconitia (also known as aconitine), an extremely toxic extract of the aconite or monkshood plant, and the coroner’s jury agreed. The asylum pharmacy had a bottle of highly diluted “tincture of aconite,” but Mallet thought it was not strong enough to cause sudden death, and local drug stores did not stock any drugs derived from aconite.1

The superintendent of the asylum, Dr. Robert S. Hamilton, suspected the poisonings were politically motivated, intended to discredit him and the Readjuster-Republican coalition administration of Governor William E. Cameron. Cameron had made heavy use of his patronage power, including the appointment of a new asylum board of directors who in turn had appointed Hamilton and replaced most of the former staff. To investigate the case, Hamilton, with Cameron’s approval, hired the famed Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency. Two Pinkerton agents interviewed druggists in Richmond, Alexandria, Washington, Baltimore, and Philadelphia to see which ones had sold aconitia, but found no good leads.2

F. M. Smiley, a 27-year-old Pinkerton investigator with two medical degrees, went undercover in the asylum for over two months, posing as a patient suffering from “melancholia” (depression). 3 Soon the case had as many suspects as an Agatha Christie novel. Hamilton’s initial suspects were two melancholia patients: Charles J. Armistead, a former theology student who had once attempted suicide by drug overdose,4 and Bolivar Christian, a lawyer and former Confederate officer.5

Both were, in Hamilton’s words, “sharp, shrewd, highly educated and were also strong adherents of the opposition [Democratic] party and were bitterly opposed to the present management of the Institution.” Armistead was, according to Hamilton, “a thorough chemist” familiar with drugs. Christian had previously accused Dr. Butler of tampering with his own medicine. Both had access to the hall at the time when the medicine was poisoned.6 Detective Smiley, playing his part well as a patient who had occasional “bad spells” but was generally rational, gained the confidence of Armistead, Christian, and a third suspect, a supervisor named Hull who disliked Hamilton and, in the investigator’s opinion, “would stoop to any low cussedness.”7 Smiley also heard rumors that Dr. H. S. Crockett, Hamilton’s second-in-command, was “working his hardest to ruin Dr. Hamilton.”

Some people found it suspicious that Crockett’s uncle William B. Byars, who had been under treatment for melancholia at the asylum for three and a half years and who had unusual access to the pharmacy because of his family connection, was discharged three weeks after the poisonings and soon moved to Texas. “The general opinion is that Dr. C. furnished the ‘aconitia’ and that his uncle used it” to kill the victims, wrote Smiley.8 Asylum attendant Duet Andrews, one of the few remaining Democrats on the staff, told the detective that he thought the poisoning “was done to beat the d[amne]d readjusters and I wouldn’t squeal if I knew” who did it.9 Smiley suspected Andrews may have conspired with another attendant and with a former attendant, a “dirty mean scamp” who had been fired but returned to Staunton the day before the poisonings.10 On the other hand, the Democratic editor of the Staunton Telegram newspaper believed the poisonings were not murders, but accidents caused by Dr. Butler’s carelessness.11

Pinkerton superintendent R. J. Linden’s final report dismissed the possibility that a patient or staff member could have caused the deaths, concluding only that “the poisoning resulted from no carelessness or lack of precaution on the part of the faculty, but was evidently… perpetrated by parties outside of the institution, whom it is unnecessary and would also be injudicious to name at this time.” 12 Tantalizingly, Dr. Hamilton said “I have reason to believe that the detective had other information than that reported, and that he had other information which led him to suspect a certain individual.” For whatever reason, no charges were brought.13

While the asylum board of directors considered themselves and Hamilton to be vindicated, their political enemies thought otherwise. John N. Opie, Democratic member of the House of Delegates for Augusta County and Staunton, demanded an investigation of “gross mismanagement” at the asylum. 14 A special committee of House and Senate members, reflecting the Assembly’s new Democratic majority and chaired by Opie, concluded that:

- Professor Mallet’s conclusions were faulty; the tincture of aconite in the asylum pharmacy was sufficiently toxic to have caused the deaths. (According to the majority report, “five drops … will produce death,” but according to the minority report which sided with Mallet, a full medicine cup of the tincture would not contain “the amount of poisons as found by the analysis.”)

- The undercover Pinkerton agent was “a cheat and a fraud, whose purpose was to extort money from the superintendent…. The said detective declined to give any information either to the attorney for the commonwealth or to your committee.” (The minority report said there was no evidence of fraud.)

- There was “not the slightest scintilla of evidence to show that the poisoning was done by parties outside of the asylum.”

- “Whether the killing of these poor unfortunates was done by parties in or outside the asylum…the responsibility justly rests upon the officials placed over them.” (The minority report said the management and employees, far from being negligent, had taken more precautions than under previous administrations.)

- “The old tried and efficient officers and attendants were summarily removed [by Hamilton and the board] for no other cause than they were Democrats.”15

Spurred by the committee report and by other complaints, the General Assembly’s 1883-1884 session passed acts removing the boards of all state hospitals as of 15 April 1884, and putting the choice of new boards in the hands of the Board of Public Works instead of the governor.16 Soon Hamilton and his entire management team were out the door, and the old administrators from before the 1881 election were back in charge. There was one new staff member: clerk C. J. Armistead, one of the former inmates and suspects!17 The opponents and supporters of the ousted administrators agreed on only one thing: “the whole affair is still shrouded in doubt and mystery.”18 Over 130 years later, the mystery endures.

-Bill Bynum, Reference Archivist

Footnotes

[2] “Patient Poisonings: Pinkerton Investigation Reports” (hereafter Pinkerton Reports), WSH Box 78, folder 29.

[3] Admissions Register 1880-1889, WSH Vol. 249, patient number 3394; Annual Report of the Board of Directors and Superintendent of the Western Lunatic Asylum for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1883 (hereafter Annual Report 1883, p. 11; Case Book 1882-1889, WSH Vol. 278, p. 711.

[4] Case Book 1858-1869, WSH Vol. 276, p. 252-253.

[5] Case Book 1882-1889, WSH Vol. 278, p. 641.

[6] Pinkerton Reports, 23 May 1883, p. 4, WSH Box 78, folder 29. This report gave Christian’s name as Christy, but later reports corrected it to Christian. Bolivar Christian was the only man with that surname in the asylum at the time; see Annual List 1882-1883, WSH Vol. 311.

[7] Pinkerton Reports, 23 May 1883, p. 12; WSH Box 78, folder 29; 25 May 1883, p. 2, folder 30.

[8] Pinkerton Reports, 12 June 1883, p. 7, WSH Box 78, folder 31.

[9] Pinkerton Reports, 31 July 1883, p. 6, WSH Box 79, folder 1. See also testimony of former asylum employee Nelson Andrews (Duet’s brother?) in “Patient Poisonings: Proceedings of the Committee of Investigation of the General Assembly,” WSH Box 79, folder 2.

[10] Letter, R. J. Linden to Hamilton, 20 July 1883, “Patient Poisonings: Pinkerton Investigation,” WSH Box 78, folder 28; see also Pinkerton Reports, 12 July 1883, p. 1-2, and 31 July 1883, p. 5-6, both in WSH Box 79, folder 1.

[11] Pinkerton Reports, 5 July 1883, p. 2, ibid.

[12] Annual Report 1883, p. 13.

[14] Records of the Board of Directors 1867-1884, (2 Feb. 1884 meeting), p. 307-308, WSH Vol. 8, barcode 1183851.

[15] Journal of the House of Delegates of the State of Virginia for the Session of 1883-4 (Richmond: Supt. of Public Printing, 1883), 289-290 (majority report); Minority Report, 2-4.

[17] Reports of the Board of Directors … of the Western Lunatic Asylum of Virginia for the Fiscal Year 1883-84 (Richmond: Supt. of Public Printing, 1884), p. [2]; compare lists of officers in Annual Report 1883, p. [2], and Biennial Reports of the Board of Directors … of the Western Lunatic Asylum … 1879-80, 1880-81 (Richmond, Supt. of Public Printing, 1881), p. [2].

[18] Journal of the House of Delegates … 1883-4, 289.

Real mysteries are the best. Many thanks for this intriguing post!

Great post!

I have been researching my fathers family and have discovered that the brother of my Great Grandfather , my Great Grand Uncle was one of the men who died due to the 1883 poisonings. I am very interested in trying to find out why he was admitted to the Western State Lunatic Asylym in the first place

Because the date of his death is over 75 years ago, will they release information to me and where should I begin

Any help is much appreciated ! Thanks

Ms. Mears,

That is a very interesting connection to Western State Hospital! The hospital’s records are housed at the Library of Virginia. I encourage you to read the finding aid to gain an understanding of the types of records available. http://search.vaheritage.org/vivaxtf/view?docId=lva/vi00937.xml Once you’ve identified the boxes or volumes that you would like to review, you can request the materials in the Archives Reading Room (Monday-Saturday, 9AM-4:30PM). Because of the date, there should be few privacy restrictions that would impact the materials you will need to view.

Best of luck for success in your research, and thanks for commenting. Please share any additional information that you find!