Today we bring you a story in recognition of Census Day, April 1. Learn more about the 2020 United States Census (and submit your response!), by visiting the official website.

“The false returns stand to this day in the statistical tables of the census, to convince all cavillers of the unfitness of the Negro for freedom...In order to gain capital for the extension of slave territory, the most important statistical document of the United States has been boldly, grossly, and perseveringly falsified, and stands falsified to this day.”

Harriet Beecher StoweA Key To Uncle Tom's Cabin: Presenting the Original Facts and Documents Upon which the Story is Founded, 1854

The debates preceding the 2020 census bring into focus the highly contentious nature of this population count that occurs every ten years. Because the census is at the nexus of political power, prestige, and money, it often becomes a lightning rod of controversy. Racial tensions frequently surface in these debates. One of the fiercest of these involved the 1840 census, a debate that amplified the national divide over slavery and ultimately led to the birth of the modern census organization. What made this census particularly fraught was the way it suggested that achieving freedom made African Americans more prone to insanity—an implication based on misleading statistics.

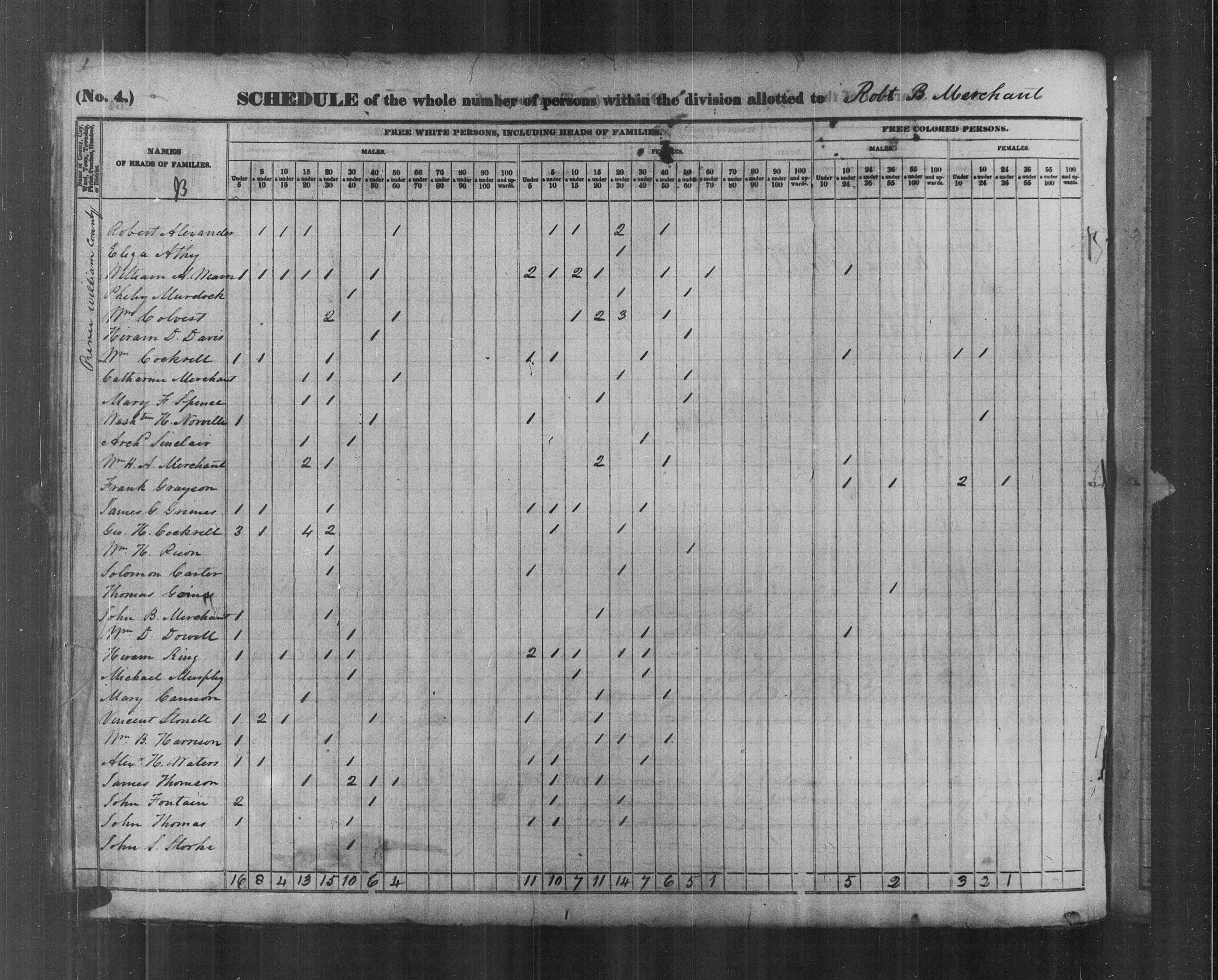

The sixth census was more ambitious than prior censuses. In answer to calls for additional statistical data about the population, the census added questions about education, military service, and disabilities. As with previous censuses, only the heads of household were named. Other household members were counted based on age and sex, with thirteen age divisions for whites, six age divisions for “free colored persons,” and a similar six for enslaved people. This census added an employment question broken into seven categories and established eight categories for education, including a category for illiteracy that applied only to white adult males. Like the previous census, it counted those who were “deaf and dumb” or blind, and added a new category for those deemed “insane and idiots,” divided into individuals kept “at public charge” and “at private charge.” Upon their unveiling, these census questions received scant criticism, with the superintendent of the census reporting that “from no man in either House of Congress came one word of censure.”

The uproar began about a year after the census statistics had been compiled and printed, when the prominent Richmond-based Southern Literary Messenger published a lengthy article entitled “Reflections on the Census of 1840” (Vol. 9, June 1843, pp. 340-352). It opened by noting the “dark shade” cast by the “startling amount of insanity among our people,” and bemoaned the high cost of caring for the afflicted. Turning to his main subject of slavery, the author noted that the number of free blacks in the North listed as insane was many times greater than the number of insane enslaved people listed in the South. According to the census findings, 1 in 143 blacks were insane in the free states, rising as high as 1 in 34 in New England. In contrast, the South had just 1 in 1,605. He predicted “general emancipation would be attended with most injurious consequences to the country… and eventually prove fatal to the emancipated race.” He went on to conclude that “slaves are not only far happier in a state of slavery than of freedom, but we believe the happiest class on this continent.”

Slavery supporters eagerly embraced these conclusions; finally, they had evidence to show that slavery benefited both the nation and the enslaved. These statistics soon found their way into congressional debates and even foreign policy. In deriding Great Britain’s support for the eventual suppression of slavery in the newly independent Republic of Texas, Secretary of State John C. Calhoun wrote to British minister Richard Pakenham on 18 April 1844 that “the census and other authentic documents show that, in all instances in which the States have changed the former relation between the two races, the condition of the African, instead of improved, has become worse. They have been sunk into vice and pauperism, accompanied by the bodily and mental inflictions incident thereto–deafness blindness insanity and idiocy to a degree without example.”

Abolitionists immediately questioned these perplexing numbers, and they soon found support from the leaders of the recently formed American Statistical Association. In his article “Insanity Among the Coloured Population of the Free States” (American Journal of the Medical Sciences, January 1844), Dr. Edward Jarvis noted that the returns for Worcester, Massachusetts, erroneously recorded all 133 white inmates of the mental hospital as black. He wondered if this had been the case elsewhere, and so he began a meticulous review of the numbers. He published some preliminary findings in November 1842 and a more complete report in January 1844, locating numerous instances of obvious mistakes. Indeed, many localities seemingly had more cases of insanity in blacks than there were black inhabitants. He speculated that census compilers in Washington had simply transposed the numbers to the wrong columns and urged that they immediately be reviewed and corrected.

In Congress, former president John Quincy Adams, then a 76-year-old member of the House of Representatives, spoke repeatedly on the House floor about the census errors, declaring that “atrocious misrepresentations had been made.” He claimed that the United States had been “placed in a condition very short of war with Great Britain as well as Mexico on the foundation of these errors.” He submitted several petitions protesting the errors, including one from the American Statistical Association that included Jarvis’s analysis. At first, Calhoun summarily dismissed these critiques, claiming that no “gross or material errors” had been discovered. After Congress grew more insistent, he enlisted the former superintending clerk of the census, William A. Weaver, to “give the subject a thorough and impartial investigation.”

When former Secretary of State John Forsyth had employed Weaver to oversee the census in 1839, it was the first time any census had a designated administrative officer. Although he lacked statistical training, Weaver, a former naval officer, had demonstrated a knack for efficient administration in a variety of temporary positions within the Secretary of State’s office over the previous seven years, including organizing the department’s diplomatic archives. Although Weaver’s original three-year census contract had expired in 1842, Calhoun brought him back in July 1844 for three months to oversee the review. Undoubtedly, Calhoun’s purpose in employing Weaver was not for “impartial” examination, but to defend the original findings, perhaps counting on Weaver as a fellow southerner and slaveholder. Weaver was born near Dumfries, Virginia, and had recently returned. The 1840 census showed that his household included eight enslaved people and one “free colored person.”

Weaver completed his census report in January 1845, and Calhoun presented it to Congress the following month. Adopting a tone of indignation, Weaver reprimanded the committee of the American Statistical Association for having “hastily” arrived at their conclusions. “A more critical investigation would have satisfied them that many of the specifications were frivolous—some totally unfounded; and the few errors… not at all calculated to impair the utility or destroy the general correctness of the census.” While he acknowledged some errors, he downplayed their significance overall. With regard to the 79 cases noted by the petitioners where black insanity in a locality had been reported as greater than the black population, Weaver found 11 where Jarvis had misread the numbers, and credited most of the remainder as likely “wanderers and vagrants, without local habitation.” He did grant that the Worcester case was a transposition of figures between columns. But he concluded by stating, “If there be errors… those errors are as likely to be on one side as on the other; and, on the principle of compensation of errors, it is not probably that they would materially influence the result.” Southern newspapers eagerly reprinted Weaver’s defense of the original findings. The Charleston Mercury proclaimed that it “utterly demolished” the census’s critics. “Mr. Weaver enters minutely into each specification of the Abolition Memorialists, and shows that in nearly every instance their ‘facts and figures’ are either fabrications or blunders.”

While Weaver’s report bolstered slavery supporters, many in Congress knew that it had not essentially answered critics’ concerns, and that the errors severely undermined confidence in the overall census statistics. Little could be done to correct the 1840 census figures. Congress did, however, take far greater care in planning for the upcoming 1850 census. Congress established a Census Board to oversee the process, and transferred responsibility from the Secretary of State to the newly formed Department of the Interior. Congress and the Census Board also sought advice from statistical experts, notably Edward Jarvis, Lemuel Shattuck, and Archibald Russell. Shattuck, in particular, became one of the major architects of the new census. This Boston bookseller, health reformer, and genealogist had designed and implemented a widely admired 1845 census of Boston. Congress adopted many of his recommendations, including collecting the names, ages, and birthplaces of everyone, not just the head of household. Shattuck even wanted to record the names of enslaved people, although southern legislators ultimately thwarted that effort. Not only did Shattuck contribute to the design of the census, but the Census Board also drew heavily on the guide that Shattuck had prepared for Boston census takers to develop their own comprehensive instructions.

The 1840 Census’s false association between freedom and insanity for African Americans would have lasting implications. It fed into a variety of pseudo-scientific theories that arose to support slavery and demean free African Americans. In 1851, one southern physician would propose that enslaved people who fled their captivity actually suffered from a mental illness that he called drapetomania. This disease, Samuel Cartwright explained, resulted when lenient masters led their enslaved people to believe that equality might exist between the races. While his conclusions received outright mockery from northerners and medical experts, they found influence and popularity in the South. Even after the Civil War ended the need to prop up slavery, the remnants of these theories relating freedom to insanity continued to circulate in both scientific and lay publications into the next century.

-Kevin Shupe, Senior Reference Archivist