While working with the Virginia War History Commission WWI Questionnaires collection, I have often wondered what it must have been like living through that time, when the United States was not only involved in an international war but also facing a severe flu pandemic. There were those who survived the war only to die of flu, or escaped the flu only to die later because of exposure to gas. My own grandfather was one such veteran, leaving behind a wife and two infant children.

Some of the documentation that has touched me the most is the letters home to loved ones. Reading these letters as a parent, I find them both heartbreaking and poetic. I know I would have held onto those letters and read them over and over in times of grief.

One soldier in particular who caught my attention was George Calvin Wilkinson of Petersburg. He was 22 years old when he was inducted into the service on 22 April 1918, according to the questionnaire about Wilkinson’s World War I service. He had been married for just six months and was working as a bricklayer for his father. Wilkinson spent time at Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana and Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, before departing from Hoboken, New Jersey, for France. He arrived on French soil on 3 September 1918.

The questionnaires were gathered by the Virginia War History Commission, whose goal was “to complete an accurate and complete history of Virginia’s military, economic, and political participation in the World War.” The commission conducted a survey of World War I veterans in Virginia, asking about their wartime experiences and how the war affected them.

George Wilkinson’s questionnaire was filled out by his father, John T. Wilkinson. The third page of the questionnaire asked about the veteran’s war record, including engagements he had participated in. The elder Wilkinson answered that his son had served in the Toul Sector “Till stricken ill with influenza. Pneumonia followed.” George Wilkinson died of pneumonia at Base Hospital 116 in Bazoilles-sur-Meuse on 8 October 1918. Five days later, across the ocean, his wife gave birth to a daughter.

The family included both photographs and letters in the questionnaire. It is in these letters that you receive a glimmer of light in an otherwise dreary situation. Writing on 13 October 1918 from the American Red Cross base hospital, Nurse Mary E. Gross told the Wilkinsons:

He [George] was very brave, and though seriously ill he was always thinking of others. Last Sunday morning he heard of a friend in his ward who was in need, so he immediately sent him some money. On Monday morning he was very weak, and on Tuesday at 12:55 P.M. the end came very peacefully and quietly. He was conscious almost to the last and his last thoughts were of you. I knew that he was wishing that you were by his side.

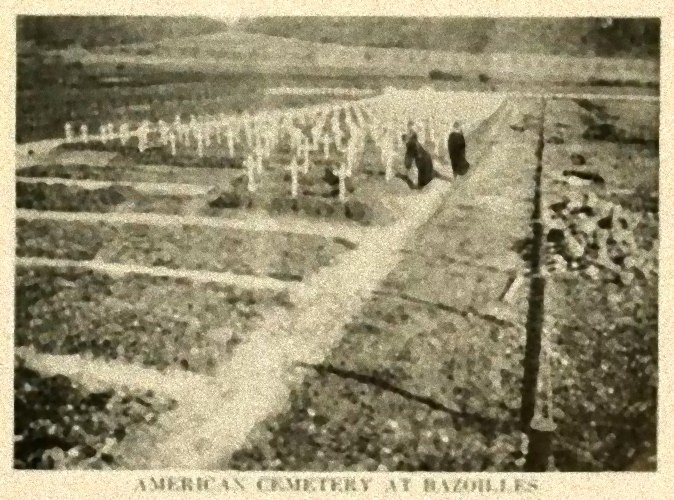

She continued, “I could not help wishing that you could see the quiet peaceful spot which marks his last resting place. At his head is a wooden cross with a name plate and the location has been registered with the Graves Registration Bureau so you may find it after the war. Believe, Mrs. Wilkinson, that in the loss of your son, you have my sincere sympathy; may you find comfort in the thought of a life where there is no parting.”

We do not have a photograph of George Wilkinson’s grave, which was recorded as grave No. 126 in the American Cemetery at Bazoilles-sur-Meuse in Vosges, outside the hospital where he died. It was one of many temporary graves for American soldiers in France, which were generally marked as Nurse Gross described, with a simple cross and a bottle filled with identification information. Like so many others, Wilkinson’s body awaited a time when his family could transfer his remains back to the United States.

The National Archives and Records Administration has a digitized collection of records related to these re-interments of World War I veterans, a massive undertaking in the years after the war. The process can be seen in this historical footage, though viewer discretion is advised. Some families chose not to have the bodies of their loved ones returned to the United States. These remains were consolidated in permanent American Cemeteries, and those mothers and widows (who had not remarried) who could not afford European travel were invited to visit the graves. Mary Derrickson was one such Virginia mother, who traveled to France in 1930 as part of the Gold Star pilgrimages to see the grave of her son Paul Derrickson.

The index card for George C. Wilkinson records that his remains were disinterred on 2 February 1921 and sent to his father in Petersburg. He was re-buried in Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg. His tombstone detailed that he “died in France,” every bit as much a victim of World War I as those who died on the battlefield.

The World War I questionnaires are filled with stories like this, of lives interrupted by the chaos around them. However, they can be hard for people to decipher as they are often written in longhand. We are endeavoring to transcribe these forms so that they will be more readable and searchable for the public. While you are sheltering at home perhaps you’d like to take a moment to help us on our From the Page site. While many of the stories are as tragic as this one, others have happier endings, interesting reminiscences, and wonderful attachments such as pictures.

–Rose Schoof, Library of Virginia Volunteer and former Technology Consultant