In August 1852, Elizabeth McKennon was accused of assembling with “fifteen negroes” at a house on Second Street in the City of Richmond with the purpose of instructing them to read and write. The trial papers refer to Elizabeth McKennon as a “white person” but McKennon’s race was not an obvious or a well-determined fact. Two months following her accusation, McKennon submitted to the court that she was “not a negro.” On the testimony of three white men, on 21 October 1852, the court certified that Elizabeth McKennon, “a woman of mixed blood,” was in fact “not a negro.”

Documents from the trial held the following year reference this court proceeding as a certificate. An 1833 Act of the General Assembly allowed people of mixed blood to obtain a certificate proving they were “not a negro” protecting them from laws to which free Black people at the time were subject. These individuals needed a white person to testify on their behalf.

1833. Chapter 80. County courts are authorized to grant a certificate to any free white person of mixed blood not being a white person, nor a free Negro, that he or she is not a free Negro, which certificate shall be sufficient to protect such person against the disabilities imposed by law on free Negroes.1

In last month’s blog post about William Pemberton, we shared about biracial and multiracial lineages in Virginia. One was considered “mixed race” if one contained more than ¼ “negro” blood in their veins. The white men who testified–William Barret, William W. Dunnavant, and Clement White–probably stated that they knew McKennon’s parents and grandparents, thereby confirming that a majority of them were white individuals. The minute book entry notes that this case was “copied and paid.”2 McKennon, or her attorney, was likely required to pay for this certificate proving her race.

McKennon was brought to court for the first time in November 1852, but the trial was moved to the next term of court. Four months later, on 19 April 1853, the jury returned a verdict of guilty and charged McKennon a $6.50 fine. On that day, Richmond papers reported that “Elizabeth McKennon, a woman of mixed blood, was put upon trial as a white woman.”

The following day, McKennon and her attorney filed a bill of exception acting as an appeal to the court’s ruling. The bill of exception stated that yes, McKennon’s earlier certificate instructed the court that McKennon was “not a negro.” But McKennon was tried as a white person. This was both incorrect and against the law. McKennon may not have been Black but she was also not white. She objected to being tried as a white person. Why was this so important to her? Well, McKennon was no doubt charged on the Act of the General Assembly of 1848, which stated that:

Any white person assembling with slaves or free Negroes for the purpose of instructing them to read or write, or associating with them in any unlawful assembly; shall be confined in jail not exceeding six months and fined not exceeding $100.00.3

If McKennon could claim status as a person of mixed blood, she could not be charged with this offense. It’s unclear what action the court took in response to this appeal. The bill of exception was not recorded in the minute book; it only lives as a loose document filed in her court papers. Regardless, it was a valuable instrument allowing McKennon to voice her response, albeit through her attorney.

In May 1853, McKennon “surrendered herself into custody” and was sentenced to jail for one hour until her fine and court costs were paid. McKennon paid her costs and presumably was set free. The highest possible punishment for this offense was set at a fine of $100 and six months imprisonment. McKennon fared far better than that. Did the bill of exception work?

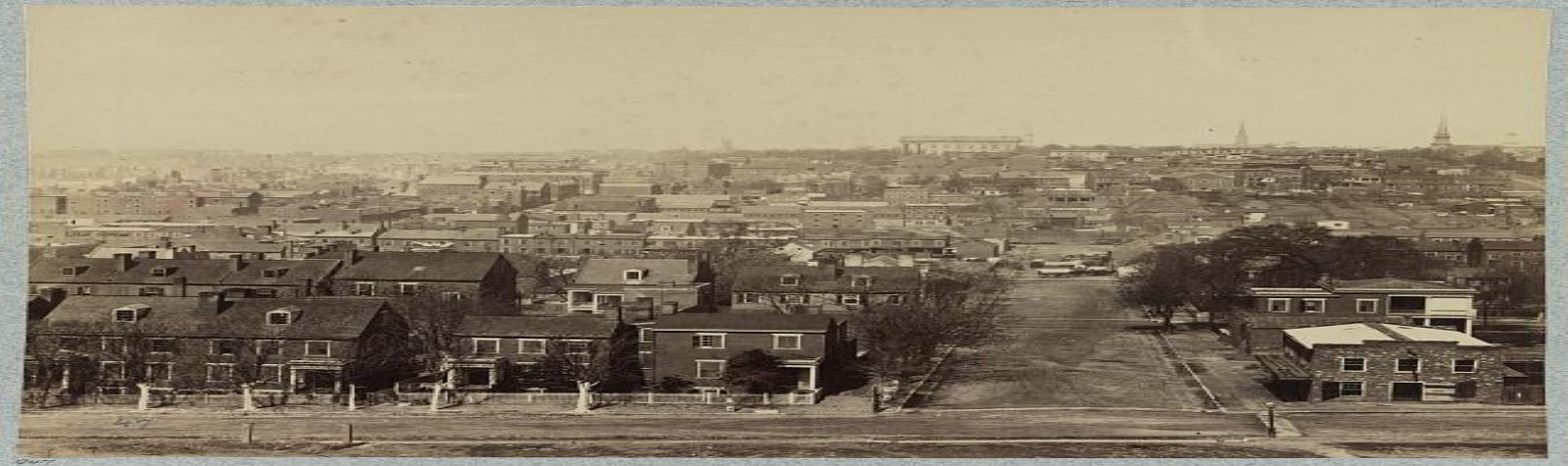

An Elizabeth “McKinnon” appears in the 1850 and 1860 censuses, living in the City of Richmond with individuals who were probably relatives. In the 1860 census, McKennon is the only individual listed with an occupation: nurse. In both census records, McKennon is listed as white. In the 1850s, however, she is surrounded by neighbors who are both “Black” and “Mulatto.”

Could these neighbors be her pupils? The newspaper’s phrasing, “teaching a school of negro children,” paints a picture of an organized, continuous gathering, and at the helm: Elizabeth McKennon. No doubt that fifteen Black people assembled together for the purposes of expanding their minds made white officials nervous. The court documents literally state that McKennon had committed her offense “against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth of Virginia.” Another shortened document reads that McKennon had acted “against our peace and dignity.” How does teaching people basic education disturb the peace? Disrupt dignity? Education is empowerment. Many would argue it is also a basic right. While this blog post has centered on the story of Elizabeth McKennon, consider for a moment the unnamed individuals she was teaching. McKennon went to jail for a few hours. These individuals lost a chance at education.

I have to wonder if Elizabeth McKennon continued her school. Perhaps after being freed from jail, she moved her instruction to a more secret location or guised her teaching with another form of interaction. If she was determined enough to prove her racial identity to a panel of white justices, I like to think that she was determined enough to continue empowering others through basic education—even in the face of legal consequence.

Elizabeth McKennon’s court case is part of the Richmond (City) Ended Causes, 1840-1860. These records are currently closed for processing, scanning, indexing, and transcription, a project made possible through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program. An announcement will be made when these records are added to the publicly-accessible digital Virginia Untold project.

Footnotes

- Jane Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia, (Fauquier County: Afro-American Historical Association of Fauquier County, 1995), 108-108.

- Minute Book, 1852-1853, City of Richmond Circuit Court Records, Barcode #1109105. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

- Guild, 178-179.

Sources

Commonwealth v. Elizabeth McKennon, 1853, City of Richmond Circuit Court Records. Local Government Records Collection. (closed). The Library of Virginia.

Minute Book, 1858-1859, City of Richmond Circuit Court Records, Barcode #1109097. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

Morning Mail, 20 April 1853.

Guild, Jane Purcell. Black Laws of Virginia. Fauquier County: Afro-American Historical Association of Fauquier County, 1995.

Ancestry.com. 1850 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.