Between the spring of 1915 and the fall of 1916, between 664,000 and 1.2 million Armenians within the Ottoman Empire died.1 The Armenian Genocide and the Armenian resistance to the Ottoman Empire that continued through World War I prompted a massive relief effort within the Christian community in the United States, as well as a push among Armenians to create their own country. Evidence of these movements may be found in several disparate collections that are held by the Library of Virginia.

By the 1880s, Armenian Christians within the Ottoman Empire were fighting hard for autonomy, ultimately capturing Constantinople’s National Bank building along with 100 hostages on October 17, 1895. The Ottomans increased their persecution of the Armenians after this incident, and 80,000 Armenians died between 1894 and 1896. A 1909 clash in Adana resulted in the deaths of 20,000 Armenians and 2,000 Muslims. The Armenian Genocide began on April 24, 1915 with the deportation of 240 leaders from Constantinople who were accused of siding with the Allies, rather than with the Ottoman-backed Central Powers during World War I. Deportations to Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq continued, particularly among the Christian Armenians who did not convert to Islam. Most men were murdered, and the surviving women and children endured considerable violence and shortages that often resulted in their deaths.2

Despite such extreme losses, Armenians continued to work towards independence. On April 22, 1918, Armenia joined with Azerbaijan and Georgia to create the Transcaucasian federation after Russia fell to the Soviets. Turkish influence resulted in the end of this arrangement five weeks later and the creation of an independent Armenia, although the country lost some territory to the Turks. Two years later in September 1920, Turkey invaded Armenia. They were quickly followed by the Soviets, who created the Soviet Republic of Armenia on November 29, 1920. Armenia began the process of joining the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in December 1922 and became a full member in December 1936.3 This put a stop to Turkish violence against the Armenians.

Christians around the world took a particular interest in the Armenians’ situation. They were viewed as long-suffering Christians in a predominantly Muslim Ottoman Empire and revered as the first to designate Christianity as their national religion in ca. 300. There was also a considerable missionary presence in Palestine, the Persian Empire, Anatolia, and Syria—primarily those employed by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (now the United Church Board for World Ministries)—who could see first-hand what was happening to the Armenians. Their work was absolutely impacted in that the ministers they trained were among those who were deported.4

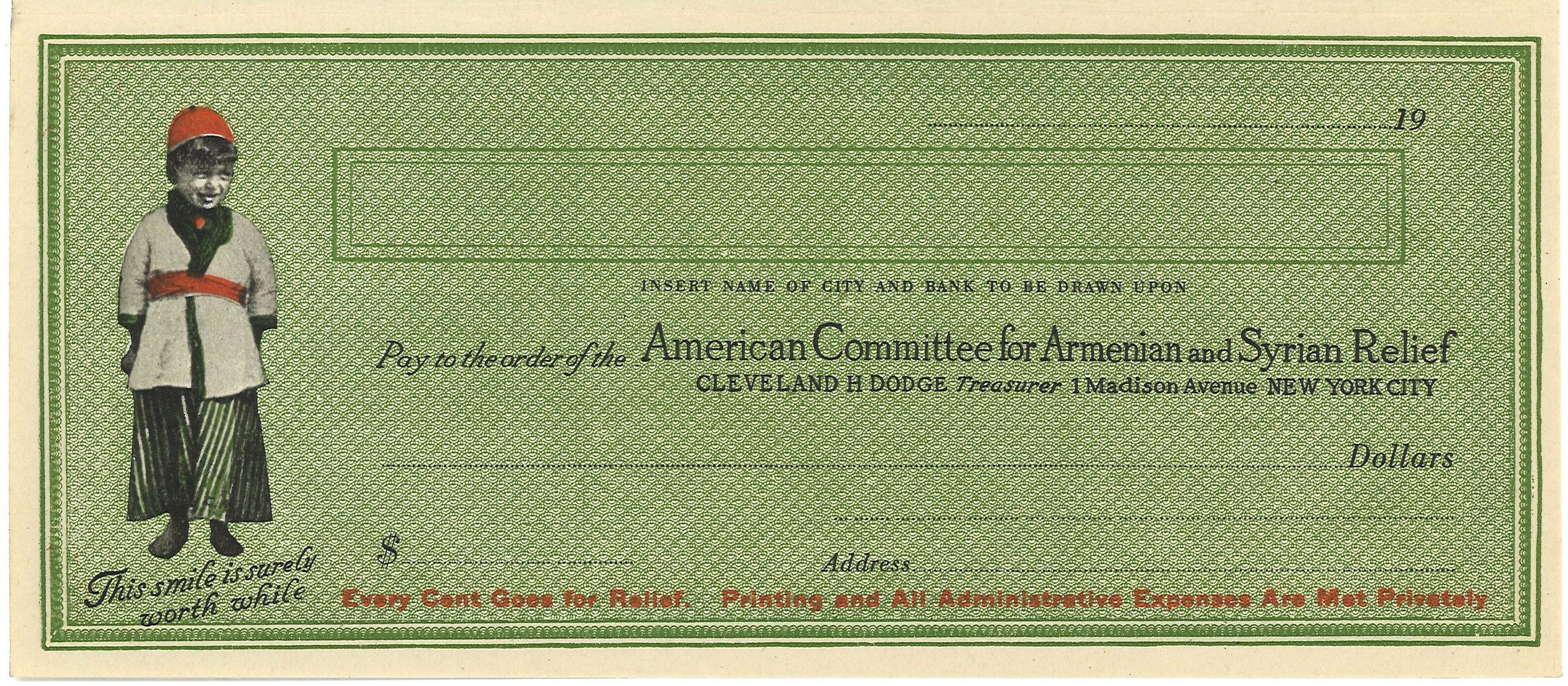

Consequently, relief efforts often had a Christian focus. On September 3, 1915, Ambassador to Turkey Henry Morgenthau, Sr. wrote to Secretary of State Robert Lansing: “Will you suggest to Cleveland Dodge, Charles Crane, John R. Mott, Stephen Wise, and others to form committee to raise funds and provide means to save some of the Armenians and assist the poorer ones to emigrate. . . ?” That communication resulted in a merger of the Armenian Relief Committee, the Persian War Relief Fund, and the Syria-Palestine Committee that same year to form the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief. It was chaired by James L. Barton, who was the foreign secretary for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, and Cleveland Dodge served as treasurer. It underwent several name changes—American Committee for Relief in the Near East in 1918, Near East Relief in 1919, and Near East Foundation in 1930, a name that it retains today. Barton collected information on events in Turkey and spread information as far as he could through the media contacts, distributing pamphlets, lobbying the federal government, and even being the driving force for a Presidential Proclamation declaring October 21 and 22, 1916, “as joint days upon which the people of the United States may make such contributions as they feel disposed for the aid of the stricken Syrian and Armenian peoples.” The organization raised $11 million by 1918 and became the second largest relief organization, following the American Red Cross.5

Evidence of relief efforts by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief (ACASR) are found in several collections in the Library of Virginia’s holdings.

The Gravely Family Papers, 1753-1988 (Accession 34126) document the Gravely family of Henry County, and includes business records, correspondence, and genealogical research. The files of furniture manufacturer Richard Pleasants Gravely, Jr. (1914-1988) include most of the materials that the ACASR suggests for a donation drive, including instructions for the best place to hang a poster, donation envelopes, a donation form designed to look like a check, suggestions for church services that focus on the donation campaign, and a pamphlet with stories about children who were involved with the genocide. Also included are an order form for materials, suggestions for organizing donation campaigns, and a stamp booklet that allow children to tear off a stamp for each item (such as candy or a trolly ride) that they give up so that the money saved could be donated to ACASR. Similar materials are included in the collection’s subject files.6

Stamp Booklet, American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief.

Gravely Family Papers, 1753-1988, Accession 34126, Personal Files, Richard P. Gravely, Jr., Box 28, Folder 1: Armenians, Starving, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

A February 1919 ACASR newsletter is included in the records of the Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO), 1849-ca. 1995 (Accession 37345). VEPCO (now Dominion Virginia Power) was founded in 1909, which makes it a contemporary of ACASR. Given that this is not a likely place to find an ACASR newsletter, perhaps it is a testimony of just how far ACASR reached. The newsletter focuses on the progress of the relief campaign, as well as updates from those who could see the situation of the refugees first-hand.7

An example of the ACASR efforts to reach government officials is included in the executive papers of Governor Westmoreland Davis (Accession 21567a). On November 5, 1919, Oliver J. Sands, State Chairman of the Virginia Division of ACASR, invited Governor Davis to “a Meeting of the workers for The Relief in the Near East, to be held in the Chamber of Commerce Auditorium, November, 10th.” He noted that two of the speakers “have just returned from Constantinople, and will bring fresh messages from the stricken country.” The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported on this meeting in the November 11, 1919 edition, noting that “While the world is celebrating Armistice Day in commemoration of the signing of the truce which resulted in the cessation of the most destructive war in history, Armenia, in the Near East, is still struggling for existence against the Turk and conditions which have been but slightly ameliorated since a year ago.” The attendees sent telegrams to President Woodrow Wilson, Senator Claude A. Swanson, and Representative A. J. Montague asking them to support relief for Armenians, Syrians, and Assyrians. Attendees also decided to hold a Christmas campaign drive and appealed specifically to mothers. There is no indication that Governor Davis attended the event.8

The T. Turner Foster Papers, 1740-1978 (Accession 45111) include accounting records for Armenian relief. Foster worked at Fauquier National Bank in Warrenton and owned a farm in The Plains, both of which are in Fauquier County. Donations appear to range from $1.00 to nearly $100.00. The records cover 1918 to 1925 and include an account book and documents from The Farmers Bank in The Plains.9 The name of the receiving organization is simply “Armenian Relief Fund.” It could be the ACASR or another organization with a similar mission. Despite this ambiguity, the records provide insight into the amount of money that individuals might give for Armenian relief.

Armenian organizations that were more political in nature are represented in the executive papers of Governor Westmoreland Davis.

On October 28, 1919, Governor Davis wrote to the president of the Armenian National Union of America (ANUA), Miran Sevasly, to express support for the organization’s relief efforts and confidence that Virginians and Congress would consider assisting with the relief effort. The ANUA was created in 1917 by the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Armenian Evangelic Church, the Armenian Social Democratic Hunchakist Party, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, the Reformed Armenian Hunchakist Party, the Armenian Constitutional Democratic Party, and the Armenian Benevolent Union. The organization’s goals were “1. Relief work for those destitute in Armenia and for the restoration of ruined and devasted provinces, 2. Armenian propaganda and diplomatic representations to the allied powers with the ultimate aim in view, namely: 3. Armenian self-government.” They were allied with the ACASR in that they forwarded donations to them. The ANUA’s activities through April 1919 were chronicled in The Armenian Herald.10

Governor Davis’s executive papers also include a May 19 [1919] telegram from James W. Gerard of the American Committee for the Independence of Armenia (ACIA) requesting that the governor contact President Woodrow Wilson in support of the de facto Armenian government, which wished to participate in the Paris Peace Conference at the end of World War I. The ACIA was created in 1919 by Vahan Cardashian, who resigned from his work with the Ottoman Embassy at the time of the Armenian Genocide. James W. Gerard was the organization’s chairman. There is no indication in the executive papers that Governor Davis wrote to President Wilson, but Armenia received de facto recognition in April 1920. The organization continues today as the Armenian National Committee of America.11

Although records concerning Armenians are few in number within the LVA Catalog and the Library of Virginia’s finding aids in Archival Resources of the Virginias, looking into the histories of the organizations represented provide considerable context for the histories of the 485,970 individuals of Armenian descent in the United States today, 5,834 of whom live in Virginia.12

Footnotes

[1] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, “The Armenian Genocide (1915-16): In Depth,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, Website of the United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum, accessed 26 April 2023, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-armenian-genocide-1915-16-in-depth.

[2] Imogen Bell, ed., Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2003, 3rd ed. Regional Surveys of the World (London and New York: Europa Publications, 2003), 74; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, “The Armenian Genocide (1915-16): In Depth,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, Website of the United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum, accessed 26 April 2023, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-armenian-genocide-1915-16-in-depth; “Armenian and Syrian Relief Fund,” Website of the National WWI Museum and Memorial,” accessed 26 April 2023, https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/spotlight-armenian-and-syrian-relief-fund

[3] Imogen Bell, ed., Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2003, 3rd ed. Regional Surveys of the World (London and New York: Europa Publications, 2003), 74.

[4] “Armenian and Syrian Relief Fund,” Website of the National WWI Museum and Memorial, accessed 26 April 2023, https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/spotlight-armenian-and-syrian-relief-fund; Gardiner H. Shattuck, Jr. “Weeping over Jerusalem: Anglicans and Refugee Relief in the Middle East, 1895-1950,” Anglican and Episcopal History 80:2 (June 2011): 188-121; Joseph L. Grabill, “Cleveland H. Dodge, Woodrow Wilson, and the Near East,” Journal of Presbyterian History 48:2 (Winter 1970): 254.

[5] Mark Malkasian, “The Disintegration of the Armenian Cause in the United States, 1918-1927,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 16:3 (August 1984): 350; “History,” Website of the Near East Foundation, accessed 26 April 2023, https://www.neareast.org/who-we-are/; Grabill 254-257, 260-261; “Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Robert Lansing (1864–1928),” Website of the Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, accessed 26 April 2023, https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/people/lansing-robert; Broadside, Gravely Family Papers, 1753-1988, Accession 34126, Personal Files, Richard P. Gravely, Jr., Box 28, Folder 1: Armenians, Starving, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA; Gravely Family Papers, 1753-1988, Accession 34126, Subject Files, Box 40, Folder 23: Armenian and Syrian Child Relief, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA; U. S. President, Wilson, The proclamation of the President of the United States of America to the American people and The message of the Federal council to the churches and Christians of America (New York, n.p., 1916), https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.13201600/.

[6] “A Guide to the Gravely Family Papers, 1753-1988, A Collection in the Library of Virginia, Accession Number 34126,” accessed 26 April 2023, https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=lva/vi00103.xml; Gravely Family Papers, 1753-1988, Accession 34126, Personal Files, Richard P. Gravely, Jr., Box 28, Folder 1: Armenians, Starving, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA; Gravely Family Papers, 1753-1988, Accession 34126, Subject Files, Box 40, Folder 23: Armenian and Syrian Child Relief, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA; Ancestry.com, Virginia, U.S., Death Records, 1912-2014 [database on-line] (Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015), Entry for Richard Pleasants Gravely, 4 October 1988, Roanoke, VA.

[7] American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, News Bulletin, 3:9 (February 1919), Virginia Electric and Power Company Records, 1849-ca. 1995, Accession 37345, Box 49, Folder 19: American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief news bulletin, February 1919, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[8] Oliver J. Sands, State Chairman, American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, Virginia Division, Suite 320, American National Bank Building, Richmond, VA, to Governor Westmoreland Davis, The Mansion, Richmond, VA, 5 November 1919, Executive Papers of Governor Westmoreland Davis, 1911-1922, Accession 21567a, Box 4, Folder 5: Armenia, 1919, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA; “Armenia Suffers while World Observes Peace,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 11 November 1919, 12.

[9] T. Turner Foster Papers, 1740-1978, Accession 45111, Box 30, Folder 7: Armenian Relief Fund, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[10] Governor Westmoreland Davis to Miran Sevasly, President, Armenian National Union of America, Southern Building, Washington, DC, 28 October 1919, Executive Papers of Governor Westmoreland Davis, 1911-1922, Accession 21567a, Box 4, Folder 5: Armenia, 1919, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA; “The Deportation of the Armenians and the World War,” The Armenian Herald, December 1917, 55-56, Online: https://books.google.com/books?id=LRo9AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false and https://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/6600768.html.

[11] James W. Gerard, One Madison Avenue, New York[, NY], to Westmoreland Davis, Richmond, VA, 29 May [1919], Executive Papers of Governor Westmoreland Davis, 1911-1922, Accession 21567a, Box 4, Folder 5: Armenia, 1919, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA; Mark Malkasian, “The Disintegration of the Armenian Cause in the United States, 1918-1927,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 16:3 (August 1984): 351-352, 354; “From Being Inspired to Inspiring Others: Vahan Cardashian Awardee Ken Sarajian,” Website of the Armenian National Committee of America, accessed 26 April 2023, https://anca.org/from-being-inspired-to-inspiring-others-vahan-cardashian-awardee-ken-sarajian/.

[12] U.S. Census Bureau, American FactFinder: People Reporting Ancestry, Universe: Total Population, 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates (B04006), https://ia801007.us.archive.org/34/items/2017ancestrybystate/2017%20ancestry%20by%20state.pdf

Header Image Citation

Blank Check, American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief.

Gravely Family Papers, 1753-1988, Accession 34126, Personal Files, Richard P. Gravely, Jr., Box 28, Folder 1: Armenians, Starving, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.