Richmond Times Dispatch, September 01, 1935, page 35.

In September 1935, the Richmond Times-Dispatch grabbed readers’ attention with the dramatic headline, “Buckroe Fish Packer Now Devil’s Nemesis.” The feature provided an early glimpse into the amazing life of pioneer Elder Lightfoot Solomon Michaux, dubbed at the time the “world’s greatest radio evangelist” by the New York Amsterdam News and the “best known colored man in the United States today” by the Washington Post. Online databases, especially Virginia Chronicle, the Library of Virginia’s digital newspaper archive, help us to document his extraordinary life.

Born in Newport News in 1884, Lightfoot Solomon Michaux (pronounced mi-SHAW) grew up in his father’s grocery business and quit school after the fourth grade to become a seafood peddler. He sold fish at the Norfolk Naval Base and at Camp Lee before moving in 1917 to Hopewell, a raucous boomtown because of DuPont’s munitions production during World War I. He judged it “a regular Gomorrah” full of vice, gambling, and crime, but without religion. Heeding a call to the ministry, he was ordained in the Church of Christ (Holiness) U.S.A. and held services on land donated by DuPont.

After establishing a Church of Christ congregation back in Newport News after the war, “Elder” Michaux soon founded the independent Church of God. Describing his ministry as non-denominational, “because I think when a man does right he is right regardless of the church to which he belongs,” he emphasized to his parishioners that God’s will extended into their everyday lives and that they should work industriously to serve God and adhere to his biblical word.

Michaux was arrested in 1922 for leading a group in singing on a Newport News street at 4 a.m. as they tried to recruit new congregants. A story in the Strasburg News recounts Michaux grandly arriving at the court with scores of congregants trailing him. The judge continued the case and admonished Michaux not to gather again. Michaux, however, said it wasn’t up to him but rather “It rests with God.” They returned to their morning singing and he was arrested once more, but this time found guilty and fined. Running afoul of the law again, in September 1926 Michaux was arrested for breaking segregation laws by baptizing Blacks and whites at the same revival event. The charges were dismissed because the white attendees had left town.

To broaden his message, in 1919 Michaux began airing a local radio broadcast. Finding success, he relocated to Washington, D.C. in 1928 to expand his radio ministry. Within a few years the program was syndicated nationally on the CBS radio network, with hour-long shows on Sunday mornings and evenings. With his wife Mary alongside as a featured exhorter and singer, the broadcast featured sermons of hope and inspired audiences during the Great Depression.

The show’s theme song, “Happy Am I,” caught on to such a degree that Michaux became known as the “Happy Am I preacher.” Emphasizing this theme, he commented that “Singing with its rhythm takes the congregation and the radio audience away from their cares. It makes them happy. Happiness is part of religion. A person shouldn’t come to church with a sad face. He should come with a glad heart.”

As his popularity soared, Michaux established branch congregations along the eastern seaboard in Newport News, Hampton, New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, boasting thousands of parishioners. He returned to Newport News often, such as in April 1935 to lead a massive fish fry that the Suffolk News-Herald reported attracted 400 of his “followers” and scores of white observers.

By the mid-1930s, the radio program was being transmitted to Europe, South Africa, and elsewhere internationally via short-wave radio, and the BBC aired two broadcasts in 1936 and 1938. A decade later his program appeared on a local D.C. television station, one of the first African American shows to appear on the new medium. Michaux emphasized that “Our parish is the world. My war on the Devil is an endless revival and its aim is: a million family altars in the homes of American citizens who will gather together at our regular broadcast to hear the Holy Word, to pray together and to sing as one united people.”

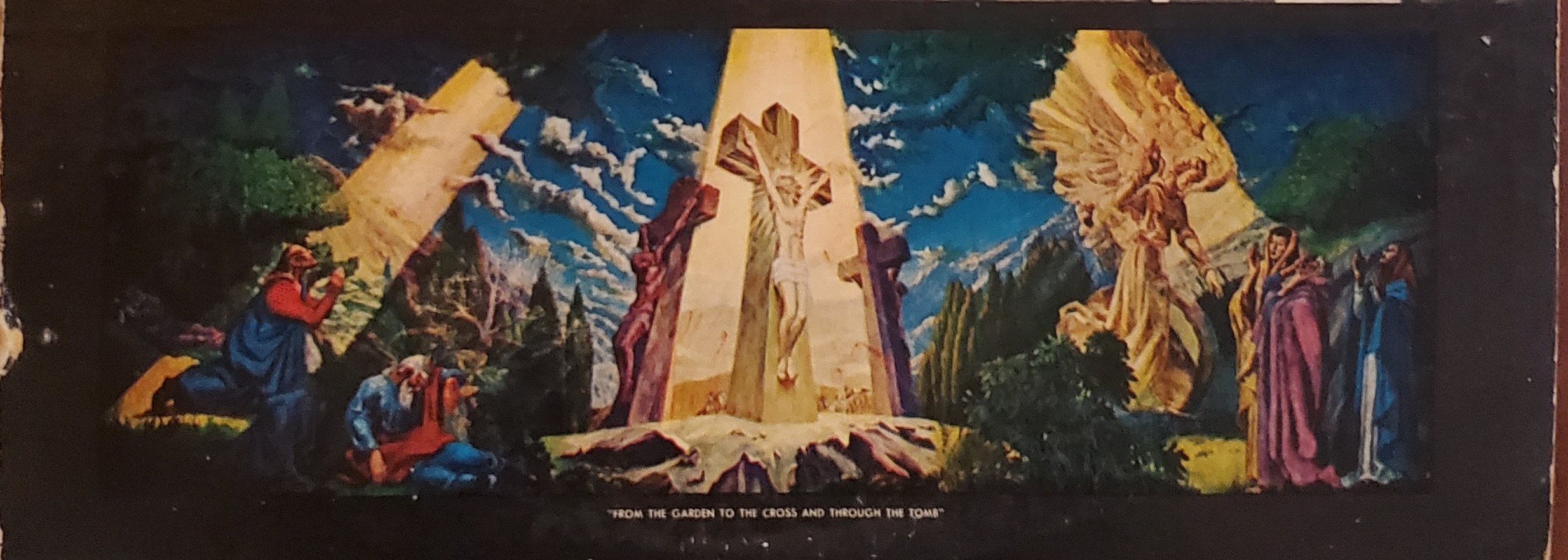

For more than two decades beginning in the 1930s, Michaux held large annual revivals at Washington, D.C.’s Griffith Stadium, drawing tens of thousands of spectators—both Black and white—on each occasion. Groups came by bus and train along the eastern seaboard and from as far away as Chicago. More pageants than services, these spectacles featured a large marching band, 150-member choir, a dramatic depiction of Satan’s burial, and an inspiring portrayal of the second coming of Jesus Christ. These revivals culminated in mass baptisms of hundreds in a giant tank in the center of the stadium, in later years with water Michaux famously shipped from the River Jordan. Reflecting on these baptisms, he proclaimed that “The only spirit I know that will make a white man from Mississippi come to Washington to be baptized by a colored man is the spirit of Jesus Christ.”

Taking his revivals to New York City in 1934, the Gloucester Gazette reported Michaux exhorting, “I’m going to drive the devil out of Harlem.” The following year he held revival services at a couple of Richmond venues. Admission was free, but reserved seating was held for those who had purchased one of his books. Over the years his local appearances expanded in scope. A Northern Neck News advertisement announced a June 1952 show, complete with his “World Famous Choir,” along with speeches by local officials and even a parade. Most significantly, the ad noted that “All Are Welcome” at the service “Regardless of Race, Creed, or Color.”

As part of serving God, Michaux believed in a “practical Christianity” that helped the needy by such deeds as donating proceeds from the church grocery and delivering meals from the Happy News Café (reportedly 250,000 meals in 1934 alone). He built affordable apartments for African Americans displaced by federal office expansion early in the 1940s, reported at the time to be the largest Black-owned and operated project in the U.S., and constructed another apartment complex in D.C. two decades later.

In this spirit, Michaux acquired in 1936 more than 1,000 acres of land near Jamestown to establish a National Memorial to the Progress of the Colored Race in America, which would include an auditorium, park, broadcasting station, and “the preservation of works depicting the progress of the negro race.” Additionally, one hundred families would live in a cooperative settlement and a school established to learn farming techniques. In Hampton Institute’s Southern Workman, Michaux explained that to achieve economic success, African Americans “must find a way to develop themselves from the soil which is the backbone of every industry.”

While the national memorial failed to materialize, Michaux continually worked to observe the arrival of the first enslaved persons to Virginia. As described in the Radford News Journal, he received permission in 1957 to hold a program at the Jamestown Festival commemorating the 350th anniversary of the colony’s founding.

An earlier supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Michaux has been credited with helping steer Black voters to the Democratic Party. By the mid-1940s, Michaux’s notoriety had spread to the extent that he was a go-to minister for religious quotes. A November 1945 Warren Sentinel editorial about the post-World War II use of the atom bomb parroted this nugget: “Elder Michaux tells his parishioners to love their enemies, ‘but watch ’em.’ Not a bad philosophy for our government to follow at this time of potential peril.”

Under a headline of “Stalin To Get Religion,” the Arlington Daily Sun reported in November 1952 that Michaux worked to print Russian-language Bibles, even aspiring to send one to Joseph Stalin. The Suffolk News-Herald relayed that Michaux presented President Harry Truman with a Russian-language Bible to represent a shipment that the American Bible Association was looking to smuggle into the Soviet Union.

Michaux later gravitated toward the Republican Party, supporting Dwight D. Eisenhower, who became an honorary deacon at the pastor’s church, for president. In December 1964, Michaux urged Martin Luther King Jr. to apologize to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover for comments King had made about the bureau’s failure to investigate civil rights cases. The following year, Michaux led a group of more than 100 in protesting King at a Southern Christian Leadership conference in Baltimore.

Michaux died of a heart attack on October 20, 1968. Recognized for his radio evangelical work, his large revivals, and influence in the African American community nationwide, he garnered obituaries across the country. More than 3,000 attended his memorial service in the Newport News Church of God where he had started four decades before. Owing to his deep faith, a sign was placed in his casket that read: “My Bible and me to the end.”