Conceived of by financier Morton Blumenthal, inspired by twentieth-century psychic Edgar Cayce, and led by Virginia educator Dr. William Moseley Brown, Atlantic University (AU) officially opened its doors in Virginia Beach in September of 1930. Because the University permanently closed a little over a year later, in December 1931, there is little archival evidence of its brief existence, but now a nearly complete collection of the Atlantic Log, Atlantic University’s student newspaper, is available on Virginia Chronicle to provide details about its short life.

In 1924, Morton Blumenthal, a New York stockbroker, met Edgar Cayce, Kentucky-born psychic and “medical clairvoyant.” Nicknamed the “Sleeping Prophet,” Cayce entered trance-like states through which a voice called “the Source” spoke to him, providing “readings” on healing, nutrition, dreams, reincarnation, the afterlife, past lives, and future events. His exposure to Cayce led Blumenthal to become fascinated with concepts like psychic development and the nature of consciousness. As the friendship between the two deepened, Blumenthal believed that by combining his capital and Cayce’s psychic gifts, they could together create a hospital where Cayce could heal patients through his readings.

Years before Cayce settled in Virginia, the Source advised Cayce that his most significant work would occur in the popular resort destination of Virginia Beach. In 1925, Blumenthal, hoping to bring his hospital to fruition, bought the Cayce family a home in Virginia Beach on 35th Street between Pacific and Atlantic Avenues and financed the building of the Cayce Hospital, which opened in 1927. Along with the hospital, Blumenthal envisioned a university with traditional course offerings—a “Harvard at the Beach” as he described it—as well as less conventional classes exploring subjects like metaphysics, spiritualism, and esoteric sciences. Blumenthal hoped the university “would be to the academic community what the Cayce Hospital was to medicine.”1

Though inspired by Cayce’s work, Blumenthal never sought Cayce’s council as he moved forward with the creation of the university nor did he include Cayce on his educational board, whose members were to chart the development of the school. “Edgar had no real voice in the board’s decisions,” writes Sidney D. Kirkpatrick in his extensive biography of Cayce, An American Prophet, “but his lack of involvement was neither a matter of his tight schedule at the hospital nor his initial reluctance due to the financial commitment. The truth…was that Morton didn’t consider Edgar an educated man.”2 To lead his university, Blumenthal instead turned to Dr. William Moseley Brown, a professor at Washington and Lee and Republican gubernatorial hopeful who had delivered the dedication speech at the opening of the Cayce Hospital. In September 1929, at Blumenthal’s urging, Dr. Brown agreed to become the university’s first president.

As plans took shape, newspapers from across the state reported on the exciting prospect of an institution of higher learning in Virginia Beach. “The announcement last Sunday that a new University would be constructed and operated at Virginia Beach has aroused unusual interest throughout Virginia,” the April 18, 1930 edition of Wakefield’s Tri-County News wrote. “This interest was enhanced by the simultaneous announcement that the new school would be headed by Dr. William Moseley Brown, recent candidate for the Governorship of Virginia.” Many more reports came from newspapers as far as Bedford, Lexington, and Rockbridge County. Even the Monocle, the student newspaper of John Marshall High School in Richmond, contained articles anticipating the university’s opening.

As early as the initial planning phases of the school, university leaders, specifically Blumenthal and Brown, were at odds over what it should be. With no intention of creating an institution with studies in reincarnation, mediumism, spiritualism, astrology, and psychic research, Dr. Brown instead envisioned a traditional liberal arts college offering standard liberal arts courses. Rumors circulated that the school sought to have a curriculum with New Age leanings, but in an article printed in the Suffolk News Herald on April 16, 1930, Dr. Brown called the idea “preposterous.” Knowing, though, that he needed Blumenthal’s financial support, Brown did insinuate that there might be a department with “instruction [that] would be the same as conducted by the American Society of Psychic Research as taught for 40 years in many of the larger scientific institutions of the country.” While all involved agreed on the name of the university—it would be called Atlantic University (AU)—there were serious disagreements over more important aspects of the school, like its curriculum and finances. “Lack of cooperation,” writes Kirkpatrick, “especially in regard to financial matters—continued to be a source of great discord as Atlantic University came closer to opening its doors.”3

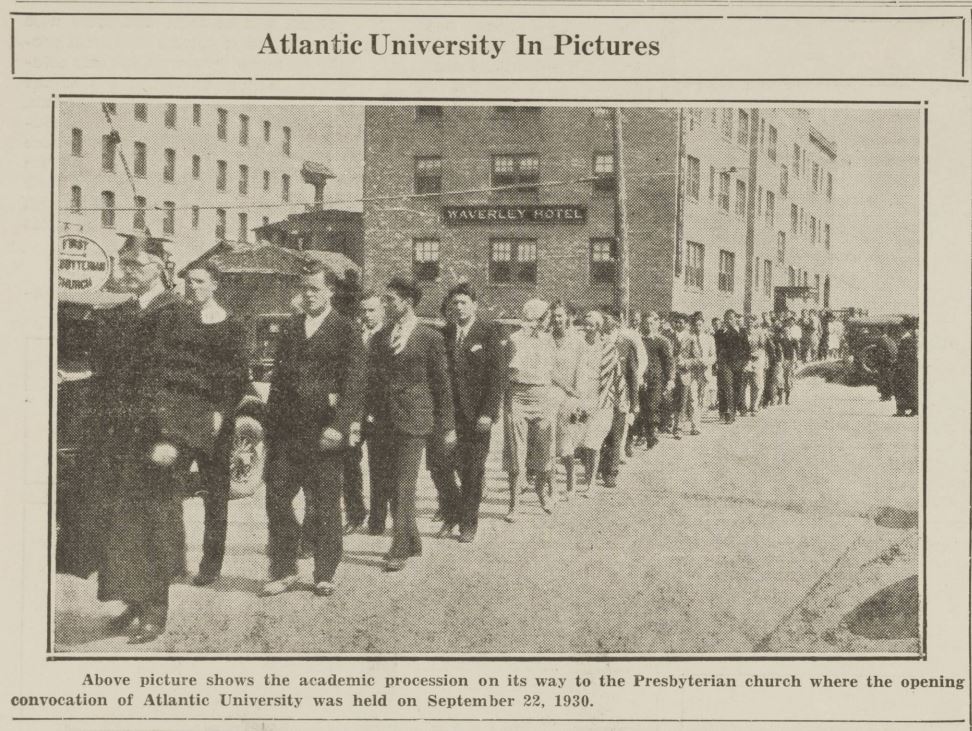

AU’s first session in September of 1930 had all of the trappings of an established Virginia university, with a distinguished president at the helm, a roster of noteworthy professors, a men’s football team (the Sea Dogs), a women’s soccer team (the Mermaids), a school band and theatrical group, clubs, fraternities, student council, and even a mascot, Oscar the Dog. Upon opening, though, it did not yet have its own buildings, so classes took place in rented office space and student housing was provided by local hotels along Virginia Beach’s boardwalk.

On November 14, 1930, AU published the first issue of its weekly student newspaper, Atlantic Log. It included a message of greeting from President Brown and contained a front-page article on the first editor chosen for the paper, J.A. Rosser of Marion. The Log provided an array of school-related information including professor bios, student council news, fraternity news, lecture opportunities, student activities, photographs, and sports news. It also contained regular columns like “The Mail Box,” “Light Whines and Jeers,” “Society,” and “Spindrift.” The glossy student newspaper quickly gained attention and on November 18, 1930, after only one issue had been published, the Lexington Gazette wrote that it “took the initial trophy among junior college and preparatory school newspapers.” The Atlantic Log provided absolutely no indication that AU was anything other than a standard liberal arts university and only one article, written in the paper’s first issue, mentioned a local Bible class taught by Cayce.

Soon after AU’s opening, the combination of continuing disagreements between Blumenthal and President Brown and the previous year’s unprecedented stock market crash led to immediate financial difficulties for the school. In January 1931, only four months after the inaugural semester kicked off, the Gloucester Gazette disclosed that AU was in serious financial trouble, reporting that the “entire faculty has agreed to accept a 50-per cent salary cut for the remainder of the year.” Such drastic cost cuts did not bode well for the university’s future.

Dr. Brown’s cost-cutting measures to save AU were to no avail, as Blumenthal was no longer able to or interested in providing financial support to the school he had initially conceived. In spite of AU’s difficulties, the Atlantic Log never contained articles even remotely hinting that the school might close. As late as October 1931, AU had approved a new school of optometry and an article from the Hopewell News, printed on November 13, 1931, wrote that AU Professor Otto Willa Ulrich was organizing an expedition to the Amazon to collect specimens for the school’s museum, not yet constructed but “plans for which are now under way.”

Only a month later, on December 17, 1931, the Virginia Star of Culpeper conveyed that AU’s chances of survival looked bleak. “News dispatches of yesterday,” it reported, “carry a sad item in regard to Atlantic University, which, it seems, is unable to meet its obligations and a receivership is predicted.”

The Lexington Gazette also reported that the school might “be able to escape from the labyrinth of money troubles…but the future of the university, in Mr. Blumenthal’s words, is ‘very, very problematical.’” On December 24, 1931, the Rockbridge County News informed its readers that the school was filing for bankruptcy.

With a lifespan of slightly more than a year, AU’s faculty and students suddenly found themselves without a university. On January 14, 1932, an article in the Suffolk News Herald reported that thirty AU students and some of its faculty would move to Elon College in North Carolina while the Farmville Herald wrote that the Farmville State Teacher’s College “received 18 students from Atlantic University.” Dr. Brown’s employment plans, as reported by the Suffolk News Herald of May 9, 1932, would be to take the position of provost of the University of Guadalajara.

The Cayce Hospital, another casualty of the Depression, also closed only a few years after opening. In 1931, Cayce supporters founded the Association for Research and Enlightenment (ARE), which still operates in Virginia Beach today, near the site of the original hospital. According to the ARE website, its mission is to provide “body-mind-spirit resources for individuals to explore meditation, intuition, dream interpretation, prayer, holistic health, ancient mysteries, philosophical concepts, such as karma, reincarnation, and the meaning of life.” Who knows what Atlantic University might have become had it continued on, but the Atlantic Log is an illuminating artifact of what it was during its brief existence.

Footnotes

[1] Sidney D. Kirkpatrick, Edgar Cayce: An American Prophet (New York, New York: Riverhead Books, 2000), 413.

[2] Kirkpatrick, 414.

[3] Kirkpatrick, 421.