In June 1800, an enslaved man named Bob was apprehended and jailed in the city of Richmond. Bob was not from the capital city. He was from Goochland County and his enslaver Thomas Woodson had allowed Bob to travel to Richmond to find additional work. Bob’s wife lived in Richmond and Woodson thought it worthwhile to accommodate Bob’s wishes to work closer to the city where his wife lived.

Earlier that year, Woodson had written to a man named Samuel Pinter expressing Bob’s situation and recommending him as a good wagon driver. Perhaps Woodson wanted to prevent Bob from being interrupted in his work—having a spouse in Richmond would cut into Bob’s work time and the labor Woodson could receive. Would allowing him to hire himself out to other individuals be a solution?

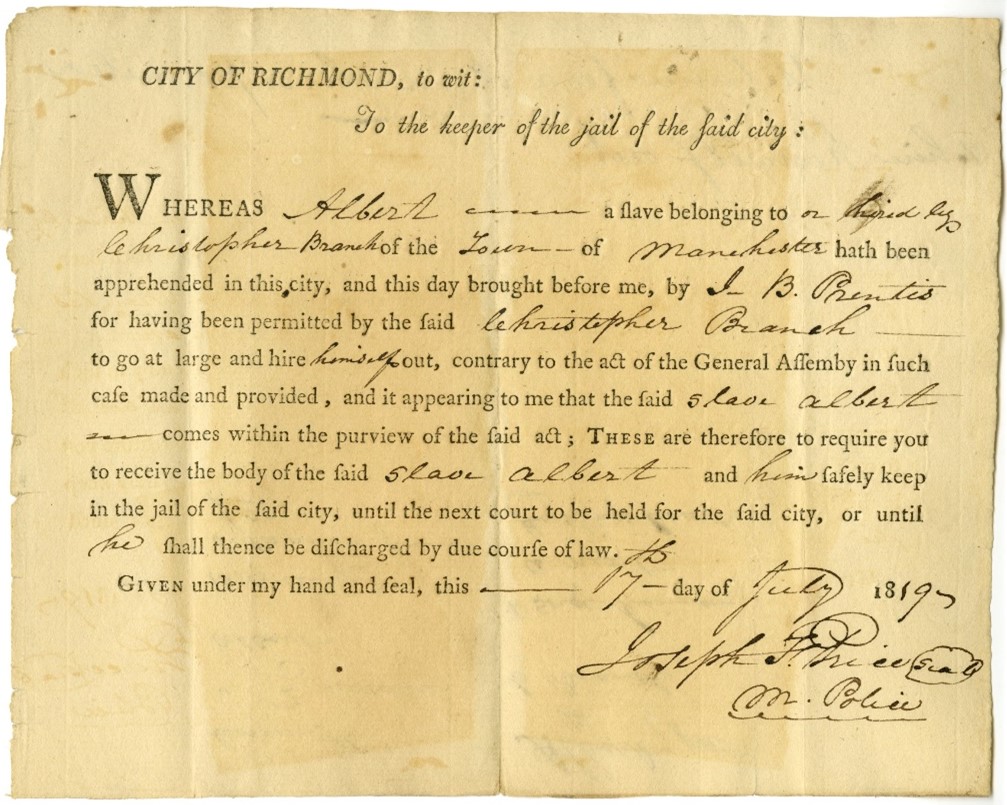

The letters that Woodson wrote on Bob’s behalf were included with the warrant for Bob’s detainment in the criminal case files. It’s possible that Bob carried the letters with him as he traveled around Richmond with the expectation that he would be stopped and asked to explain himself. Regardless of Bob’s explanation however, “going at large” as an enslaved person was a crime in Virginia as of the year 1793.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the practice of hiring one’s own time became nearly synonymous with urban centers throughout the South.1 It was often abbreviated in legal documents as “going at large” or acting as a free agent. Enslavers from rural areas surrounding cities allowed their enslaved people to hire themselves out in places with more opportunities for work—often industrial areas. Growing concerns over Black mobility and autonomy caused Southern city officials to enact measures of control.2 Officials in New Orleans, for example, required enslaved people who were hired out by the day to wear badges.3 Virginia also reacted. In 1793, the General Assembly passed a law “to restrain the practice of negroes going at large.”4

The Richmond City Hustings Court records provide a particularly large dataset to examine the policing of this crime. Enforcement ebbed and flowed throughout the early nineteenth century, but by the late 1840s and early 1850s, records indicate an increased anxiety around people of color in the city.5 The laws tell a similar story. In 1857, the Richmond City Council adopted a set of laws and titled it “Ordinance Concerning Negroes.” According to historian Richard C. Wade, the council had taken older provisions, added a few new ones, and dropped several others to create this seven-page document recorded in the Richmond City Council records (now housed at the Library).6 In addition to restrictions around where Black people were allowed to walk, smoke, live, and exist, white officials also included explicit rules prohibiting enslavers from allowing their enslaved people to hire themselves out or “receive the price of his hire” or “pay for his board.”7 Two years later, in 1859, the City Council published rules that required all those who hired enslaved people to register each individual.8

The Hustings Court records begin around 1784; records of enslaved people “going at large” begin in 1790 and continue through the end of the Civil War. If an enslaved person was jailed for going at large, enslavers were required to pay a fine and the cost of jail fees to discharge them. In some instances, if an enslaver did not show up and “claim” their enslaved property, authorities sold the individual at public auction. Dinah, for example, was advertised for sale when her enslaver James Swain failed to pay the $10 fine releasing her from jail. Apparently, city officials couldn’t get a bid and Dinah was discharged several days later.

“Informants” could receive a cash reward for snitching on enslaved people who they suspected were traveling at large or trying to hire out their time. In 1844, Archibald Wilkinson was set to receive two thirds of the fine charged to the enslaver Francis Taylor for allowing his enslaved man Joe to hire himself out. Wilkinson shows up in other criminal trial papers as an informant. In 1856, he reportedly found two enslaved people hiding on a vessel that free man Lott Mundy was trying to steal North to freedom.9

Details provided in the indictment papers provide a glimpse into the lives of both enslaver and enslaved people living and moving in these urban spaces. In March 1827, John Timberlake was charged with allowing his enslaved man York Oliver to sell goods at the “Old Market” in Richmond. He submitted a bill of exception to the charge which described the following:

“a slave named York Oliver was arrested…near the Old Market in Richmond in the act of opening oysters, several other blacks being with him, some of whom were known to the said witnesses to be slaves; that the slave York aforesaid to be directing & superintending the others…the said witnesses further proved, that the slave York Oliver, has been for the last two or three years, going about the market in the City of Richmond, trading in selling first, crabs & chickens & other articles usually sold in the market…John Timberlake claims the said man named York Oliver as his slave & property & that John Timberlake, resides at the Toll House on Mayo’s Bridge about a half a mile from the place where the salve aforesaid was arrested by the witness…”10

Apparently Timberlake had already been charged and fined with allowing Oliver to travel at large and sell in the market place. He was fined again for $35. It’s unclear what happened to Oliver and his business at Old Market as a result.

Other case documents about going at large include the “slave pass” or the note of passage that the enslaver or hirer provided to the enslaved person.

As these hiring practices became more common and more complex, so did the chain of responsibility. In 1809, James Bailey of Hanover County hired out his enslaved man Peter White to Jesse Franklin, who lived in Richmond. During his time in Richmond, Franklin must have allowed White to hire himself out in the city. Although it was Bailey who legally owned White, Franklin, the hirer, was charged and therefore responsible for paying the fine. In 1823, William A. Parker, was charged a $20 fine for permitting enslaved man Sawney to go at large. Sawney was legally owned by Patsy Hunter who lived in Essex County. The clerk who wrote the indictment seemed unclear on who was actually responsible for permitting Sawney to act as a free agent.

In rare cases, court papers will include statements written on behalf of the enslaved defendant. Fed up with repeatedly bailing Jacob out of jail, Mr. Wilson Allen attempted to explain the enslaved man’s situation to the court. He places the onus of the crime on Jacob’s enslaver who refused to adhere to the laws around hiring out:

“I have spent between 50 to 100$ in relieving Jacob at various times from situations similar to the one in which he is now plac’d & feel no disposition to go farther. As he may be useful to Mr. Adams perhaps it will be well for him to advance what may be necessary to releive [sic] Jacob & reimburse himself from the hire. Should Mr. A. not feel dispos’d to do so—the law must be pursued. By an act of the last session the court has a discretionary power given them of either selling the negro or imposing a fine on the person permitting him to hire himself. In the case in question I suppose the court would impose the fine because the slave belongs to an infant & is plac’d in his present situation by the act of the Guardian. Another reason for imposing the fine is that the same person has frequently committed a similar offense & has as often been warned of the consequences—he however continues in the same loose way of managing the negroes of his ward. The person to whom I allude is Mr. Lyddal Apperson of New Kent Guardian to Samuel Allen Apperson. If Mr. Adams declines taking Jacob out of jail be so good as give this letter to Mr. Marshall who is the Comth’s Attorney in the city court.”11

Mr. Wilson Allen’s letter must have persuaded officials—the enslaver (supposedly Mr. Lyddal Apperson) paid the fine and Jacob was released.

If you’d like to do your own research around policing this practice, you can search the Virginia Untold database in a few different ways. Charges for the crime “going at large” show up in records known as Commonwealth Causes, or criminal trials, involving enslaved people. We’ve fully transcribed many of the Commonwealth Causes and for the ones we haven’t, we’ve tagged each record for the specific charge, which means you can search this phrase (“Going at Large”) in the search bar. We’ve just uploaded an additional 964 Commonwealth Causes from Richmond City from 1834-1860 and over 1,000 more Richmond City Commonwealth Causes are on their way.

Footnotes

[1] John J. Zaborney, Slaves for Hire, 66.

[2] Richard C. Wade, Slavery in the Cities, 48-52.

[3] Ibid, 40.

[4] We’ve written extensively on this law and the resulting documentation and policing in several blog posts. For more see: https://uncommonwealth.virginiamemory.com/blog/2022/03/30/free-negro-registers-from-virginia-untold-now-available-on-from-the-page/ or https://uncommonwealth.virginiamemory.com/blog/2022/11/30/his-claim-to-be-free-is-clear-unquestionable-free-black-virginians-at-large/

[5] Jail reports from Richmond City demonstrate that the city sergeant was arresting ten times as many free Black individuals in the second part of 19th c. Records document 68 people jailed for want of free register papers from 1815 to 1845 compared to 725 people jailed between 1845 and 1865 (a tenfold increase).

[6] Richard C. Wade, Slavery in the Cities, p. 106-109.

[7] The Charters and Ordinances of the City of Richmond, with the Declaration of Rights, and Constitution of Virginia, 1859, 193-201

[8] The Charters and Ordinances, 200-201.

[9] Commonwealth vs. Lott Mundy, 1856

[10] Commonwealth v. John Timberlake, 1827

[11] Commonwealth v. Jack, 1808

Citations

Wade, Richard C. Slavery in the Cities. New York: Oxford University Press, 1964.

Zaborney, John J. Slaves for Hire: Renting Enslaved Laborers in Antebellum Virginia. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012.

The Charters and Ordinances of the City of Richmond, with the Declaration of Rights, and Constitution of Virginia. Richmond, Ellyson’s Steam Presses: N.p., 1859. Print.

Sides, William. et al. “Map of the City of Richmond, Henrico County, Virginia.” Baltimore: M. Ellyson] 1856, Print.