Mob violence against perceived threats to a local community has been a staple of US history, with its long tradition of vigilantism and “popular justice,” especially in the American Frontier. At the end of the Civil War, however, lethal mob violence became increasingly racialized in the South, targeting especially newly freed Black men. While rarely associated with this practice, lynching in Virginia also became a formidable instrument to oppress and terrorize African American communities. With the end of Reconstruction, lynching in the South became a pervasive form of extra-legal, lethal punishment for people accused of serious crimes, or even for violating racial norms. As a tool of racial repression and white supremacy, lynching wasn’t just a way to punish alleged “Black criminals,” though; crucially, it was a form of racial terror to send a message of intimidation to Black communities. Moreover, lynching mobs enjoyed at least some level of support by the white community they hailed from, and virtual impunity from the legal and political system. According to various estimates, between 3,000 and 4,000 Black people were lynched in the South between 1878 and 1940.

Until very recently, lynching was a mostly forgotten page of U.S. and Virginia history, the impact this barbaric practice had on African American communities erased from our collective memory. History textbooks and curricula tend to dedicate little to no attention to how lynchings terrorized Black communities for decades. In the past few years, however, there have been several initiatives in Virginia to address this erasure and confront our past of racial terror, including the History of Lynching in Virginia work group established by the Virginia General Assembly in 2018.

As a researcher of racial violence, I have developed over the last several years a digital history project called Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia to document with primary sources all the lynchings that took place in the Commonwealth between 1866 and 1932. Released in 2018, Racial Terror provides the most complete inventory of people lynched in Virginia with detailed information about the race, gender, age, accusation of each lynching victim, and the location where the killing took place. For each person lynched, the website devotes a page describing the events that led to their murder and its aftermath (for instance, read here about the 1878 lynching of Charlotte Harris in Rockingham County). The overwhelming majority of lynching victims in Virginia were Black men (93 out of 115, 82%), often accused of committing a violent crime against a white person. Twenty lynching victims were white men. Two women, one Black, Charlotte Harris, and one white, Peb Falls, were also lynched, both in Rockingham County in 1878 and 1897, respectively.

By compiling and making accessible a comprehensive account of Virginia lynching victims, the Racial Terror project aims to offer students, scholars, and local communities the tools to explore these neglected stories of mob violence. To tell these stories, often removed from local histories, the site relies on primary sources, especially newspapers – the main source of information available to study lynching. The website hosts a database with more than 600 news articles, mostly from historical Virginia newspapers, covering lethal mob violence in the Old Dominion. Importantly, this project was made possible thanks to several undergraduate research teams at James Madison University (JMU).

Since 2017, I have regularly taught JUST 400, the capstone course for the Justice Studies major at James Madison University (JMU), as a research-intensive Senior Seminar on Lynching and Racial Violence. Students in this course typically dedicate about four weeks during the semester to conduct one or more research projects related to the history of lynching and racial violence in Virginia. Every year, students work as research teams and are assigned weekly research assignments. Depending on the assignment and project, students work individually or as part of a small group. Over the years, students in this course have conducted a variety of projects on primary sources related to the history of lynching in Virginia. For instance, students have used online newspaper repositories such as Chronicling America and Virginia Chronicle to collect, organize, and classify the hundreds of articles that populate the Racial Terror website. As white newspapers were biased sources of information about lynching, often justifying and at times even inciting mob violence, students devoted special attention to gathering articles from the Richmond Planet, the leading Black newspaper in Virginia, as well as the Norfolk Journal and Guide.

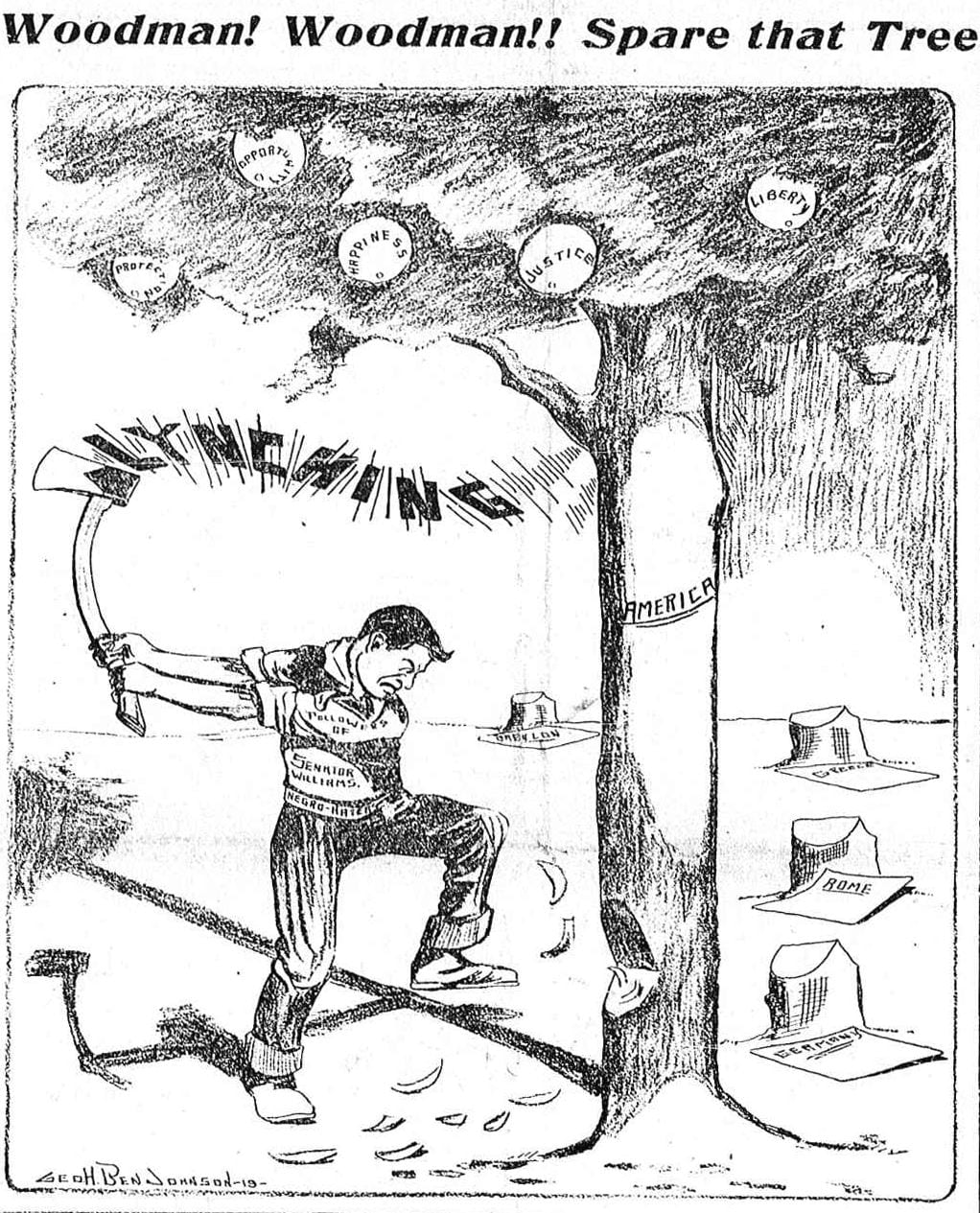

These newspapers, and especially John Mitchell, Jr., the editor of the Planet, represented some of the loudest voices against lynching in Virginia and its apologists, providing a powerful counternarrative to the white media’s construction of lynching [See Figures 1 and 2]. In another project, students geolocated each documented lynching in Virginia, which culminated in an interactive map of lynching in the Racial Terror website that provides basic information about each episode of mob violence and links to the stories of the lynching victims. Based on this student research, the existing inventories of Virginia lynching victims were improved and updated.

Most of the research projects involved the retrieval, use, and organization of news articles, as they represent the main source of information scholars have about lynching. However, newspapers only tell part of the story, and to get a more complete and precise account of these episodes of mob violence, an examination of archives and official documents is needed. Archival sources on lynching are, unfortunately, relatively rare and hard to come by, as most of the time there were no official records that a lynching took place. Like newspapers, these sources are subject to bias, as they are the product of agents of the state with their own institutional priorities, immersed in the white supremacist ideology of the time. As anti-lynching activist and journalist Ida B. Wells succinctly put it, “Those who commit the murders write the reports.” The official investigations of lynchings were particularly important to ensure the impunity of the mobs and the white officials that often failed to prevent a murder; at the end of these investigations, officials would often conclude their report stating that the victims “died at the hand of persons unknown.” In Virginia, very few members of lynching mobs were identified and brought to trial, and only in two cases were lynchers convicted with light sentences (in one case, the murderers were later pardoned) [See Figure 3].

In 2021, under the auspices of the History of Lynching in Virginia Work Group, JMU and the Library of Virginia (LVA) started a collaboration to identify and make accessible the archival sources related to lynching in Virginia. A team of archivists at LVA retrieved and digitized more than 300 pages of documents related to lynching events in Virginia. These archival materials include commonwealth causes, coroner’s inquests, and death certificates. Commonwealth causes are criminal court cases filed by the state government and relate to trials prosecuting individuals accused of violating the penal code. These files include warrants, summonses, subpoenas, indictments, and verdicts handed down by juries and other legal authorities [See Figure 4]. Coroners’ inquisitions investigate the death of individuals who suffered a sudden, violent, unnatural, or suspicious death, or died without medical attendance. Under this category, we can find the inquisition, depositions by witnesses, and summons. Inquisitions provide information about the name of the coroner and the jurors, the name and age of the deceased (if known), their gender and race, and when, how, and by what means these people died [See Figure 5]. Death certificates provide basic demographic information about the deceased and the cause of death. All these documents can provide important details on the lynching victim and how they were killed, as well as the accusation that led to their killing. The identity of the lynchers, however, is almost always unknown, thus leading to impunity for the mob.

In the Spring of 2022, twelve students enrolled in the JUST 400 Senior Seminar formed a research team tasked with transcribing the records that were digitized by the LVA team. As these old documents are often hard to read and are not searchable, transcribing them is a crucial and necessary undertaking to make them accessible to readers. The Justice Studies students thus joined LVA’s Making History crowdsourcing project as part of the larger effort by LVA to enhance “access to collections covering 400 years of Virginia history, people, and culture.”

During the first week of the student’s research project, Sonya Coleman and Lydia Neuroth from LVA held an online lecture via Zoom on “Transcribing Virginia History.” During their presentation, Sonya and Lydia introduced the students to crowdsourcing projects at LVA, the different types of records they would be transcribing, and the legal language that permeated the documents. Most importantly, Sonya and Lydia instructed students on how to transcribe these records, relying on the crowdsourcing platform From The Page. During this lecture, we worked collectively to transcribe one document, thus providing an initial template on how to approach the difficult task of transcribing old records.

For the next several weeks, we used a flipped classroom approach, in which students brought their laptops to class for 75-minute transcribing sessions. Each student was assigned a certain number of records to transcribe individually within a deadline and they used the class time to carry out some of the transcribing; the advantage of this approach was that students could rely on me and other students to ask questions, receive feedback, and “solve” some of the most difficult texts to transcribe. This approach created a dynamic learning environment in which students were helping and consulting each other, as they quickly learned the tricks of the trade of transcribing. For records that were particularly hard to decipher, I created a small team that worked together to transcribe them. When all the records were finally transcribed, I had students review each other’s work, making corrections and leaving notes for each other.

At the end of the research section of the Senior Seminar, we had a debriefing session during which students discussed their experience and challenges in transcribing these records. During the discussion, students voiced their enthusiasm in conducting their research tasks and appreciated how this project was different from other academic assignments they conducted in the past, as this felt to be “real” and akin to solving puzzles. The project also generated a good collaborative spirit in the classroom, as students genuinely took interest in each other’s work and helped each other with the most difficult texts to transcribe. Overall, they had a very positive experience, and knowing that all their work would be made public boosted their commitment and involvement in the project.

After the end of the semester, I worked with Sonya and the LVA staff to further check and revise the transcriptions to weed out any remaining errors. In May 2023, the Lynching and Racial Violence Collection was published online as part of the LVA Digital Collections, making the digitized and transcribed records available to the public. The documents in this collection correspond to lynching victims catalogued in the Racial Terror: Lynchings in Virginia website and are directly linked to the pages dedicated to them. The Lynching and Racial Violence collection at LVA and the Racial Terror website represent two unique sources of primary documents and resources for anyone interested in learning, teaching, and researching about lynching in Virginia.

For far too long, stories of lynching and their impact on Black families and communities have been neglected and purged from both collective and institutional memories in Virginia and, more generally, the United States. History textbooks and curricula have typically overlooked lynchings as a tool of enforcing white supremacy and controlling Black communities through terror. The Racial Terror project and the Lynching and Racial Violence collection are part of a larger scholarly and public effort to reveal and examine the history and extent of racial violence in the United States. As archival scholar Tonia Sutherland noted, “these documentation efforts are also an attempt to create an historical record, eliminating the possibility of erasure and enabling the possibility of justice.”

–Gianluca De Fazio, Associate Professor of Justice Studies, James Madison University