In the excitement of completing our National Archives awarded NHPRC grant, securing a full-time project manager, not to mention participating the Library’s 200th year anniversary, we nearly overlooked another meaningful milestone in the trajectory of Virginia Untold: the project’s 10 year anniversary.

Efforts to illuminate materials about enslaved people in the Library’s collections long predate 2013, but it was this year that marked the grant funded initiative we recognize today as Virginia Untold: the African American Narrative. In that year, we received a generous grant from Dominion Resources to hire two part-time employees, Ed Jordan and Chris Smith, to scan records from our collection related to Black history. Jordan and Smith began digitizing and indexing records from the Free and Enslaved records collections in the Library’ Local Records department (many collections are still referred to by their original title “Free Negro and Slave Records” which archivists are working to repair). We decided to target document types that were unique to the story of Black history in Virginia including petitions to remain in the Commonwealth, petitions for re-enslavement, “Free Negro Registrations”, and “Free Negro Tax” records.

We must give credit where credit is due. In 2011, the Virginia Museum of History and Culture (formerly the Virginia Historical Society) began identifying names of enslaved people in their collections eventually putting them online in what became the Unknown No Longer database (now a part of Virginia Untold). Meanwhile, local records archivists at LVA were finding court cases in which enslaved people were suing for and winning their freedom in our chancery records. To be clear, we did not just “discover” any of these records. They have been here in our archives for decades, overlooked and largely misunderstood by archivists despite their powerful demonstration of challenges and triumphs for Black Virginians. After the confluence of such events (VMHC’s commitment to digitization and the rich narratives resulting from the free and enslaved collections) we knew we had to keep going. We began digitizing coroner’s inquisitions, freedom suits, deeds of emancipation, and indentures of apprenticeship. Shortly thereafter we integrated access to the legislative petitions collection, the first State Records collection in Virginia Untold. The list of Virginia Untold record types only grew from there.

From its beginning, promotion has been an integral part of Virginia Untold’s success.

Three years after the project began, we wrote our first blog post announcing the new accessibility Virginia Untold offered to genealogists, historians, and educators in the form of a website hosted on Virginia Memory (which served the project up until December 2022). Shortly after the website launched in February 2016, the project’s principal founders Greg Crawford and Kathy Jordan were featured on Virginia This Morning to talk about “phase one” of the Virginia Untold project, which at that time was still considered a digital collection. Throughout the years, LVA staff from a variety of departments have shared Virginia Untold at conferences, public libraries, K-12 classrooms, universities, community tabling events, and more.

It’s impossible to quantify how much of the work any one person is responsible for when it comes to our digitization efforts, but we estimate that about 75-80% of the material you see in Virginia Untold today is the result of Ed Jordan’s dedication. It only feels right that we would ask him for his reflections on this project. Jordan began his time at LVA in the Local Records department, before Virginia Untold was an established project. He shares some valuable context about his 10+ years of service.

How did you come to start working for the Library of Virginia? And how long have you been working specifically on Virginia Untold?

I was bored sitting at home after retirement from the Social Security Administration and started looking around for volunteer jobs that I felt I was capable of performing. (I had retired due to health issues.) I had had plans for several types of jobs into retirement but was unable to do any of them due to my medical problems. Thus, I had to rethink my future. I had started doing family genealogical research. It was at one of LVA’s “Straight To the Source” programs where Greg Crawford put out the call for volunteers at LVA. My interest was sparked and I thought that maybe I would enjoy working with these historical documents and maybe it would be something I could do.

I began with Virginia Untold from the beginning in 2013. I started as a volunteer with Local Records for about three or four years prior to this, learning to read old handwriting.

What is your career background?

I am a retired 37+ year Federal employee from the Social Security Administration and a Vietnam-era Army veteran. It was during my Army career (as a security NCO—the person that read every document that came into my agency) that I decided I could do the same type of work as a civilian and work fewer hours with almost the same benefits.

Can you describe one of the most memorable documents/cases that you scanned and processed?

I find the estate inventories [that list enslaved people] to be very interesting. These documents show what a person/family had accumulated over their lifetime and many times how the estate was to be disbursed.

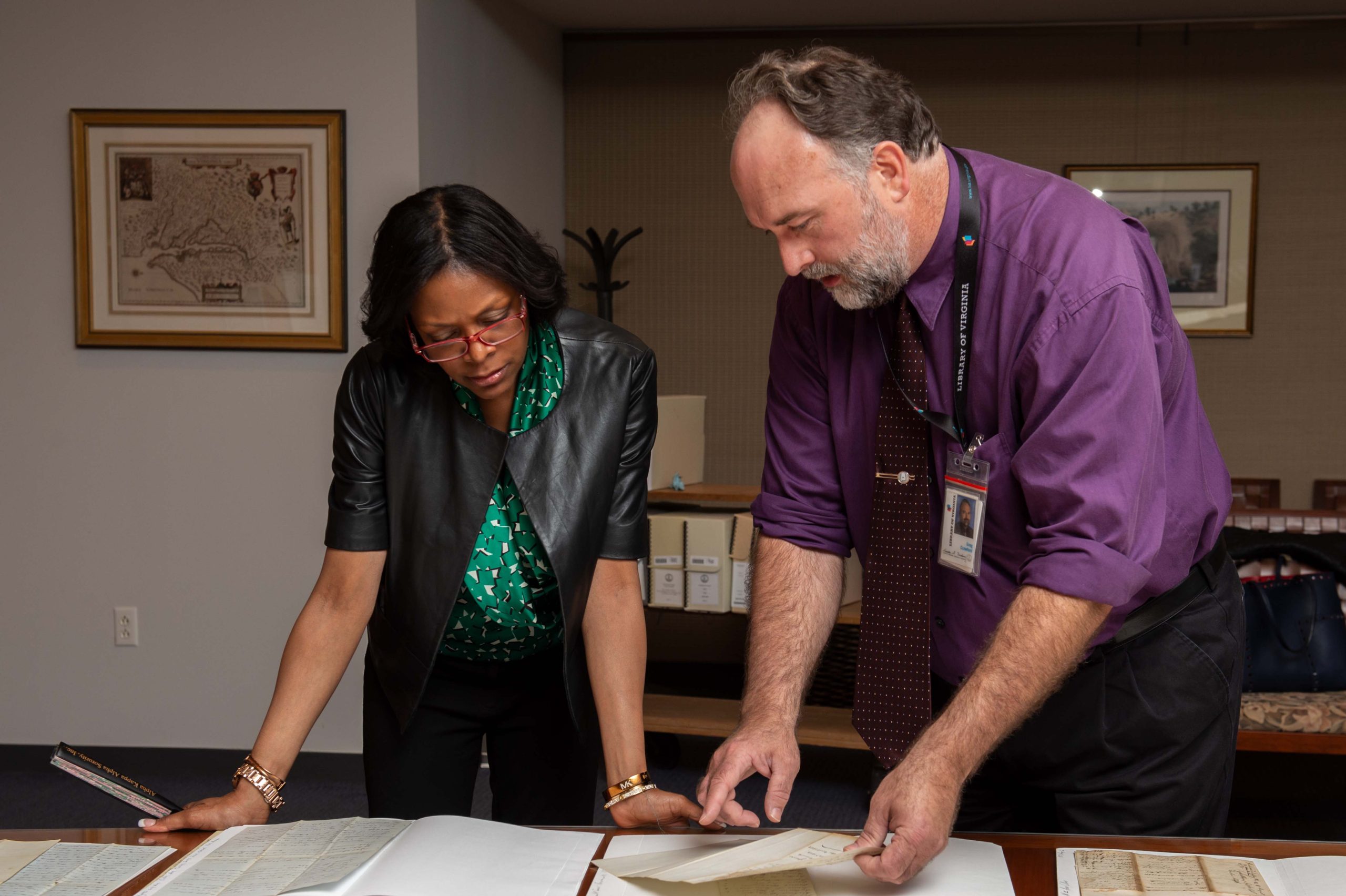

Ed Jordan assists volunteer transcribers at a crowdsourcing session.

John Tyler Community College, Chester Campus, August 2016.

Why does this project matter to you?

I am really glad to “illuminate” these old records. So many members of the public are unaware these records exist, and we are able to fill in a few missing family details.

What has been the biggest change in this project since you started working for Virginia Untold?

The biggest change is in the number and types of records being made available for the program. When I started, we were just doing Coroners’ Inquisitions. Now we have many, many more types of documents being scanned and transcribed.

Where do you see Virginia Untold ten years from now?

Perhaps within the next ten years we can use AI to transcribe documents (maybe by just reading the documents into transcribe, rather than having to type them).

What is your favorite part about this work?

Learning about how the people lived and died. In processing many decades of a particular document, i.e., deeds, you can follow a family from riches to rags and back to riches again.

Anything else that you’d like to share?

Plan ahead for your retirement. Have several or many options available. During many of my retirement seminars (for Social Security) people were always saying “I’m just going to put my feet up and watch TV”. Decide where your interests are and investigate possibilities of a post-retirement job. And what you do after retirement will likely have nothing to do with what you did during your working career.