As my traveling colleague, Tracy Harter, mentioned in her last installment for Records Room Road Trips, we alternate posts between the two of us, and with me up, I am continuing to chronicle my travels, picking up with more western movements.

Kofile Technologies

The week after returning from my second trip to the Henry County circuit court clerk’s office, Tracy Harter and I traveled to the Kofile Technologies facility in Greensboro, North Carolina, to inspect items that had been sent there for treatment. It is one of our responsibilities to travel routinely to the conservation labs to inspect the items sent from the localities and address any issues. Once the records have been deemed satisfactory, we notify the clerks that the items are ready and they make arrangements with Kofile to have them returned. On this trip we inspected a total of 122 items from 11 localities.

Pulaski County

Two weeks after our trip to Kofile in North Carolina, I was back on the road, this time in Southwest Virginia. I had to strategically work out another courthouse visit on my way to my southwestern hub in Abingdon. The unavoidable problem with this strategy is that Abingdon (and Southwest Virginia) is a long way from Richmond. As a result, I don’t get a full day at the first clerk’s office that I visit on the Monday of my travel week, so I wind up visiting them more frequently. That is the case with the office of Pulaski County Circuit Court Clerk Maetta Crewe, which I visited in June of last year, and which will ultimately be on my schedule again next year.

The eight batches of Pulaski County marriage licenses (1908-1923) that I examined were very similar to the marriage licenses that I looked at in Campbell County a few weeks earlier, both in date range and condition. Like the Campbell County marriage licenses (1903-1924), they contained few/no certificates or consents. Also like the Campbell County records, they were folded, bundled, and tightly stored in Woodruff drawers. They also exhibited the same swings in the unevenness in the conditions, changing from good to poor, most likely dependent on the quality of the paper used. Like the marriage records in Charlotte, Campbell, Pittsylvania, and Danville, they will receive the same full treatment: surface cleaned, mended, deacidified, encapsulated, and post bound with tabs.

Dickenson County

Previously in Dickenson County I focused on the oldest land tax books and a run of the oldest deed books that had been stripped with tape (sometimes referred to as sheet extenders) as potential candidates for CCRP conservation grants. Recently, the clerk had procured funding to have over twenty of his oldest land tax books conserved, and with only one remaining deed book “stripped with tape,” I was going to have to seek out other items in need of conservation.

I inquired with the clerk about conserving their marriage licenses. The clerk had had the 1880-1904 marriage licenses conserved previously. Would the post-1904 marriage records be good candidates? He was agreeable, so with the help of his chief deputy, Tracy Baker, we tracked the marriage licenses down in the archival storage area on the floor below. It turns out that the licenses had been scanned in 2011 by the Dickenson County Historical Society and, at one time, had been available on the circuit court clerk’s office records management system. However, when the system was later upgraded, the images were found to be incompatible with the new system.

Because there was no good work area in the basement, I removed the marriage licenses to the upstairs public record room. It is worth mentioning that after they were scanned by the historical society they were stored in unique Christmas-themed shirt boxes and then vacuum-sealed! While I was there, I examined and wrote up condition reports for seven batches of marriage licenses for the years 1905-1915, totaling 2,194 items. Once again, like the other counties before them, they will receive the same full treatment: surface cleaned, mended, deacidified, encapsulated, and post bound with tabs.

Grayson County

On the last day of my first trip working out of Abingdon, I traveled to the office of Grayson County Circuit Court Clerk Susan Herrington, in Independence. I was really looking forward to this trip because on my last visit I had discovered the clerk’s archival storage area on a lower level that I had been exploring on my previous visits. The room was another archival jackpot, loaded with historical records that are perfect candidates for CCRP item conservation grants.

In the past many clerks were under the impression that the bulk of the conservation treatment should be going to the most commonly used items in the records rooms, such as will books and land records like deed books. No doubt, the conservation and maintenance of those volumes is important, however, there were instances where, because of the significance ascribed to them, those records may have in some instances been over-treated. That is to say that, sometimes, clerk and vendor were locked into a routine of conserving only those volumes (whether they might have needed it or not).

When I traveled to the Grayson County circuit court clerk’s office two years ago I had some concerns that we might be running out of good candidates for CCRP item conservation grants. There were a few volumes of loose marriage bonds that had been cellulose-acetate laminated, which were obviously good candidates, but I was not certain where to go next. On that fateful visit two years ago, I asked the clerk if there were any circuit court records down the spiral staircase, and guess what? Jack. Pot.

As time goes by, the archival storage area jackpots become few and far between. So, these jackpot moments, finding a new or hidden storage area, are very exciting. When I made my first visit into this Grayson County jackpot region, it was a literal smorgasbord of historic court records, and when that happens, it is difficult to know where to begin. On this visit, I wrote up condition reports for deed books and, not surprisingly, more marriage records, which finished up my first week in my far-western hub of Abingdon, but I would return.

Smyth County

Two and a half weeks off the road and then back to Abingdon, with my first (half-day) stop being at the office of Smyth County Circuit Court Clerk John Graham, in Marion. Before last year’s visit, the clerk had set aside a number of items that he had designated as a priority. The five volumes all warranted conservation, but I noticed a few other good candidates in the super-clean and well-organized area, and I made sure to note them in my report.

The records that caught my attention on that visit were neatly processed marriage records, dating from the county’s founding (1832), and birth and death records, circa 1853-1896, in Woodruff drawers. The marriage records were in good condition, well organized, and flat-filed. Additionally, the records room manager informed me that they had all been scanned and were available on their records management system, and as a result, the originals were rarely/never requested.

The vital records were a different story. They were so tightly packed into the drawers when I saw them last year, I didn’t even try to pull them out for fear that I might damage them. So I returned with a plan on this visit.

I was permitted to set up shop in a vacant conference room. After they are unfolded, the birth and death records are large, unwieldy, and being brittle, chipped, and tearing, they were not in the best condition. Additionally, they were not organized, sometimes labeled with the date that they were certified and other times labeled for the year they accounted for.

Some were (sewn) bound with other sheets, while others were single loose sheets. On the large conference table I tried to get them all facing the same way, and organized chronologically, all the while fighting to keep the folded documents flattened so that they would not refold themselves (!). It was slow going and, while I love my job, it was not fun. Unfortunately, when it was time to go, I had only gotten part of the work finished. The bad news was that condition reports were only drawn up for four items. But, the good news was that there were a number of items in the queue so there would be more than enough good candidates for the upcoming grant cycle.

Lee County

Next I ventured to the office of Lee County Circuit Court Clerk Rene Lamey, in Jonesville, the farthest far-western destination in my CCRP travels. Wedged in the southwest corner of the state, Jonesville is only a few miles from both Kentucky and Tennessee.

Some clerks’ offices records appear to be nearly complete, while others are less so. Some emphasize certain records, and for no apparent reason, others do not (other than if they survive). Some clerks’ offices hold land and property tax books, while in some localities, those records are found in the commissioner of revenue’s office. Some clerks’ offices have no voter registers, while others do (or may just have a few).

That said, the Lee County’s circuit court clerk’s office has a large number of both land tax books and voter registers, many of which are good candidates for conservation. Unfortunately, both are usually divvied up by booklets into multiple magisterial districts and/or precincts, and if one is not familiar with how the locality, in this case Lee County, is partitioned off over history, it becomes quite challenging to know if all of the records for that year are in front of you (or if some are missing).

I decided to concentrate on the numerous voter registers to see how I might be able to bundle them. The slim booklets range from 16 to 32 pages and would not be good stand-alone conservation items, but how to group them? Anyone who has ever worked with these records knows that there is an obvious (and infamous) 1904 demarcation for the voter register booklets. As a consequence of the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1902, beginning in 1904 there was a conscious effort to disenfranchise the state’s African American voters, and those restrictions were reflected in the titles of the new voter registers for both “whites” and “colored.”

As a result, after much categorization and deliberation I determined to group a selected 12 registers together and title it, “Lists of Colored & White Voters Registered Since January 1, 1904,” which worked out to 504 pages. On this visit I wrote up condition reports for eight items, the bulk of which were deed books in need of rebinding.

Scott County

Speaking of rebinding, the next morning I traveled to the office of Scott County Circuit Court Clerk Mark “Bo” Taylor, in Gate City. The Scott County circuit court clerk’s office has what appears to be a fairly complete run of records, many of which are still in their original bindings. It was not that long ago that the records, which were at times stored in the courthouse bell tower and in the basement of the old jail, were described as being in “deplorable condition.”

While there, Scott County Circuit Court Clerk Mark “Bo” Taylor (right) had a surprise visit from southwest Virginia delegate and Gate City native, Terry Kilgore. The delegate from Virginia’s 1st district (Scott and Lee Counties, part of Wise County, and the City of Norton) said that he appreciated the Library of Virginia’s efforts in “saving Virginia’s history.”

However, after the 1829 courthouse was renovated in 1968 and a vault was added to the clerk’s office, the records were moved there, where they have been rehabilitating ever since. And while over the years a number of items have been conserved, the clerk has taken great pains to see that the volumes in his care are not over-treated, retaining the aesthetic characteristics and historical significance of the record books in their original bindings whenever possible.

Through the routine maintenance, simple issues such as detached pages or spines and broken post binders can be easily remedied before further damage. In some instances the staff from the clerk’s office might have some insight as to which volumes are damaged, but more often than not it is up to me to examine the volumes to identify which might warrant this type of simple conservation.

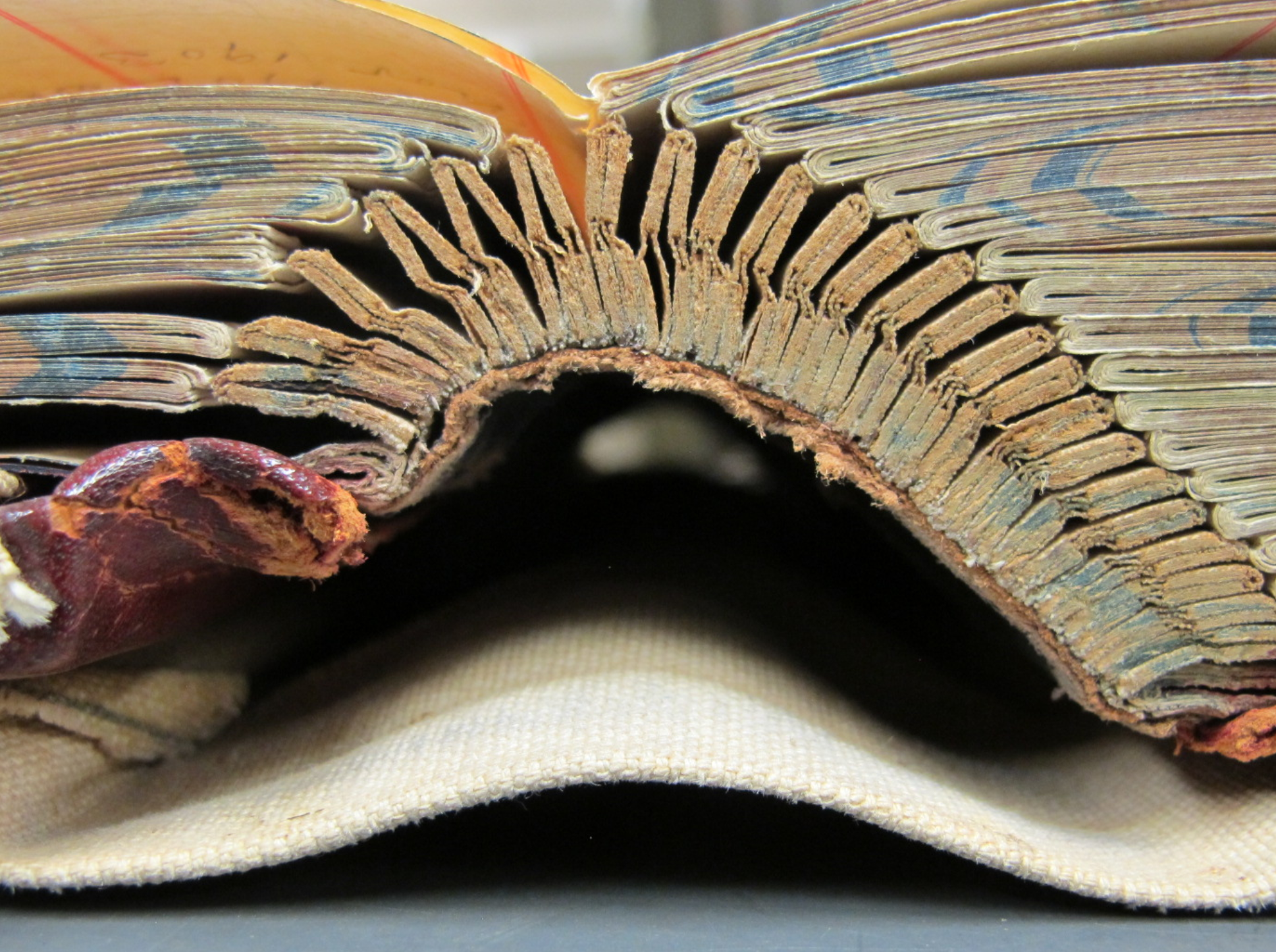

Typical of this type of over-treatment was having the pages of a book cut out at the binding, and then encapsulating each in an archival polyester sleeve before binding in a post binder. Because this “cut and encapsulate” procedure was a common practice with conservation vendors, some clerks got into the habit of having this treatment routinely performed, whether the records actually needed it or not. This meant losing the binding, which might be the 200- or 300-year-old original, which included the boards, pastedowns, and endpapers, all of which may have had textual information or doodling (as clerks were apt to do).

Scott County General Index to Chancery Orders Vo. 1, 1831-1913, with its unique Portland Guard binding structure has a detached (lost) spine and is a good candidate for a simple rebind (left), and some of the old volumes in the roller shelving units in the archival storage area in the Scott County circuit court clerk’s office vault.

Unfortunately, when this process was complete, the original binding materials were usually gone forever. The cut and encapsulate process was so prevalent that today it is not uncommon to see the first 40 or 60 deed books in any county treated in this fashion, prompting one to wonder if they all actually warranted the treatment to begin with. Of course, those first 40 or 60 volumes are some of the oldest records in the county. CCRP consulting archivists operate under the premise that less is more. Whenever we can, we want to preserve/restore as much of the original court records as possible, original binding and all.

On this visit, 13 items were identified for conservation treatment, four of which were requested by the clerk and all of them to be rebound.

Washington County

On the last day of the weeklong visit working out of Abingdon, I began my day with my usual run. And on this morning’s run, I had a little extra time as my short commute was just a brief walk from my overnight accommodations to my 9:00 AM appointment at the office of Washington County Circuit Court Clerk Tricia Moore, in Abingdon.

Localities can have various ill-fated conservation methods from the past that need to be remedied or reversed. In the Washington County circuit court clerk’s office, I worked with two of these: tape-stripped and modern laminated volumes, each with differing results. The tape-stripped volumes, sometimes referred to as sheet extenders, were created (it is assumed) in the 1960s when photocopy machines were becoming common in the courthouses. With tape-stripped books, the pages were cut out and a piece of record paper, the length of the page and formatted for a post binder, was created and affixed with tape to the interior edge where the gutter used to be. This was done, it was assumed, to make the pages easier to remove from the volume for photocopying. Unfortunately, aside from the fact that the binding was lost forever, the tape on the original pages eventually begins to deteriorate and degrade, turning yellow, hardening, and eventually breaking. This becomes more problematic when the tape is covering text on the pages. Additionally, the adhesives in the tape begin to leech out causing the pages to stick together. The only cost effective conservation option is for the volumes to have the tape and adhesives removed and the pages mended, before they are encapsulated and post bound (often doubling the size of the volumes). Unfortunately for the Washington County circuit court clerk’s office, they have quite a few of these volumes.

The 1868 Washington County Courthouse in Abingdon, Virginia on July 13, 2023, while undergoing extensive renovations. It is the only Reconstruction-era courthouse in the state.

We have talked a lot about cellulose acetate laminated volumes in the Records Room Road Trip blog series, but I am not sure if we have mentioned “modern lamination.” Unfortunately, modern lamination, which appears to be something akin to the hard plastic lamination on your driver’s license, has proven to be much more difficult to remove. So much so, that unlike cellulose acetate lamination, at present we are not suggesting a treatment for these volumes. I did a quick inventory of the modern laminated volumes and counted 28. It is sometimes difficult to determine why some localities are burdened with certain of these ill-fated conservation methods and why others are not. The cellulose acetate laminated volumes are more predictable because the main promoter of that form of conservation, William J. Barrow, worked out of Newport News and later Richmond, so it explains why the records within close proximity of those two places will be more prone to having such records. However, when you find a concentration of these other conservation methods, such as tape-stripping or modern lamination, it is more difficult to piece together.

One theory is that these records were treated by itinerant conservators who traveled around the state, setting up shop at courthouses where the clerks were receptive to their wares.

The inventory was made in the hopes that we will one day find a conservation lab with the skills needed to safely remove modern lamination from the volumes in Abingdon, as well as at other courthouses throughout the state. I wrote up condition reports for nine tape-stripped volumes, as well as for three boxes of marriage licenses (1882-1887), which has been an ongoing project of the clerk. Additionally, I wrote up condition reports for two cellulose acetate lamination volumes, the two last cellulose acetate laminated volumes in the clerk’s office.

With the end of this trip to my farthest-west of the western outposts, I returned to Richmond, with only one more planned weeklong visit, next time to Salem.

Roadtrip Roundup

Miles traveled: 1,731 (excluding our trip to Kofile Technologies in Greensboro, North Carolina)

Courthouses visited: 7

Oldest record viewed: Washington County Record of Deeds, 1778-1797

Soundtrack: Anything by Tyler Childers (or Sturgill Simpson)

Best food: Rain Restaurant, 128 Pecan, Luke’s Cafe, and Rooftop at Summers (all in Abingdon)

Virginia landmark(s): Abingdon Muster Grounds and Barter Theatre (both in Abingdon)