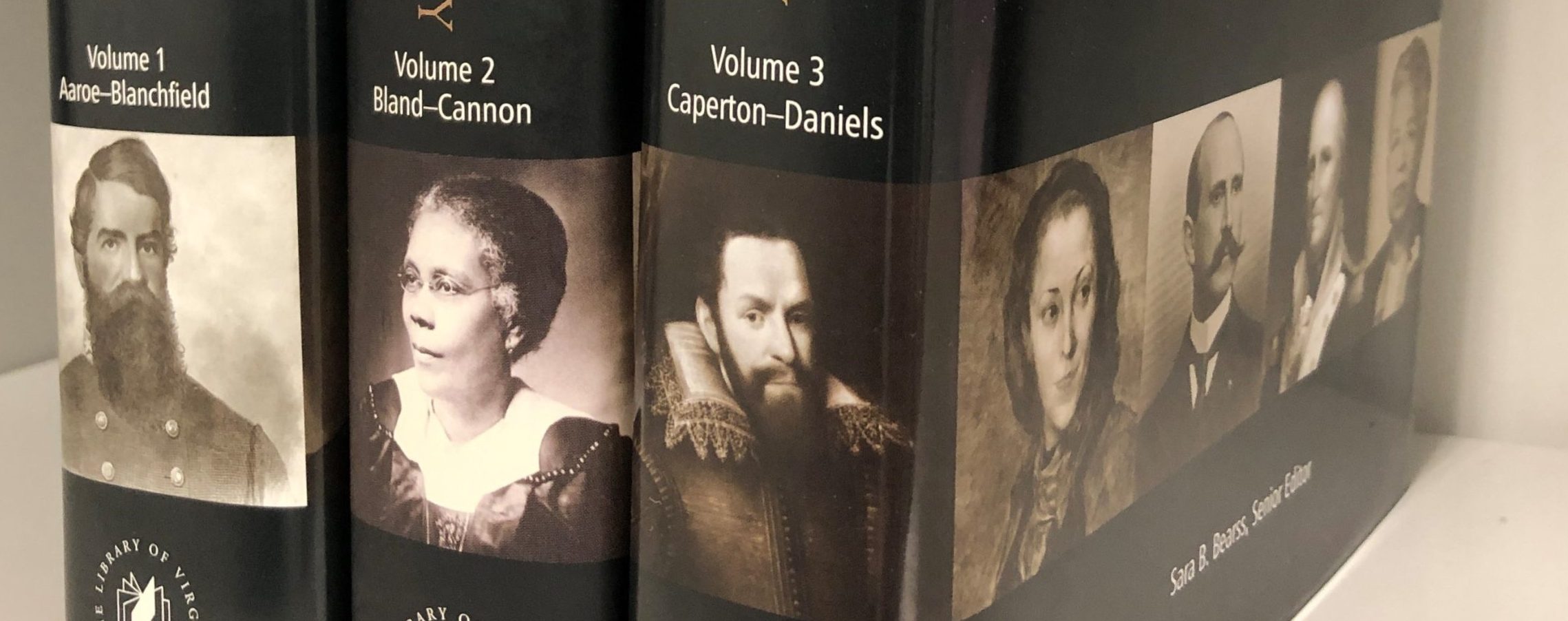

Just like Bob Dylan went electric at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1965, the Library of Virginia’s Dictionary of Virginia Biography (DVB) went digital more than a decade ago and stepped into a new age. Having begun life as a print publication appearing in physical volumes in 1998, 2001, and 2006 containing 1,400 entries for surnames from Aaroe to Daniels, the DVB recently published its 1,000th digital entry (of almost 1,900 total entries to date): African American civic leader Temple Cutler Erwin, written by historian Tameka Bradley Hobbs, our former colleague and current manager for the African American Research Library and Cultural Center in Broward County, Florida.

As the internet exploded as an information resource, many reference works migrated online to increase accessibility. The DVB editors did likewise, digitally publishing both existing print entries and new born-digital entries online, and moving from publishing in alphabetical order to a thematic organization. One of the DVB‘s original goals was to expand the definition of who was significant to Virginia’s history, so the editors began focusing primarily on African Americans and women, who often have been left out of history books.

The DVB partnered with Virginia Humanities’ online resource Encyclopedia Virginia to publish about 200 DVB entries on influential Black Virginians during the post-Civil War decades, including all who served in the General Assembly in the 19th century. As part of the Library’s commemoration of the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the DVB Online also published a series of biographies related to the campaign for woman suffrage. With our 1,000th digital entry, DVB biographies appear on a variety of platforms, including the LVA website, Encyclopedia Virginia, the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission website, and the online History of the Virginia House of Delegates, in addition to being accessible through our DVB search page.

This new digital world not only transformed the publication of the DVB, but it has also changed our research. The biographies have always been grounded in primary sources including vital statistics, census and tax records, organization and business records, family bibles, military records, legislative journals, deeds, wills, other court records, and newspapers. But the explosion of digital resources has dramatically expanded our ability to uncover the unique and often untold stories of underrepresented Virginians.

The Library of Virginia boasts many freely available digital resources, including Virginia Chronicle (newspapers) and the Chancery Records Index (cases of equity), and digital collections such as Virginia Untold (documenting free and enslaved African Americans), all of which have been at the heart of our research.

Public records are often key to finding information about people who didn’t leave behind personal papers like letters, diaries, or other documentation. Chancery cases can be especially helpful in documenting the lives of formerly enslaved Virginians. Several Halifax County cases enabled us to determine which of several African American men named John Freeman was a member of the House of Delegates and to provide more details about his life before and after the Civil War as well as his likely date of death.

U.S. Census records available on commercial sites such as Ancestry (available free to users onsite at the Library) have allowed us to track Virginians across the country over time in a manner that would have been almost impossible if confined to using traditional indexes and microfilm.

We knew little about Maud Powell Jamison other than her suffrage activism in Norfolk and Washington, D.C., but through online census records we could trace her life from her birth in Texas, youth in Norfolk, and her subsequent moves to New York City and to Los Angeles County, where she worked at an airplane parts factory. In the case of Temple Cutler Erwin we found his self-reported birth date in his World War I and World War II draft registration cards, which are among the National Archives and Records Administration records available online through Ancestry.

The exponential increase in digitized newspapers and periodicals at the Library of Virginia has been especially helpful in drawing out a subject’s life story. As the daily record of history, newspapers can help identify often forgotten events. While researching Virginia suffragists we found hundreds of reports about their activities across the state that enabled us to document their work in ways that previously would have involved time-consuming work scrolling through microfilm reels. We found new facts that we hadn’t known to look for. While it was well known that civil rights leader Maggie Walker was a candidate for State Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1921, we had not known just how many women had been candidates for public office in the first election after they gained the right to vote. While researching the biographies of Janet Durham, Eugénie Yancey, and others, we learned that a dozen women eagerly jumped into politics as candidates for the General Assembly and statewide offices in 1921.

Digitized census records made it possible to track Maud Jamison’s moves to locations outside of Virginia.

Similarly, in the case of Temple Cutler Erwin and other African American entrepreneurs, civic leaders, and community activists, digitized Black newspapers provide a wealth of information about businesses, organizations, and individuals. In Hampton University’s Southern Workman, we found many informative articles relating to Erwin’s work with the Negro Organization Society. In the Richmond Planet, we discovered references to Erwin’s Commercial Bank and Trust Company, including its charter by the State Corporation Commission.

The DVB is reframing Virginia history one life at a time and has provided the basis of new scholarship on the woman suffrage movement with the publication of The Campaign for Woman Suffrage in Virginia (2020) and on the experiences of Black Virginians in the post-Civil War period with the forthcoming Justice For Ourselves: Black Virginians Claim Their Freedom After Slavery (2024).

As the Dictionary of Virginia Biography embarks on its next 1,000 digital entries with a focus on Virginia Indians in conjunction with our current exhibition Indigenous Perspectives, online databases such as the Indigenous Peoples of North America (available to Virginia residents with an LVA library card or online account) are helping to document the work of early tribal chiefs in taking action against the commonwealth’s discrimination during the 20th century. With the constant addition of online resources and increased access to our biographies, the internet has transformed the DVB, which continues to reshape the narrative of Virginia history.

-John Deal and Mari Julienne, Editors, Dictionary of Virginia Biography