One hundred years ago this month, the Equal Rights Amendment was first introduced in Congress. After women had succeeded in their fight for voting rights with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution in 1920, some turned their energy and passion to fighting for equal rights.

In July 1923, Alice Paul announced that the National Woman’s Party would begin working for a new constitutional amendment that she proposed: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.” On December 10, 1923, the Equal Rights Amendment (known at the time as the Lucretia Mott amendment) was introduced in Congress.1

The members of the Virginia branch of the National Woman’s Party quickly joined the fight to convince congressional lawmakers of the “necessity of an amendment to the constitution which will give women their full citizenship rights.”2

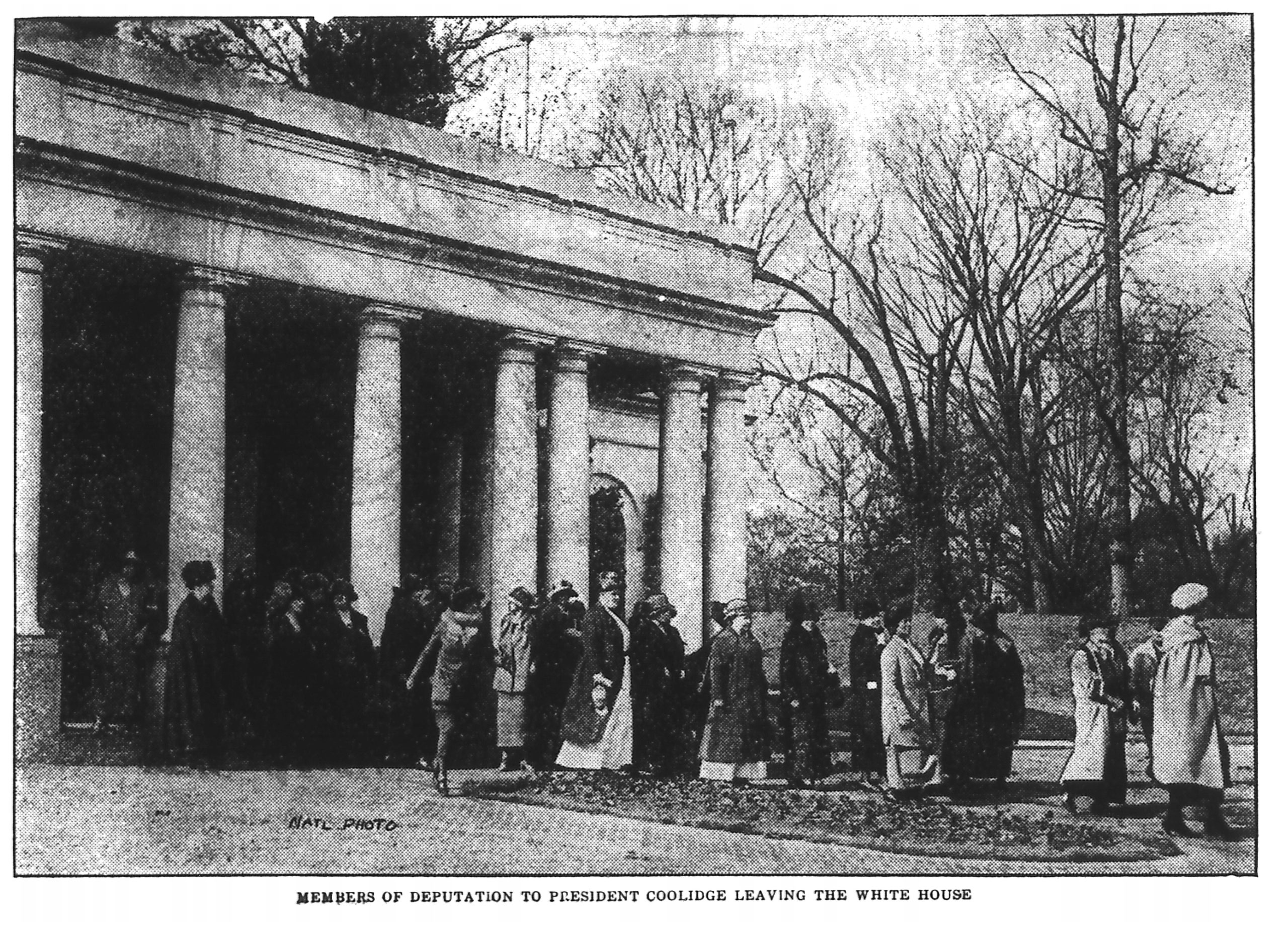

In November 1923, Virginia branch chair Sophie G. Meredith and other members, including Pauline Adams and Julia S. Jennings, were part of a delegation sent by the National Woman’s Party to visit President Calvin Coolidge and urge his support for an equal rights amendment. The Virginia branch lobbied Virginia congressmen to vote for the federal amendment after it had been introduced, and members from Alexandria, Norfolk, Purcellville, and Richmond attended the congressional committee’s first hearing on the amendment in February 1924. The Virginia branch also sent resolutions to the national Democratic and Republican Parties requesting that they endorse equal rights as part of their platforms.3

Not only did the members of the Virginia branch of the National Woman’s Party advocate a federal constitutional amendment, they had already been hard at work for two years lobbying for a similar bill in the Virginia General Assembly. In December 1921, the National Woman’s Party began a campaign in nine states, including Virginia, for the passage of a women’s bill of rights by state legislatures. The Virginia branch eagerly got to work, being “anxious that their State have the honor of being the first Southern State to place its women upon an equality before the law with men.”4

The Virginia branch’s legislative committee secured a favorable ruling from the state’s Legislative Reference Bureau in January 1922 that such a bill would be constitutional. The members then enlisted support from the governor and convinced a state senator and a member of the House of Delegates to introduce the bill in each chamber. When the Senate Committee for Courts of Justice held a hearing in February, more than a hundred women, both in support of and in opposition to the bill, crowded the chamber. The bill “to provide that women shall have the same rights, privileges and immunities under the law as men” did not move past a first reading in either house, however, and was not voted on in 1922.5

The members of the Virginia branch were not deterred by this initial defeat. They returned to their state bill during the 1924 session of the General Assembly even as members campaigned for the recently introduced federal Equal Rights Amendment. Two delegates introduced the bill providing equal rights to women in Virginia on January 28, 1924.6 It was referred to the House of Delegates Committee for Courts of Justice. On February 7, National Woman’s Party members dressed in their white, gold, and purple regalia of the suffrage campaign packed the state capitol for the bill’s hearing. Sophie Meredith spoke in favor of the bill as did Lucy Flannagan, who asked the committee to “give us the surprise of our life” by recommending passage of the bill.7 Members of the Virginia League of Women Voters spoke in opposition to the bill on the grounds that it would have a negative effect on legislation that protected working women. The committee surprised many onlookers when they voted to send the bill to the House of Delegates.8

The Richmond Times-Dispatch disparaged the bill in an editorial, claiming that too many obstacles blocked complete equality and that wives would be forced to work to support their families in the same manner as husbands. National Woman’s Party members quickly responded. Izora De Wolf, of Highland Springs, pointed out that even though a wife “brings in no pay envelope,” the household work she does “day and night (for the mother’s working hours know no legal limit)” contributed to her family’s support. The Virginia branch secretary, Marion Read argued that if a woman’s “services as a housekeeper, manager, purchasing agent, cook, laundress, scrub woman, nurse and mother are not recognized by the law as contributing to the support of the home, then it is time they were so recognized.”9 Such labor by women is still undervalued in the 21st century and would have been worth $1.5 trillion in 2018 if American women were paid minimum wage for their domestic and caregiving work.10

On February 16, 1924, the equality bill met defeat in the House of Delegates by a vote of 39 to 28, and the state senate never voted on it. The first two women serving in the House of Delegates split their vote, with Norfolk delegate Sarah Lee Fain voting for it and Buchanan and Russell County district delegate Helen T. Henderson voting against it. Virginia branch secretary Marion Read expressed the optimism of the National Woman’s Party members that 28 votes in favor of equal rights was “a long step toward victory.”11 The Virginia branch continued its fight. Similar bills were introduced during the 1926, 1928, and 1930 General Assembly sessions, but were killed in committee each time. Equal rights bills do not appear to have been introduced at subsequent Assembly sessions.12

Little did the members of the Virginia branch realize in 1924 that it would take almost a hundred years for Virginia’s General Assembly to vote in favor of equal rights for women. The Virginia branch, and eventually the Virginia League of Women Voters, continued to lobby the president and members of Congress for the federal Equal Rights Amendment,13 which was introduced in each Congress until 1972 when it was sent to the states for ratification. Virginia became the 38th state needed to ratify the amendment on January 27, 2020. Virginia’s ratification has not yet been certified as of 2023, and the fate of the ERA remains in the hands of the courts and Congress. For more of the ERA story and the work of Virginia women who fought for its ratification later in the 20th century, visit our previous UncommonWealth blog post: Unfinished Business: The Fate of the Equal Rights Amendment.

Footnotes

[1] See “From Nineteenth Amendment to ERA,” Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/women-fight-for-the-vote/about-this-exhibition/hear-us-roar-victory-1918-and-beyond/ratification-and-beyond/from-nineteenth-amendment-to-era/#:~:text=Drafted%20by%20Paul%20as%20early,regulations%20designed%20to%20protect%20women); also “History of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)” (https://www.alicepaul.org/equal-rights-amendment-2/). It was introduced in the Senate on Dec. 10 (Congressional Record 65, pt. 1, 150) and in the House of Representatives on Dec. 13 (Congressional Record 65, pt. 1, 285).

[2] Richmond News Leader, Sept. 22, 1923 (https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=NEL19230922.1.6)

[3] Norfolk Post, Nov. 17 1923; Richmond News Leader, Feb. 5, 1924 (https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=NEL19240205.1.4); Report of Secretary Va. Branch National Woman’s Party, 1923–1924, in Marion Read Scrapbook, The Valentine, Richmond.

[4] Maryland Women’s News 10 (31 Dec. 1921): 308; Richmond Times-Dispatch, 12 Jan. 1922 (https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=RTD19220112.1.14)

[5] Richmond Times-Dispatch, Jan. 21, 1922 (https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=RTD19220121.1.13); Culpeper Virginia Star, Jan. 26, 1922 (https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TVS19220126.1.1); Fredericksburg Daily Star, Feb. 6, 1922; Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia (1922), 290 (quotation); Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Virginia (1922), 90; Richmond News Leader, Feb. 21, 1924 (https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=NEL19240221.1.1).

[6] Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia (1924), 99.

[7] Winchester Daily Independent, Feb. 11, 1924 (https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=DIN19240211.1.3)

[8] Richmond Times-Dispatch, Jan. 12, 1924; Richmond News Leader, Feb. 8, 1924 (https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=NEL19240208.1.4)

[9] Richmond Times-Dispatch, Feb. 9, 1924, Feb. 13, 1924 (first quotation), Feb. 15, 1924 (second quotation).

[10] New York Times, Mar. 5, 2020; Oxfam Time to Care, 2020 report (oxfamamerica.org)

[11] Vote recorded in Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia (1924), 324; quotation in Report of Secretary Va. Branch National Woman’s Party, 1923–1924, in Marion Read Scrapbook, The Valentine, Richmond.

[12] Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia (1926), 83 and (1930), 341; Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Virginia (1928), 60. An equality bill does not appear to have been introduced in the state senate during the sessions 1926 or 1930 or in the House of Delegates during the 1928 session.

[13] The language of the amendment was rewritten in 1943 to read “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

Header Image Citation

More than a dozen Virginians were part of the National Woman’s Party delegation, seen here leaving the White House in November 1923 after soliciting the president’s support for an equal rights amendment to the Constitution. (Equal Rights, Nov. 24, 1923, Library of Congress)