Cornbread and cabbage turned lethal for one Petersburg woman, but it was another woman’s need for some chicken feed that exposed the death as something more nefarious than a simple case of food poisoning. Parmelia Williamson became “deathly sick” after consuming what proved to be her last meal on 9 June 1909. Junius Williamson, Parmelia’s husband, first used the word “poison” to describe his wife’s condition because he did “not think she washed the ham as it oughter [sic] have been.” Even Parmelia said “her stomach felt like it did when she was poisoned in the country.”

Attended by her husband and neighbor Delia Brooks, Parmelia was examined by a Dr. W. C. Powell who pronounced it a case of “Cholera Morbus,” but Parmelia insisted, “I have no Cholera Morbus, I am poisoned.”

He gave her a hypodermic injection, put hot water bottles to her feet, and left. As she continued vomiting, her condition worsened, and she threw her arms up and said, “Delia, save me, do not let me die…save me for the sake of my poor little infant baby.” Another doctor, James E. Smith, was called and pronounced that Mrs. Williamson would not live two hours and that she had been poisoned by arsenic or “Paris Green,” a compound used as an insecticide for produce in the 1900s. After she gasped her last breath, Mr. Williamson threw himself across the bed and exclaimed, “Oh Lord, what will I do with my baby.”

Parmelia’s death was almost written off as an unfortunate tragedy caused by the improper handling of food. But Delia Brooks needed that chicken feed. In the weeks before her death, Parmelia had borrowed some meal from Delia, and Delia was determined to get back the meal she was “owed.” Before Parmelia breathed her last breath, Delia Brooks decided it was the perfect time to ask for the meal she had used to make the cornbread. Delia took it home and fed her chickens only to find them all as dead as Parmelia the next morning. She asked Junius Williamson about having Parmelia’s stomach analyzed and he objected to it “because Mr. Kersey [Mrs. Williamson’s father] kicked up so about it.” Besides, Dr. H. G. Leigh, the coroner, had told him the cost would be $250, and “if old man Kersey had $250, he could have it done.”

Soon word about the dead chickens got around, and Mrs. Williamson’s brother stated that he “could stand it if his sister died of natural causes,” but not if she had been poisoned. He also claimed that Junius “had tried to poison her once before.” He brought Dr. Smith a small box of the meal that he obtained from Delia Brooks, and Smith tested it and found the presence of arsenic.

A Times Dispatch article dated 13 June 1909 tells what happened next: “Some serious suspicions have been expressed as to the exact cause of her death, some going so far as to intimate malice. In order to settle all questions, it is understood today that the father of Mrs. Williamson, John Kiersey [sic], of Chesterfield County, may have the body exhumed and the stomach examined.” The coroner’s inquisition, held 7 July 1909 at the J. T. Morris and Son Undertaking establishment, examined the exhumed body of Parmelia Williamson. In a detailed letter dated 2 August 1909 to Coroner H. G. Leigh, Dr. William H. Taylor, chemist, explained the completed stomach analysis for Parmelia Williamson and that white arsenic, “the arsenical compound commonly employed by poisoners,” was detected. Since arsenic was a common ingredient in embalming fluid, Taylor also tested a sample of embalming fluid from J. T. Morris and Son and found an absence of arsenic: “It does not prove that the fluid actually used in embalming Mrs. Williamson’s body was free from arsenic. It is now impossible to assure ourselves of this, though it seems probable that it was so.” The embalmer from the funeral home, W. H. MacKasey, confirmed that he embalmed Mrs. Williamson the morning after her death with a “non-arsenical formaldehyde embalming fluid.”

The coroner’s inquest resumed 6 August and found that Parmelia Williamson “came to her death on 9 June 1909 from arsenical poisoning administered by a party or parties unknown.” So was the husband, Junius Williamson, that “party unknown?” On 16 June, Junius was arrested and presented with a warrant charging him with the murder of his wife. But would he ever serve time for his supposed crime?

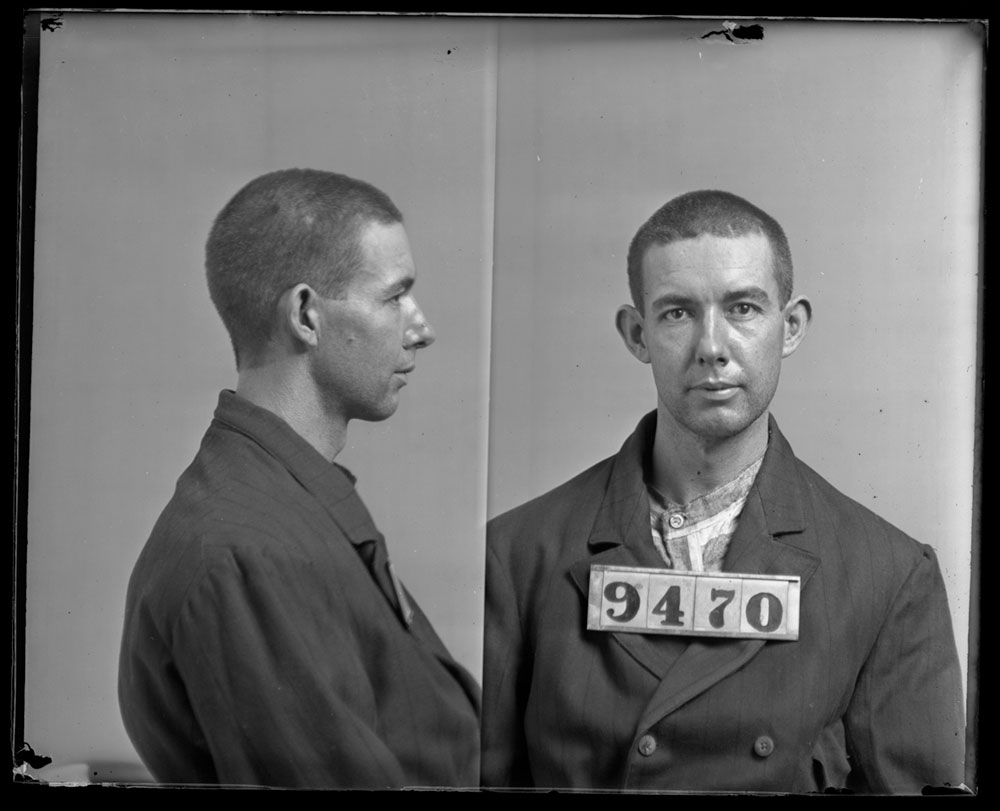

Junius escaped from jail but was located in Fort Russell, Wyoming, having enlisted in the United States Army. According to the 2 November 1909 edition of the Times Dispatch, “he was arrested there, and brought back in his army uniform…Williamson strenuously denies having poisoned his wife, and there is only strong circumstantial evidence to connect him with the crime…Fully 1,000 people went to the depot …expecting to get a glimpse of him.”

Virginia State Penitentiary records show that Junius R. Williamson, alias J. G. Williamson, was admitted on 28 June 1910, sentenced by the Petersburg Hustings Court to 4 1/2 years for bigamy. As it turned out, Williamson already had a wife living in Marietta, Texas, when he married Parmelia. Junius was discharged 26 May 1914. A note in the prison register indicated that he was wanted at the end of his term by the Commonwealth’s Attorney of Petersburg. Was this reference related to the death of Parmelia? Would he finally serve time for his wife’s murder? We may never know because Junius Williamson does not appear in any later prison registers.

The testimony and investigation into the death of Parmelia Williamson, dated 6 August 1909, can be found in the Petersburg Coroners’ Inquisitions, 1807-1947. The collection is open for research and available at the Library of Virginia.

-Mary Dean Carter, Local Records Archival Assistant