Mary Johnston, born 1870 in Buchanan, Virginia, was a prolific author of 23 books, outspoken suffragist, and founding member of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. Her most critically successful books were historical romantic fiction, though her writing also focused on her personal beliefs, including women’s rights, and later, race and lynching.

In 1909, Mary Johnston, Ellen Glasgow, and Lily Meade Valentine founded the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. On November 20, 1909, the inaugural meeting was held at Anne Clay Crenshaw’s home at 919 West Franklin. At the meeting, Valentine was chosen as president by the group of women in attendance.1

Fittingly, the site of this first meeting, purchased by Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in the 1960s, is now Crenshaw House, the home of the department of Gender,

Sexuality, and Women’s Studies.

Not long after this first meeting, on December 12, 1909, the Times-Dispatch published Johnston’s essay, “The Status of Women.” Johnston believed women should gain the vote for multiple reasons, but a common thread in her writing was the idea that throughout human history, men placed an undue burden on women. Johnston expands her theory, writing that long before men had gained social power over women, cavemen had seen the advantages of selecting a mate “not so physically strong as himself, upon whom, therefore, he could impose his will.” In her article, she detailed at length what this “stone” placed on women entailed:

[An] enormous top-heavy mass of conventions, senseless restrictions, superstitions, sentimentalities, mock modesties, rules of conduct dating from nowhere on earth, but her seraglio experience, sequestration from healthful activities, premiums on mental indolence, a vast incubus of bric-a-brac and filigree teachings, of discriminating laws, taboos, taxes, vetoes, and general miscomprehension.

Johnston believed that one step towards relieving women of this oppressive weight was to give them the vote. In “The Status of Women” and much of her writing, Johnston stressed her belief that voting would not draw women away from their duties in the home. Instead, she maintained that women, innately driven to protect their children, would use the vote to further their interests above all else.2

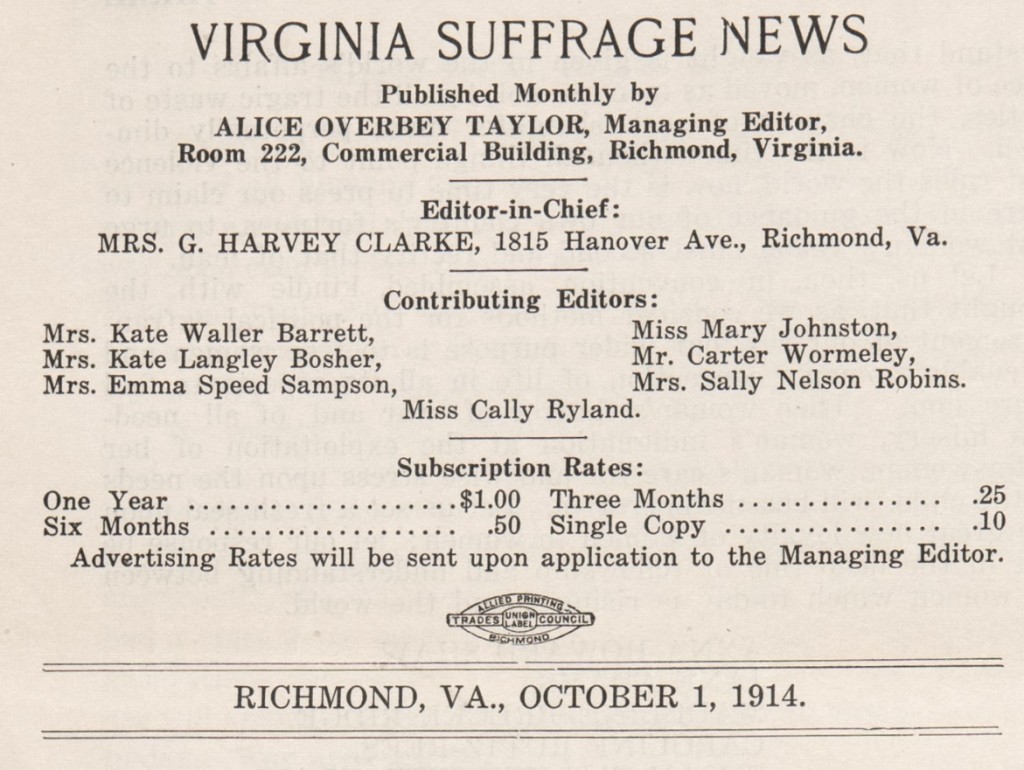

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia published a monthly paper, Virginia Suffrage News, in Richmond. Its October 1, 1914 issue printed Mary Johnston’s essay, “These Things Can Be Done.” The essay is an impassioned argument for why women should be granted equal voting rights. She writes, “In this country, as in all countries, women suffer huge injustices- legal, economic, social, and political,” yet they have no vote, and therefore no voice, to bring about institutional change and undo these injustices. Johnston declared that “[women] are taxed without representation and governed without consent,” ending her essay with the directive: “Women of Virginia, awake!”3

The daughter of a Confederate veteran, Mary Johnston was raised with great reverence for the Confederacy and the South. As an adult, she wrote, “Virginia is my country, and not the stars and stripes but the stars and bars is my flag.”4 Today, Johnston’s racial opinions would fall well outside of the mainstream, but in the early 20th century, these beliefs did not make her an anomaly. She believed in the scientific theory of her time: eugenics. Eugenic theories were believed to be legitimate science in the early 1900s, even receiving praise in Scientific American.5 These eugenic theories influenced Johnston’s drive to secure the vote for women. A 1911 New York Times interview explained “her desire for the advancement of women is for the benefit of the race.”6

Johnston’s later writing shows an evolving opinion on race, particularly her 1923 short story “Nemesis,” published in The Century Magazine. “Nemesis” depicts the horrific lynching of a black man, arrested on little more than suspicion. Johnston details the intense psychological fallout it has on the people involved, resulting in madness and suicide. That year, Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life reviewed the story, saying “The writer shows with her graphic pen the psychological and moral effects of a lynching… Those who have lawlessly wreaked their hatred upon a helpless black victim are themselves consumed by the very human passions which their action aroused.”7 The story made an impression on Walter White, the assistant secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), moving him to tell Johnston he had never “read any story on this great national disgrace of ours which moved me as yours did.”8 While “Nemesis” indicated an evolving attitude, Johnston did not publicly speak out against lynching. Nonetheless, writing an anti-lynching story as a white southern woman was a strong statement in 1923. “Nemesis” was published seven years before Jesse Daniel Ames founded the influential organization, Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching.9

Mary Johnston was a woman of strong convictions. Using her fame as a platform, and the safety of her position of privilege in society, she advocated not only for women’s suffrage, but for an end to the double standards and injustices that women faced daily. She asserted that men, rather than the natural order, were responsible for women’s place as second class citizens. Raised to view the Confederacy with respect and awe, and living amidst the philosophy of the Lost Cause, Johnston’s beliefs regarding race are unsurprising. What is surprising is her apparent willingness to criticize and encourage change in the region she so loved. While an imperfect character in Virginia’s history, Johnston believed in change: in herself, her nation, and her beloved South.

– Olin Johnson, Virginia Newspaper Project Intern

Bibliography

1. “Virginia Suffrage League Meets at Mrs. Crenshaw’s.” News Leader, 23 Nov., 1909, p. 11.

2. Johnston, Mary. “The Status of Women.” Times-Dispatch, 11 December 1909 , p.3C-4C

3. Johnston, Mary. “These Things Can Be Done.” Virginia Suffrage News, 1 October, 1914, p. 2.

4. Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill. “Mary Johnston, Suffragist.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 100, Issue 1, 1992, p. 102

5. “The Early Days of Eugenics.” Scientific American, May 25, 2011.

6. Miss Mary Johnston: A Suffrage Worker.” New York Times, 11 June 1911, p. 8.

7. “Nemesis.” Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life Volumes 1-2. New York: Kraus Reprint, p. 284. 1969.

8. Brooks, Clayton McClure, Samuel P. Menefee, and Brendan Wolfe. “Mary Johnston (1870–1936).” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 20 Mar. 2014.

9. Brooks, Clayton McClure, Samuel P. Menefee and Brendan Wolfe. “Mary Johnston (1870–1936).” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 20 Mar. 2014.

Hi Claire!

Thanks for your piece about Mary Johnston. It has moved me to download a copy of her piece, “Nemesis,” which I’m looking forward to reading.

Best regards,

Jo

Great article Claire. You have a gift.

Fantastic article, Claire! Hoping to see more from your work at the LVA!