The bedrock of the Library of Virginia’s chancery causes collection is the personal story. While most causes share similar documents, topics, and resolutions, each story told is unique. While processing 3,510 Montgomery County chancery causes during a two-year National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant-funded project, former Library of Virginia Senior Local Records Archivist Sarah Nerney and her staff of two,

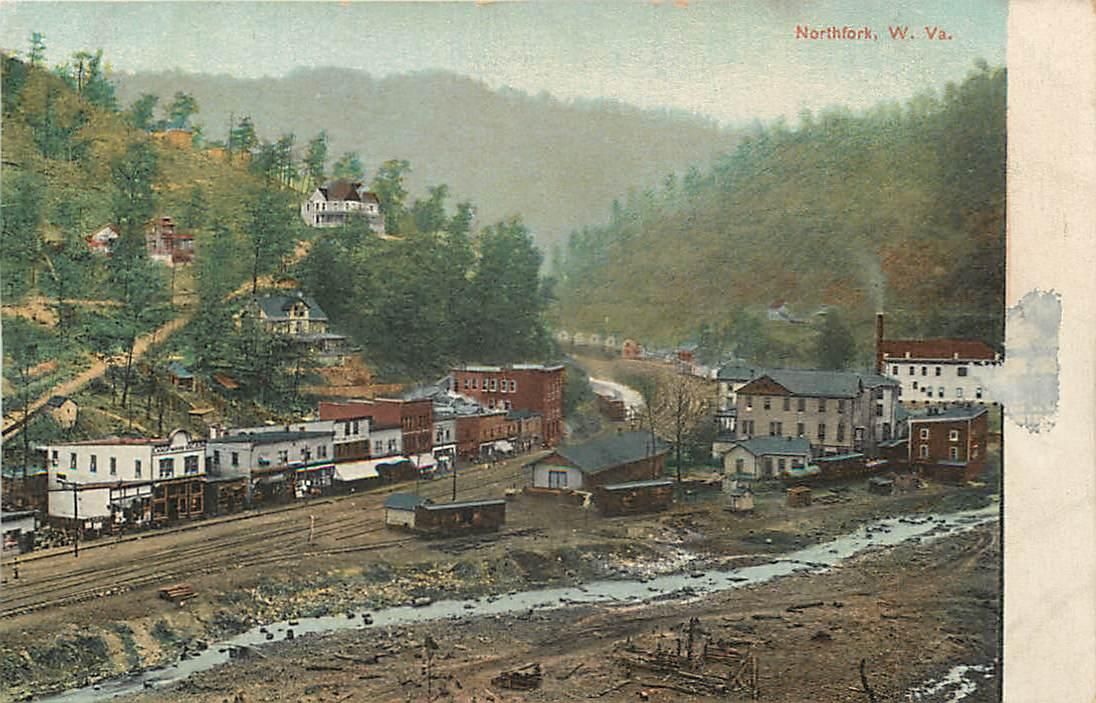

Postcard of Northfork, WV, coal camp just north of Switchback, WV. Courtesy of Pintrest.com

Regan Shelton and Scott Gardner, managed to record numerous noteworthy causes, known in local records jargon as suits of interest. One such suit of interest is Agnes Schaub by, etc. v. Floyd Schaub, 1912-042.

On 15 December 1908, Agnes L. Harrison and Floyd Schaub married in Bristol, Tennessee. As Agnes later recounted, she “was a mere child when she ran away and married… just about 30 days before her sixteenth birthday.” As their marriage license indicates, Agnes was born in Carroll County, Virginia, while Floyd was born in neighboring Pulaski County. For a short time, they live together with “his people” in Carroll County and in Bluefield, West Virginia. Eventually, the couple settled “half-time in Pocahontas, Virginia and half-time in Switchback, West Virginia.”

Agnes acknowledged that Floyd began to mistreat her almost as soon as they were married, and that “on the slightest provocation or without provocation, he would curse and abuse her and threaten to beat her.” She described Floyd as a “shiftless, lazy, quarrelsome, cruel man.” She recounted that Floyd made “little effort to provide [her] with the bare necessities of life,” and that she would have really suffered “if it had not been for what was occasionally sent…by her father, George W. Harrison.” Then, in the spring of 1909, Agnes’s precarious life with Floyd in the West Virginia coal camp of Switchback began to deteriorate even further.

Early in the summer of 1909, Agnes became sick with typhoid fever. She attributed her predicament to a “lack of proper food and care” and “the abuse that her husband had heaped upon her.” In the original bill of complaint filed in the cause, Agnes stated that “when she became helpless … Floyd showed what a scoundrel he was.” He did not give his wife any attention nor did he furnish her with any medical care. He also did not allow her to have any contact with her family.

After three weeks of the debilitating bacterial infection, Floyd Schaub thought that Agnes was going to die and finally notified her mother. As Agnes stated in the cause’s amended bill, “If it had not been for the kindness of neighbors, principally Hungarians, [she] would have died before her mother reached her.” The neighbors provided nursing care and “a lamp to take medicine by.” Agnes’s mother arrived on 26 July 1909 and found her daughter “unconscious and needing every attention.”

Agnes had become so ill that “she had to have the windows and doors left open.” Coal dust settled on everything. Agnes’s hair was so matted to her head that it had to be cut off, and she was too weak to take her medicine. Her mother proceeded to bathe her daughter, and purchase clean bed linen and one dress from the coal camp’s commissary. As there was nothing in the house, she also had to furnish provisions. Addressing the situation in the amended bill for the cause, Agnes relayed that as soon as she began to improve, and her mother spoke of taking her home, “Floyd Schaub threatened to kill her, and her mother as well if she attempted to leave,” vowing to “stamp [Mrs. Harrison] through the floor if she meddled with him.” Eventually, Dr. Hill, the local physician, “had to threaten him with arrest before he would in a measure stop his brutal treatment.”

On 21 August 1909, Agnes was well enough to return to her parents’ home in Carroll County. She never saw or communicated with Floyd again.

Agnes continued to live with her parents, moving with them to Montgomery County in 1910. On 2 April 1912, Agnes filed for absolute divorce from Floyd Schaub. In her original bill, she claimed that she was entitled to a divorce based on “his desertion and unfaithfulness.” However, her attorney failed to prove Floyd’s adultery. She then filed an amended bill on 1 September 1912, asking for a divorce “on the grounds of cruelty, great fear of bodily harm and desertion for more than three years.” Given that he had deserted her and that he “made it impossible for her to live with him,” the court dissolved the bond of matrimony.

By October 1912, Agnes resumed her maiden name of Harrison. Agnes managed to survive a very harrowing experience at a young age. Such tales are all too common in the divorce cases found in chancery causes, and the statistics are just as horrifying today. One in five women and one in seven men have been victims of severe physical violence at the hands of an intimate partner.

Like young Agnes, no one ever knows when he or she may need help or who might step in to provide it. The efforts of her Hungarian neighbors probably saved Agnes from a premature death. Even though foreign-born coal miners and their families may have been viewed with suspicion in the coal camp, their kindness to Agnes proves that human decency knows no national borders.

If you have not already done so, please visit the Library of Virginia’s current exhibition, New Virginians, 1619-2019 & Beyond. The exhibition runs through December 7.

The Montgomery County chancery causes were flat-filed, indexed, conserved, and digitized thanks to generous support by the NHPRC and Montgomery County Clerk of the Circuit Court Erica W. Conner and her staff. To revisit some of the discoveries made over the course of this two-year project, check out some earlier blog posts. The digitized chancery causes are now available on the Library’s Chancery Records Index.

If you or someone you know is suffering from domestic abuse, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE). The International Directory of Domestic Violence Agencies has a worldwide list of helplines, shelters, and crisis centers.

–Callie Freed, Local Records Archivist