Shortly after we published our story about William Pemberton, Lisa Denton from Henrico County Recreation and Parks reached out to me to share about her work uncovering information about Pemberton, along with many other free Black men and women in Henrico County’s “Register of Free Negroes.” Lisa and her team used the microfilm scans of the register to transcribe and index all four volumes. In our continued efforts to shed light on these important resources and encourage their transcription, I asked Lisa if she would share about this experience. We are pleased to share her contribution here.

The Library of Virginia houses all four volumes from Henrico County. Because they already have been transcribed fully, we have chosen not to upload them to our transcription platform, From the Page. We are working with our colleagues in Digital Initiatives and Web Presence to reformat Lisa’s spreadsheets so we can merge this indexed data with the original images in our Virginia Untold database.

–Lydia Neuroth, Virginia Untold Project Manager

Henrico County’s “Register of Free Negroes” encompasses four volumes of 187 pages in total with dates ranging from 1831-1865. The register lists 2,195 names which are not completely unique since some individuals do appear in the register more than once. The Henrico County officials arranged Henrico registers to record information in a tabular format with a few descriptive columns regarding the free individual’s appearance and how their free status was obtained. About ten years ago, we began transcription piecemeal by locating information on specific individuals. I expanded the project to a full transcription, and with the assistance of part-time staff, the entire register’s transcription was completed earlier this spring.

From a historian’s standpoint, some days I was amazed to have this level of detail describing appearances. In this sense, the register is a gold mine since much of this population lived in years prior to photography’s widespread availability. It was even more incredible that we had so much personal information about a group of people of not only a lower socio-economic status, but also a marginalized racial status which set them apart as “free” yet not completely free. There were also days when the details elicited more challenging emotions. Perhaps the most difficult to process upon further reflection was that the register recorded descriptions of marks and scars in areas of a person’s body which were typically covered by mid-19th-century clothing. For females, this was particularly disturbing given that this level of inspection would have been unthinkable for a white woman to endure, yet it was considered acceptable to notate scars of these free Black women and girls. These notations conjured images of enslaved people being inspected prior to being auctioned.

The register presented many avenues for further investigation, one of which was the story of Edward Cornett. Although different than the story of William H. Pemberton, whom the clerk recorded as having a white father, Cornett also had a rather unique status. He was recorded as having a white mother. In total, Henrico’s register noted fourteen free Black individuals whose status was “born of a white woman,” one of whom was Cornett, who registered twice in the 1850s while in his twenties. The 1850 federal census of Henrico County listed Cornett as belonging to a household in which a white woman, Elizabeth Lucas, was recorded as the head. Also in the household were three teenagers – Elizabeth (17), Amanda (12), and Edward (18) Lucas – all indicated with the race “mulatto.”

Another layer of information about this family is contained in the Meadow Farm Sheppard papers (1770-1980) in our Henrico County archives. Dr. John M. Sheppard lived and practiced medicine in the Glen Allen community of Henrico during the antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction eras. His financial medical account books for twenty-nine years of his practice (1845-1874) survive and have been the subject of a more recent, ongoing research project. Alone, these books are a good source of information on a 19th-century country doctor’s practice; but when reexamined through the lens of local history and genealogy, they become a vital source of information about the enslaved community. A few free Black individuals appeared in Dr. Sheppard’s account books, including an account holder by the name of Ned Cornet in 1846. “Ned,” as many might know, is a common nickname for Edward. Ned paid for Dr. Sheppard to treat a child named Amanda. An Amanda Cornet appears later in the account books as an adult patient receiving treatment from Dr. Sheppard in 1864.

Ned Cornet paid for the services of Dr. Sheppard to treat two children, Amanda and Ned.

Dr. Sheppard Medical Account Books, 1845-1874, Henrico County Meadow Farm Museum Collection

Over twenty years later, Amanda Cornet, now an adult, paid for the services of Dr. Sheppard.

Dr. Sheppard Medical Account Books, 1845-1874, Henrico County Meadow Farm Museum Collection

Henrico’s register included one entry for an Amanda Lucas in 1863. The clerk recorded her age as 26 years old, which matches the estimated birth year for the Amanda Lucas in the 1850 census. The register described her as “a bright mulatto woman.” The clerk only recorded, however, that she was born free and did not identify her as having a white mother. There is evidence that Edward Cornett Sr. fathered at least one child, Edward Jr., and possibly the two girls, Amanda and Elizabeth, by Elizabeth Lucas.

The registers also provided insight about individuals who were in the process of being emancipated. I accidentally discovered the story of Caroline Brown through a Facebook post featuring an antebellum house for sale in Columbus, Ohio. It mentioned that Ms. Brown had been born into slavery in Henrico and had been freed. Immediately intrigued, I decided to see what further information I could find. When John D. Brown died in early 1848, he specifically mentioned a Caroline in his will as “his woman,” leaving her a curtained bedstead. He also specified that Caroline and her two children, Edward and Constantia, were to be freed and the money generated from the estate sale be used to relocate them to Ohio. While Brown does not specifically claim the two children as his own, the fact that he mentioned them in his will could indicate that they were his children. By the time of his death, Brown owned twenty-seven other enslaved people belonging to three family groups, according to the will inventory made by his executors. He did not free any of these other enslaved individuals in his will. In fact, he permitted them to be auctioned for the estate sale, which ironically contributed to the funding used to send Caroline and her children to a non-slaveholding state.

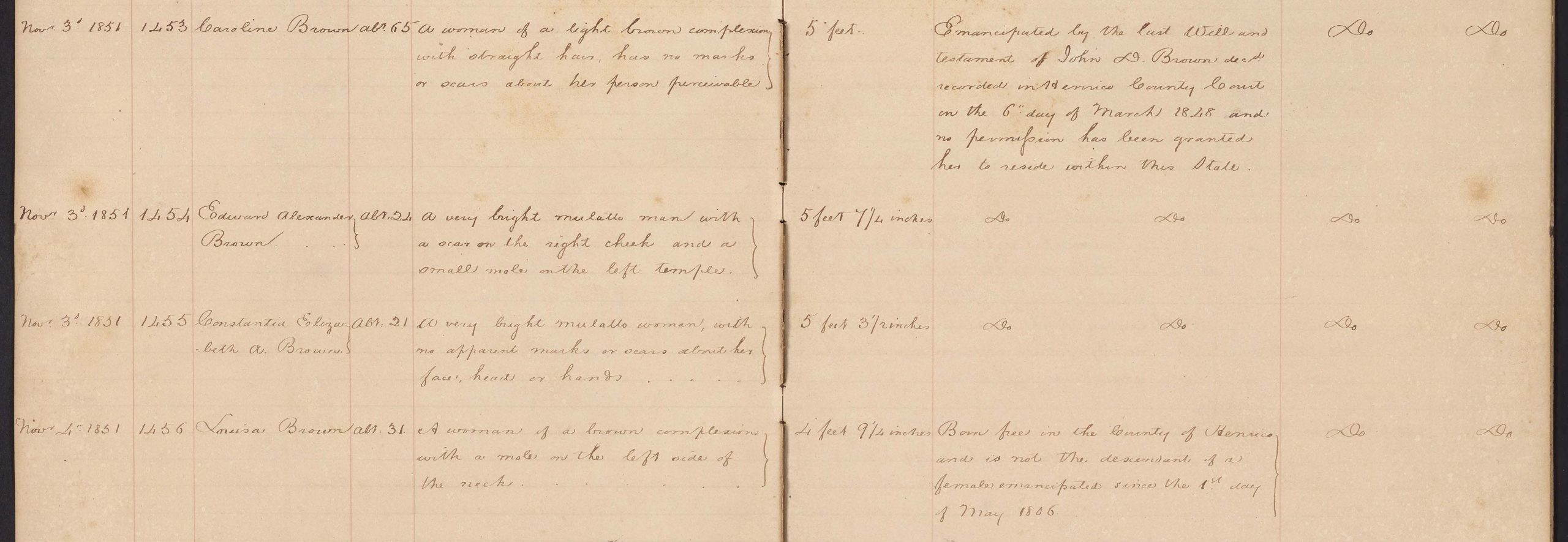

During this process, it was unclear to us what documents might mention the Browns. Would they be documented in the “Register of Free Negroes”? A search of the transcription provided a quick answer – YES! In November 1851, Caroline, Edward, and Constantia still resided in Virginia. Exactly why they remained in the Commonwealth remains a mystery since Brown’s will specifically mentioned that freedom would be granted upon Constantia’s eighteenth birthday. If Constantia’s birth year of 1830 is correct, then she would have turned eighteen in 1848 – the year Brown died. Yet, they did not register in the years 1848-1850. Why? They did register in 1851 and Constantia was recorded as twenty-one years old. In addition, Virginia law required a formerly enslaved person who had been emancipated to petition the General Assembly for permission to remain in the state with their free status. Did they slip through some legal loophole due to a delay? Did it take longer for the estate sale proceeds to be paid? Brown’s executors extended some credit, six to eighteen months, to buyers. Did the executors have to have all reports of debts fully paid and paperwork submitted to the courts before Caroline, Edward, and Constantia would be granted freedom officially? Or was the delay due to executors working to finalize details for land and housing in Ohio?

The register described Caroline Brown as “a woman of a light brown complexion,” but Edward and Constantia were even lighter in skin color. This lends support to the argument that their father may have been a white man.

Henrico County (Va.) Registers of Free Negroes, 1831-1865. Local government records collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

While this emancipation story appears to be straightforward when compiling all the documents – from census, will, and estate papers, to entries in the register – the evidence indicates it was anything but simple. One can only imagine the frustration and anxiety the Browns felt knowing they were free, but not fully free while stuck in Virginia. Perhaps they endured mixed emotions of leaving the familiar, while also feeling eager to welcome a fresh start as fully free individuals and as a family unit.

Even though the transcription is complete, the project is far from finished and there is so much more to learn. One of the more time-consuming aspects will be to match registers of individuals who appeared more than once. We plan to continue to research individuals to learn more about the lives of free Black people in Henrico. Another aspect of the project will include data analysis of various categories ranging from average height, oldest and youngest individuals, and tracking trends in when and how many registered. We will also collect data on aspects such as the movement of individuals in and out of the county and the vocabulary used to describe hair or skin color. These categories could prove useful to compare these registers with other localities to provide a more complete interpretation of the lives of free Black individuals in Virginia.

–Lisa Denton, Recreation Coordinator II, History Programs, Recreation and Parks, Henrico County