Rachel Findley was a mother. She was a grandmother. She was a Virginian. She was also enslaved. The law defined Rachel as property. Because Rachel carried the status of an enslaved woman, this meant that Rachel’s children were also enslaved. Because her children were enslaved, Rachel’s grandchildren were also enslaved. But Rachel knew she was more than what Virginia law defined for her. She rejected the restrictions placed on her freedom and the freedom of her descendants. She knew what rightfully belonged to her and she used the court system to fight for it.

In the early 1770’s, Rachel and other members of her family instituted a suit for their freedom in the General Court at Williamsburg against their owner Thomas Clay of Powhatan County. Freedom suits are lawsuits initiated by enslaved people seeking to gain their freedom. These important record types make up some of the original records we scanned and digitized for Virginia Untold. In their freedom suit, Rachel’s family argued that they were descendants of a woman of “Indian Extraction” and according to Virginia Law Rachel and her family members should be considered free people.1 In May 1773, the court decided in favor of the plaintiffs and granted the Findleys their freedom. Rachel was twenty-three years old.

Before Rachel received word of her victory, a member of the Clay family took Rachel to western Virginia and sold her to a man named John Draper of Wythe County. A deponent for the trial testified to this truth: “…that about the time the sutes [sic] were pending several of the Children decendents [sic] of Indian Mothers were conveyed of by the sons of sd. Henry and William and sold as this Deponent always understood to prevent them from an opportunity of obtaining their freedom.” Rachel was pregnant at the time she was sold, which meant her unborn child would begin its life enslaved. For almost forty years, Rachel lived and worked as enslaved woman in western Virginia never enjoying the freedom that she legally won. Rachel’s family grew in these years. She had more children and her children had children, all of whom were born into slavery.

In the years after Rachel’s exile to western Virginia, other members of her family in Powhatan County (including children she had prior to being sold) successfully won their freedom from the Clay family, and ironically, did so on the basis of the original court decision that granted Rachel her freedom. In June 1813, Rachel, now 63 years old, instituted a suit against John Draper in the County Court of Wythe County seeking to gain the freedom she had won forty years earlier. She once again sued on the grounds that she was “descended in the maternal line from an American Indian woman.” Moreover, she wanted to win the freedom of her descendants as well—freedom they should already have experienced.

Rachel encountered obstacles from the local magistrates hearing her suit. They issued regular continuances that delayed the hearing of the case. They imposed travel restrictions on Rachel and her family members that prevented them from obtaining the testimony of witnesses who lived outside of Wythe County. After two years of being mired in a legal quagmire, Rachel petitioned the Superior Court of Law for Wythe County to have her suit heard by them rather than the County Court. She beseeched the court to grant her request without delay because “your Petitioner has between 30 & 40 descendants, children and grandchildren, the liberties of all of whom depend the determination of said suit, and as your Petitioner is old and very infirm, her living cannot be much longer calculated upon, and should she die previous to the decision, the means of proving their right to freedom would be much lessened.” It was not just Rachel’s freedom at stake—if she died prior to a decision by the court, her children, grandchildren, and all of her descendants would never experience the freedom that rightfully belonged to them. The court consented to Rachel’s petition and the case was moved to the Superior Court of Law for Wythe County in 1815.

The change in venue meant a change in how Rachel’s suit would be adjudicated. In the county court, only the local magistrates heard the case. The local magistrates, likely all white men, were also responsible for delivering a ruling. In the Superior Court of Law, however, Rachel’s case was heard before a jury of her “peers.” But what did the term “peers” mean for Black and multiracial Virginians at this time? Virginia law denied people of color the right to serve on juries. Rachel’s legal counsel now had the improbable task of convincing twelve white males that a sixty-year-old Black enslaved woman should be free.

Additionally, Rachel was unable to call as witnesses members of her family who had received their freedom. A 1773 General Court decision stated that Black individuals could not testify against a white individual. Her pool of witnesses was limited to elderly white people who lived hundreds of miles away in Powhatan County. They were the only ones who could remember Rachel, her family, and her enslaver’s family from when she lived in Powhatan County. Many of her witnesses were too infirm to make the lengthy trip from Powhatan County to Wythe County so her legal counsel had to go to them to receive their testimony. None of them had seen Rachel in decades. They had to recall people and events from nearly fifty years prior.

The court case docket front demonstrates how many times Rachel’s case was continued beginning in September 1816 when the court agreed to a change in venue (three years after Rachel initiated the suit) to May 1820 when she was finally granted her freedom.

Findley, Rachel : Freedom Suit, 1820, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.

Perhaps because of these challenges, Rachel petitioned the General Court in Richmond to have her case moved to the Superior Court of Law in Powhatan County. The General Court agreed to the change in venue in June 1816, and the case was finally placed on the docket in September 1816. However, the trial was delayed for four years by continuances at the request of both the plaintiff and the defendant. A jury was finally sworn in May 1820. They read the proceedings from the Wythe County trial, heard testimony from additional witnesses, and then adjourned to decide a verdict. After three days, the jury reached its verdict. It was only one sentence: “We of the Jury find that the plaintiff is free and not a slave, and we do assess her damages to one penny.”

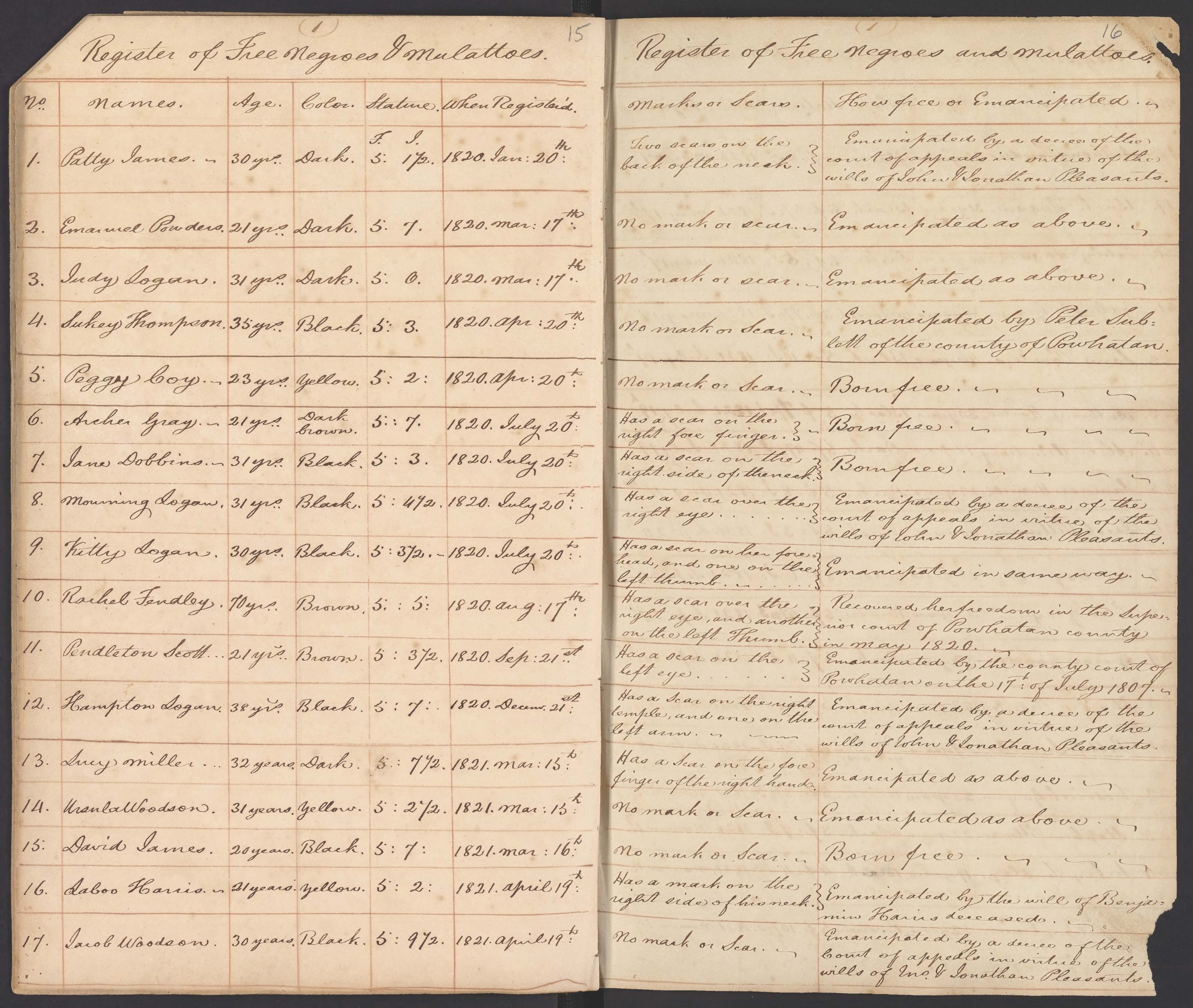

After proving her freedom, Rachel registered herself as a free person in the local Powhatan County court. Her registration paper states that she was of “brown complexion” with a scar over the right eye and another on her left thumb. She was five feet, five inches tall and seventy years old. The registration paper confirmed that she had received her freedom in the “Superior Court of Powhatan County in May 1820.”

The clerk may have sketched out this description of Rachel and her free status before writing a more formal certificate and recording it in the register book. This description was filed in the Powhatan County court papers.

Fendley, Rachel (F, 70): Free Negro Certificate, 1820, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.

This past winter as a part of our two-year NHPRC grant, we scanned and digitized nearly forty registers documenting free people from our collections. The Library has both volumes of Powhatan County’s “Register of Free Negroes and Mulattoes.” Rachel’s name also appears in the latter volume from 1820-1865. The clerk recorded her name, age, height, complexion, marks and scars in his book.

You can currently find the entire register book digitized and available for crowd-sourced indexing on our transcription site, From the Page. By signing up for a free account and joining our transcription efforts, you can participate in making stories like Rachel’s more visible.

Forty-seven years after legally proving her freedom in Powhatan County, Rachel proved her freedom again. The court had decided that all those years of strife and heartache amounted to no more than one cent in damages. But this injustice may not have been at the center of Rachel’s mind. More important for her was likely the fresh hope that the liberties of her children and grandchildren had been ensured.

By Greg Crawford and Lydia Neuroth

The scanning and digitizing of these registers is made possible through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program. An announcement will be made when these records are added to the publicly-accessible digital Virginia Untold project.

Footnotes

- Jane Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia, (Fauquier: Afro-American Historical Association, 1995), 23; https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/negro-womens-children-to-serve-according-to-the-condition-of-the-mother-1662/. The 1662 Act of Assembly declared that children should be bond or free according to the condition of the mother.

Sources

Fendley, Rachel (F, 70): Free Negro Certificate, 1820, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.

Findley, Rachel : Freedom Suit, 1820, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.

Register of Free Negroes and Mulattoes, 1820-1865, Powhatan County Circuit Court Records, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.