T his is the last in a series of four blogs related to the “To Be Sold” exhibit which opens on October 27 at the Library of Virginia. Each post will be based on court cases found in LVA’s Local Records collection and involving human traffickers. These suits provide insight into the motivation of individuals to get into the business of selling forced labor as well as details on how they carried out their operations. Even more remarkably, these records document stories of enslaved individuals purchased in Virginia and taken hundreds of miles away by sea and by land to be sold in the Deep South. Today’s blog focuses on the experiences of enslaved individuals bought and sold by Richard R. Beasley and William H. Wood–experiences conveyed in Lunenburg County Chancery Cause, 1860-026, Christopher Wood, etc. vs. Executor of William H. Wood and Petersburg (Va.) Judgments 1837 May, Hester Jane Carr vs. Richard R. Beasley.

As shared in last week’s blog, Richard R. Beasley and William H. Wood formed a partnership to purchase enslaved me and women in Virginia and sell them for a profit in Mississippi and Louisiana. Following the death of Wood in 1845, Beasley was responsible for administering his estate. Wood’s heirs sued Beasley, accusing him of mismanaging the settlement. Both sides in the suit provided the court with a substantial amount of testimony and exhibits which brought to light the operations of a slave trade business. Through these court documents, we also learn information about the individuals who were trafficked by Beasley and Wood.

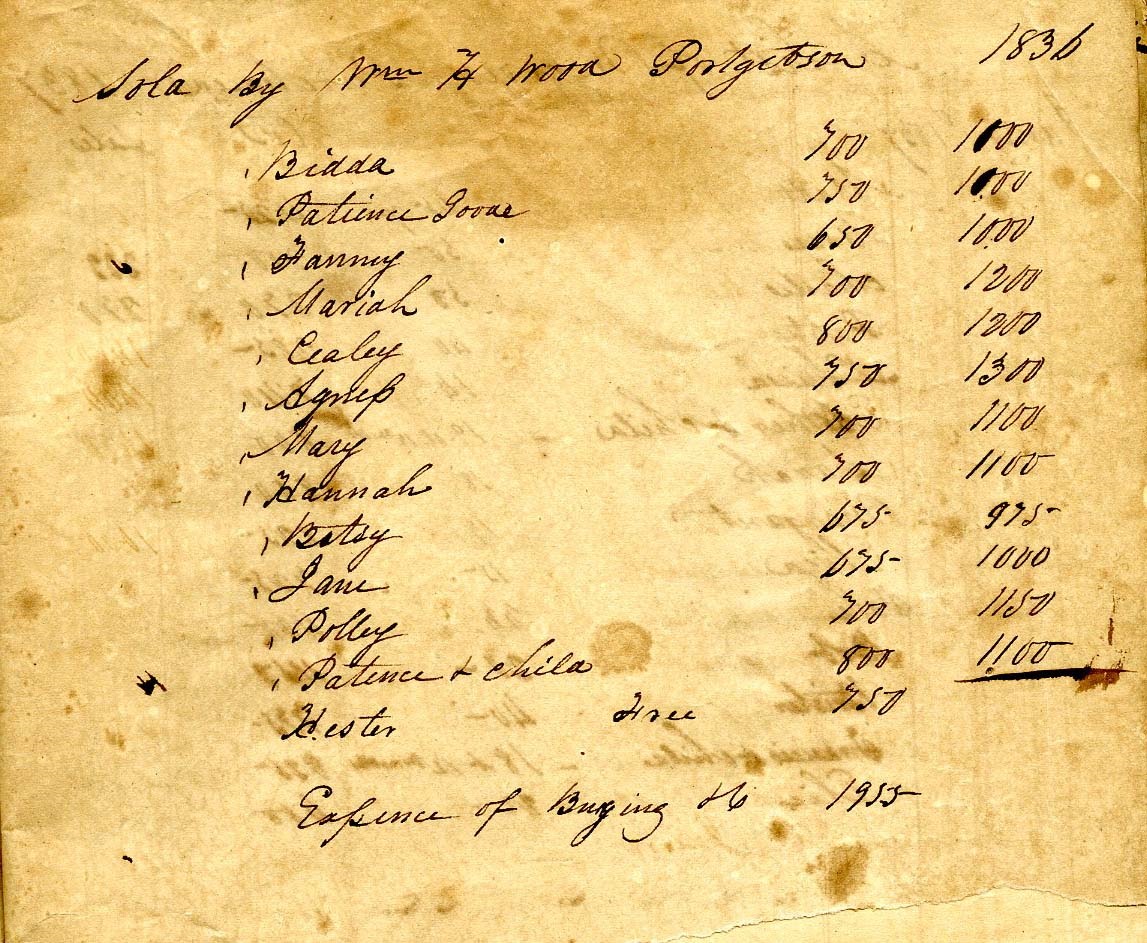

Filed in the suit is an account book dated 1835 to 1851 and used by Beasley and Wood to keep track of the purchase and sale of enslaved individuals during their partnership. The majority of the volume consists of lists of people purchased in Virginia and sold in the Deep South, primarily Mississippi. Some of the lists are titled “Natcheze,” “carried to the South,” or “sold by William H. Wood Port Gibson [Mississippi].” The lists are divided by gender and they include the name of the individual, the price of purchase, and the price of sale. Some lists include ages, occupations, family relationships, and the name or residence of the individual who purchased the enslaved individual. The youngest enslaved child bought and sold was an unnamed one–year-old and the oldest individuals were Moses and Charles, both aged 50. (Between 1830 and 1860, only 10 percent of enslaved people in North America were over 50 years old according to the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History). The vast majority of the men and women sold in the account book were between the ages of 15 and 25. The individuals who purchased the enslaved individuals came from Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, and the city of New Orleans. Numerous purchasers were identified as living on the “Coast.”

The following are a few of the individuals who were bought and sold by Beasley and Wood: Jack, a shoemaker, age 24, was purchased in 1845 by Beasley for $466 and sold in Alabama for $750 [$11,814/$19,015 in 2014 dollars]. Hetty, age 18, was purchased in Virginia in 1840 for $470 and sold in 1841 to a Mr. Simpson of Florida for $700 [$11,121/$16,564]. Baccus and his wife, Jane, purchased for $550 each and sold to William B. Barrow for $750 each [$13,994/$19,015]. Sally, age 28, and her three children, Elsybell, age 7, Francis, age 5, and Plumor, age 1, were purchased for $537 and sold together for $1,040 to a Mr. Gill of Red River [likely Louisiana, $13,614/$26,367].

While reviewing all the names of those purchased and sold by Beasley and Wood, there was one name that stood out. In the 1836 list of enslaved females sold by Wood in Port Gibson, the last name on the list was Hester. She was purchased in Virginia for $750 but unlike the other individuals listed there was no selling price. Also, by her name was written the word “Free.” Towards the end of the account book, I found this notation: “The girl that’s claiming her freedom by the name of Hester Jane is also in the concern if recovered.” I did a search of the Library of Virginia’s finding aids in the Virginia Heritage database and discovered an EAD guide for a freedom suit heard in the Hustings Court of Petersburg styled Hester Jane Carr vs. Richard R. Beasley. The suit details an amazing but tragic story that involved the Beasley and Wood partnership.

Docket, Hester Jane Carr vs. Richard Beasley, 1836.

Petersburg (Va.) Judgments (Freedom Suits), 1824-1852. Local government records collection, Petersburg (City) Court Records. The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

In her petition for freedom, Hester Jane informed the Petersburg court that she was born in 1816 of free parents in Accomack County, Virginia. Her father was Henry Tilghman and her mother was formerly-enslaved but then emancipated by a man named Carr from whom her mother received her surname. Hester Jane’s father moved to New York City, where he died when she was an infant. Her mother continued to live on the Eastern Shore until her death in 1832. Three years later, Hester Jane took a schooner to New York City and found work as a house servant for Dr. James Cockcroft. She even provided the court the doctor’s home address: Forsyth Street, number 24 in Lower Manhattan.

On 18 July 1836, Hester Jane met a woman who claimed to be from Columbus, Georgia, named Nancy Daws or Donald. She wanted Hester Jane to come work for her as a “waiting maid” in Georgia to which Hester Jane agreed. When they reached Baltimore, Maryland, Nancy informed Hester Jane “that they were about to enter a slave holding state (Virginia) in which the immigration of free persons of colour [sic] was prohibited under severe penalties.” In order to avoid arrest, Nancy told Hester Jane “to represent herself” as Nancy’s property to which Hester Jane complied. She posed as an enslaved woman all the way to Petersburg where their journey came to an abrupt end. “(T)o her great horror and dismay, she found that the said Nancy Donald had in violation of every principle of justice and humanity actually sold her to the said [Richard] Beasley as a slave and gone off with the money received from him.” As shown in the Beasley and Wood account book, Nancy sold Hester Jane to Beasley for $750 [$16,134].

With the assistance of a local lawyer named William C. Parker, Hester Jane immediately filed suit in Petersburg for her freedom. Beasley was summoned to appear before the court but refused. Hester Jane was placed in the custody of a local officer of the court, probably in the city jail, while her case was heard by the court. Due to this turn of events, Beasley was unable to have Wood transport Hester Jane to the Deep South along with the other enslaved individuals he had purchased in Virginia. That is the reason for the word “Free” found next to her name in the account book and no selling price. The case was continued with no hearings until March 1837. The court found Beasley not guilty which meant Hester Jane was declared to be his property. Her lawyer immediately filed a repleader claiming the verdict was flawed and requesting the case be heard again, to which the court agreed. The trial came to an end two months later but not by a decision of the court or an acknowledgment by Beasley that Hester Jane was actually a free person. It ended May 1837 with her death, probably in the Petersburg city jail waiting for her case to be heard once more. She was 21 years old.

News of Hester Jane’s plight made its way back to New York City. She was one of many African Americans in New York City who had been “decoyed” or kidnapped by Southerners and sold into slavery. In response, a group of African Americans formed a committee called the New York Committee of Vigilance to generate public awareness about the kidnapping of free persons of color to be sold into slavery. A meeting of the committee in the fall of 1836 was covered by an abolitionist newspaper, the New York Emancipator. It referenced Hester Jane in an article published on 6 October 1836. A newspaper in England, the London Patriot, reprinted the Emancipator’s article a month later making Hester Jane’s story international news.

At a meeting in 1837, the committee wrote a report that provided narrative accounts of free persons from New York, including Hester Jane, who had been kidnapped and sold into slavery. The report contained additional information concerning Hester Jane’s family, her employer in New York, and her trial in Petersburg. They printed correspondence from her lawyer William C. Parker who was attempting to locate Dr. Cockcroft. In the report, there are also affidavits given to the Mayor of Brooklyn by witnesses who knew Hester. “The First Annual Report of the New York Committee of Vigilance” is available online through Google Books.

Christopher Wood, etc. vs. Executor of William H. Wood, 1860-026, is part of the Lunenburg County Chancery Causes and Hester Jane Carr vs. Richard R. Beasley, is part of the Petersburg (Va.) Judgments, 1837 May. Both are available for research at the Library of Virginia. The processing of both collections was made possible through the LVA’s innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP) which seeks to preserve the historic records of Virginia’s circuit courts.

–Greg Crawford, Local Records Program Manager